Image

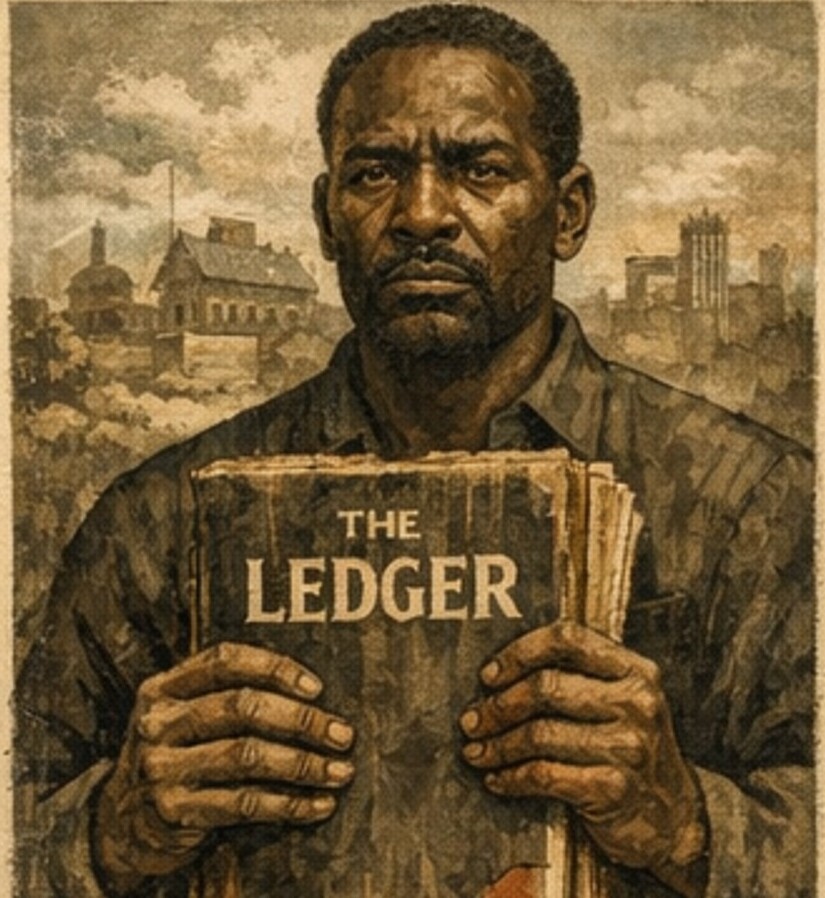

American history contains a repeated insult disguised as analysis.

When poverty appears, it is treated as evidence of deficiency. When wealth is absent, it is treated as evidence that effort was absent. When African Americans are discussed in economic terms, the conversation too often begins at the wrong starting line and then blames the runner for arriving late.

The record tells a harsher truth.

African Americans did not simply face hardship. They faced an economic order engineered to extract their labor, restrict their mobility, deny them capital, and criminalize their attempts at independence. They responded by building survival economies, cooperative systems, and institutional strategies that sustained families and communities even when the nation’s formal economy was designed to discard them.

This is not a story of victimhood. It is a story about accounting.

If the United States wants an honest narrative of prosperity, it must acknowledge what African Americans built, what was taken, and how extraction was repeatedly disguised as policy.

Emancipation ended legal enslavement. It did not end economic captivity.

Millions of formerly enslaved people entered “freedom” without land, cash, tools, or legal protection. They were expected to compete in markets they had been barred from entering and to accumulate wealth in an economy that had already consumed their labor for generations.

In much of the South, new laws and labor practices emerged almost immediately to trap African Americans in dependency. “Black Codes” and vagrancy laws criminalized unemployment and poverty, making economic instability itself a punishable condition.

Freedom was declared. Extraction adapted.

