Image

The state had triple its average number of outbreaks in December, affecting more than 1,500 people. Settings like schools and nursing homes are particularly vulnerable.

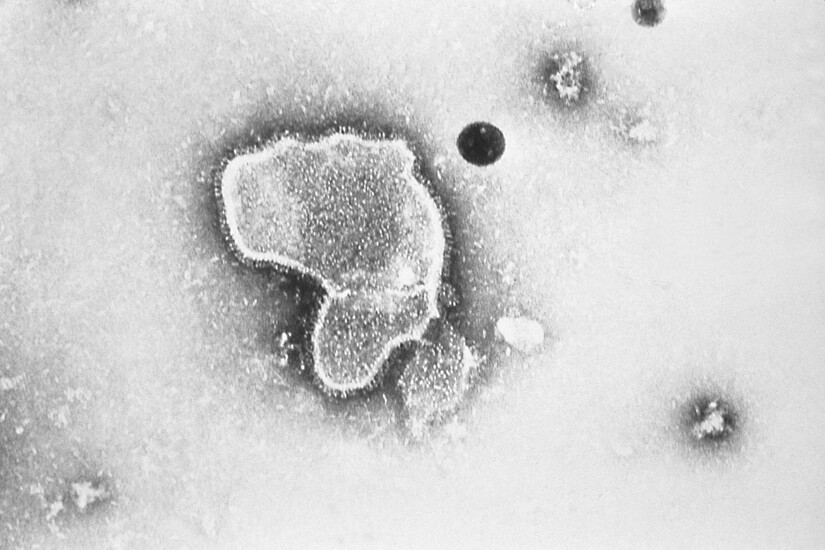

Amid a particularly bad flu season, where respiratory infection cases like coronavirus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are surging in Minnesota, another virus is also making the rounds.

Norovirus, also known colloquially as stomach flu or food poisoning, is seeing some of the highest outbreaks in recent years, spiking to more than three times the normal rate in December. Doctors, state health officials and public health experts are working to get the word out on prevention methods to help stop the spread and limit the strain on emergency rooms across the state.

The highly contagious illness spreads rapidly in crowded settings like schools and nursing homes. It only takes a few norovirus particles to make people sick, so the virus spreads quickly if an infected person vomits or touches surfaces or food after not washing their hands.

Norovirus spikes every five to six years, said Dr. Krishnan Subrahmanian, a pediatrician at Hennepin Healthcare and chief medical officer at Hennepin Health. The main symptoms are diarrhea and vomiting, though people with more severe cases may suffer from a fever or dehydration due to not being able to retain more fluids than they’re losing, he said.

“By virtue of just the fact we’re seeing a lot more norovirus, we’re seeing a lot more kids and elders get to the severe range,” Subrahmanian said. “Severe range of illness, which can require hospitalization, usually is seen in so much diarrhea and vomiting that people can’t keep up with drinking water.”

Norovirus outbreaks were trending below last year’s total through November, according to MDH data. But confirmed and suspected outbreaks increased to 76 in December, representing more than 1,500 individual cases. Those elevated numbers have continued into January, with the state recording 26 outbreaks so far, in a month that usually sees 18 total outbreaks, said Amy Saupe, an epidemiologist in the agency’s Foodborne Diseases Unit.

Saupe said the outbreaks are appearing in settings where people live in close quarters or spend more time in enclosed spaces, where there are more opportunities for the virus to spread quickly. MDH offers toolkits specific to long-term care facilities and schools that include information about the virus and how to report suspected outbreaks.

“That’s why we see it a lot in long-term care facilities, we have a lot of people living in closer contact and sharing food. Same with schools,” she said. “It’s the same reason often people think of things like cruise ships when we talk about norovirus, and also we see it impacting people who are in maybe a transitional housing facility or are currently unhoused and kind of living in close proximity with other people too.”

Melanie Firestone, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health, said a couple factors may be contributing to the unusually high number of norovirus infections.

The way medical and public health officials identify pathogens and outbreaks has been steadily improving over time, she said. And there is more public knowledge and awareness of infectious diseases following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though most people were in close quarters during the pandemic, norovirus cases remained low during those years due to higher awareness of prevention methods like handwashing, she said.

“In the past, with norovirus, people might have called it things like ‘stomach bug’ or ‘vomiting disease,’ but now there’s more of an awareness, both in the media and in the general population, about what is, what it’s called, and what the cause is,” Firestone said. “So better identification of it and better awareness of it makes it more common that we’ll talk about it by name.”

Subrahmanian said the increase in norovirus outbreaks alongside high influenza, coronavirus and RSV cases has led to emergency rooms with long wait times.

People can stop norovirus from spreading by washing their hands with soap for at least 20 seconds and avoiding any food preparation for at least a day or two after displaying symptoms. Health officials also recommended that bleach be used as a disinfectant to clean surfaces, and cooking oysters and shellfish before eating them.

Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, which became popular during the pandemic, are not effective in curbing contamination and stopping the spread, he said.

“This virus, I’ll say, spreads incredibly well. It’s very good at going from person to person, so we really do encourage everyone to wash their hands incredibly well,” Subrahmanian said.

“For example, if you’re helping out a baby or an elder, you’re washing your hands after you do diaper changes, being very careful around food, because this can spread really easily and so we offer that advice because we don’t want one case to lead to a whole household or a whole neighborhood or community being affected.”

SOURCE: Sahan Journal