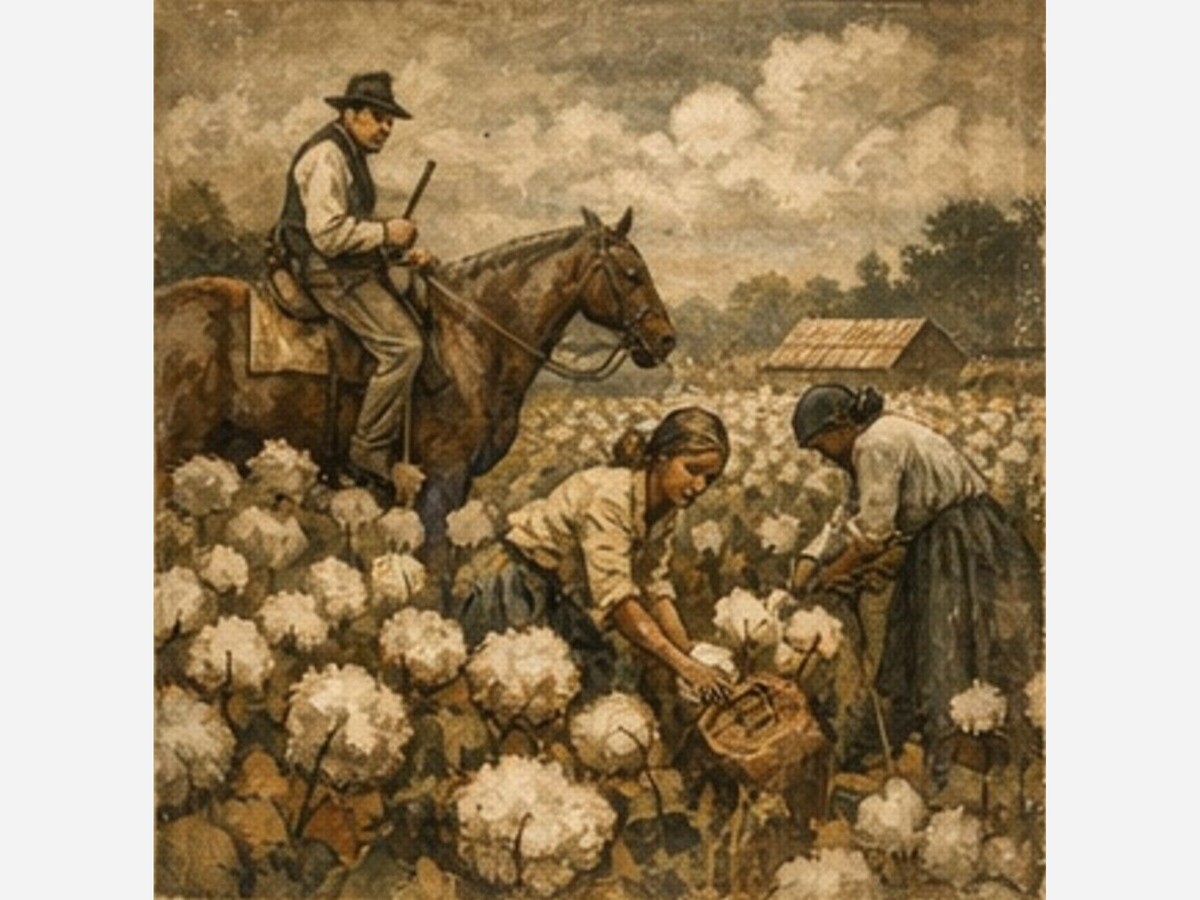

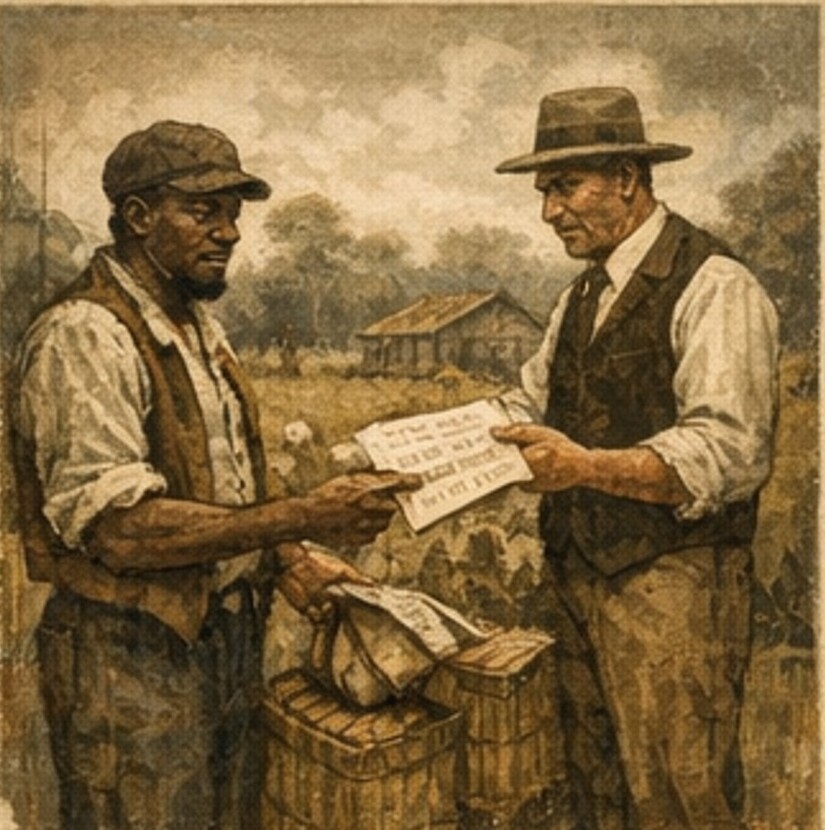

Sharecropping was widely presented as a compromise. Landowners possessed land. African American families possessed labor. On paper, the system promised autonomy. In practice, it often produced a cycle of debt that families could not escape.

Under sharecropping, families paid for land, housing, tools, and seed out of the crop itself, often under terms controlled by the landowner or merchant. Credit was extended at punitive rates. Accounts were opaque. The crop lien system allowed a local economy to function as a private court, where debt could be used to enforce labor discipline.

This was not an accident of bad bookkeeping. It was a model.

It reconstituted coerced labor through contracts and debt, preserving the economic hierarchy of enslavement while claiming to operate under freedom.

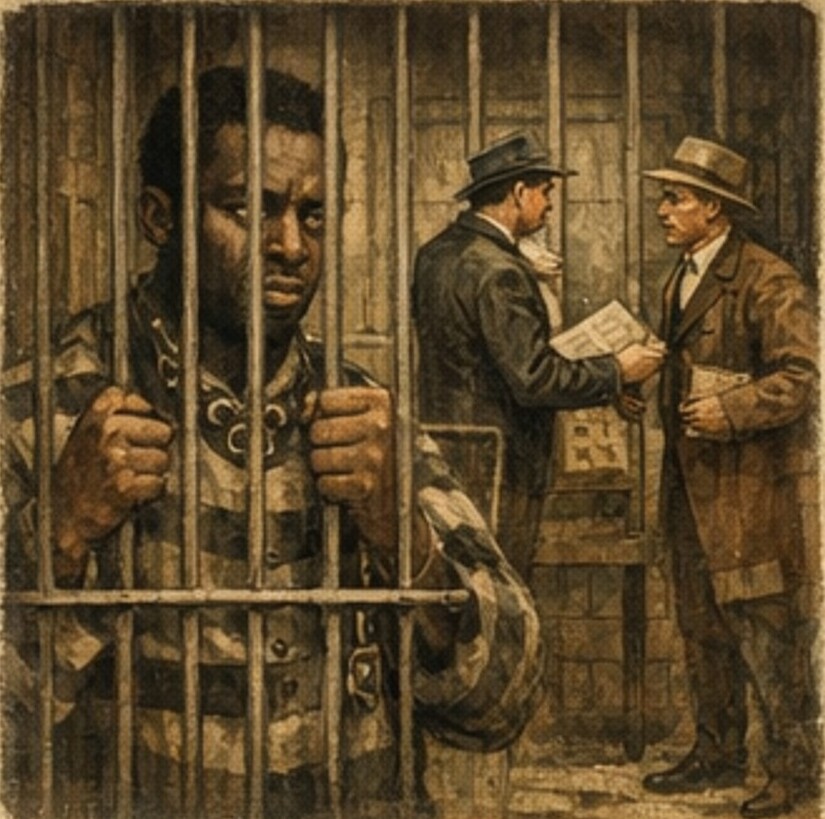

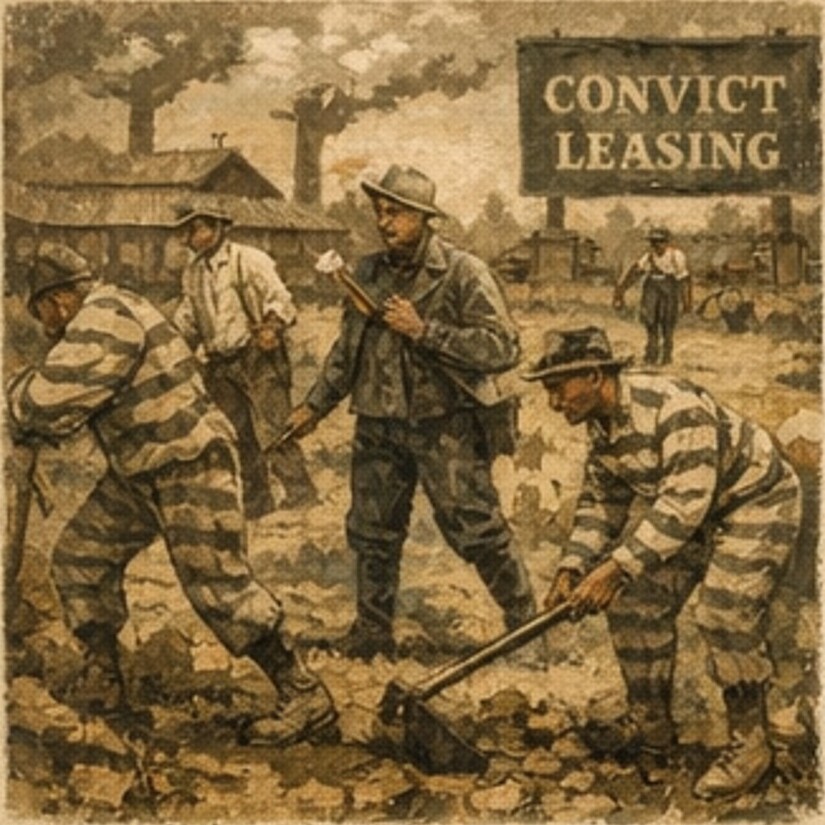

The Thirteenth Amendment prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, with one notorious exception: punishment for crime.

That exception became an economic weapon.

Across the South, legislatures expanded criminal codes and selectively enforced laws against African Americans. Vagrancy, loitering, and minor “offenses” became pathways into jail, and incarceration became a labor supply. States leased incarcerated people to private companies and plantations, generating revenue and restoring coerced labor in a new legal form.

If enslavement was an economic system enforced by violence, convict leasing was an economic system enforced by law and violence together.

This is part of the ledger too.

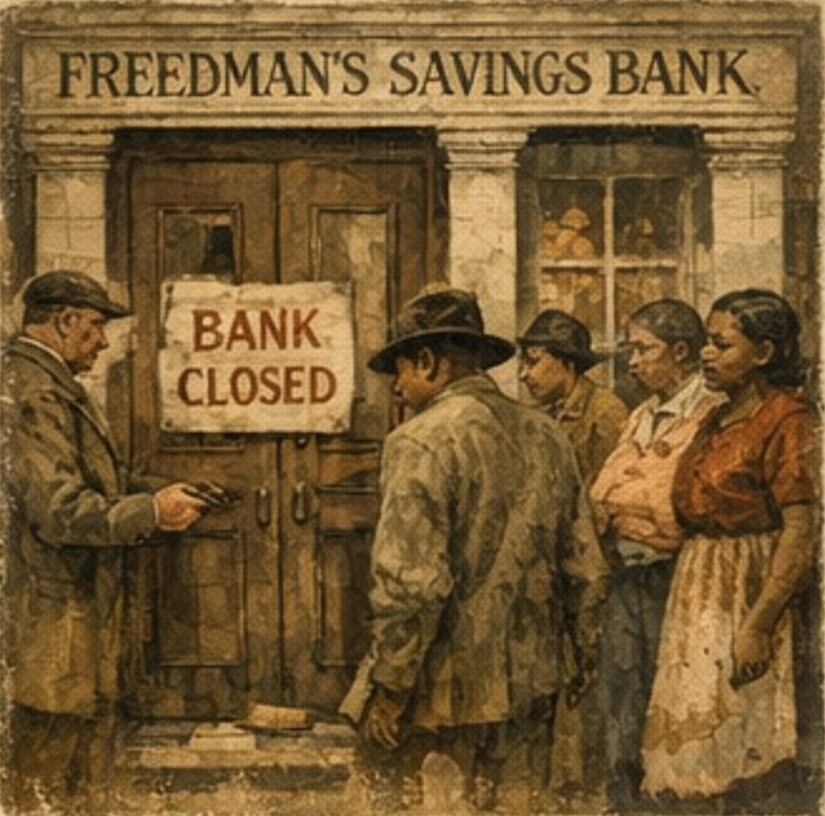

After emancipation, African Americans sought safe places to deposit earnings and build savings. The Freedman’s Savings Bank was created in 1865 with the aim of serving formerly enslaved people. It expanded rapidly, becoming a symbol of economic possibility.

It collapsed in 1874.

Federal sources describe how the Panic of 1873, mismanagement, and investment losses contributed to its failure, draining reserves and devastating depositors.

The human impact is not an abstraction. The collapse represented thousands of families who did what the nation demanded, saved diligently, trusted institutions, and watched those savings evaporate.

It was not merely a financial event. It was a lesson delivered through loss: even “safe” paths could be sabotaged.

In the face of exclusion from formal systems, African Americans built what economists now call informal economies, though the term often hides the dignity of the work.

They created networks of domestic labor, skilled trades, child care, food services, repair services, and mutual credit. They pooled money through churches, fraternal orders, and mutual aid societies. They supported widows, financed burials, paid medical bills, and created emergency funds when public institutions either refused service or offered only humiliation.

These were not side economies. They were community-built infrastructure.

They proved a consistent truth: when a system denies access, people create systems of their own.

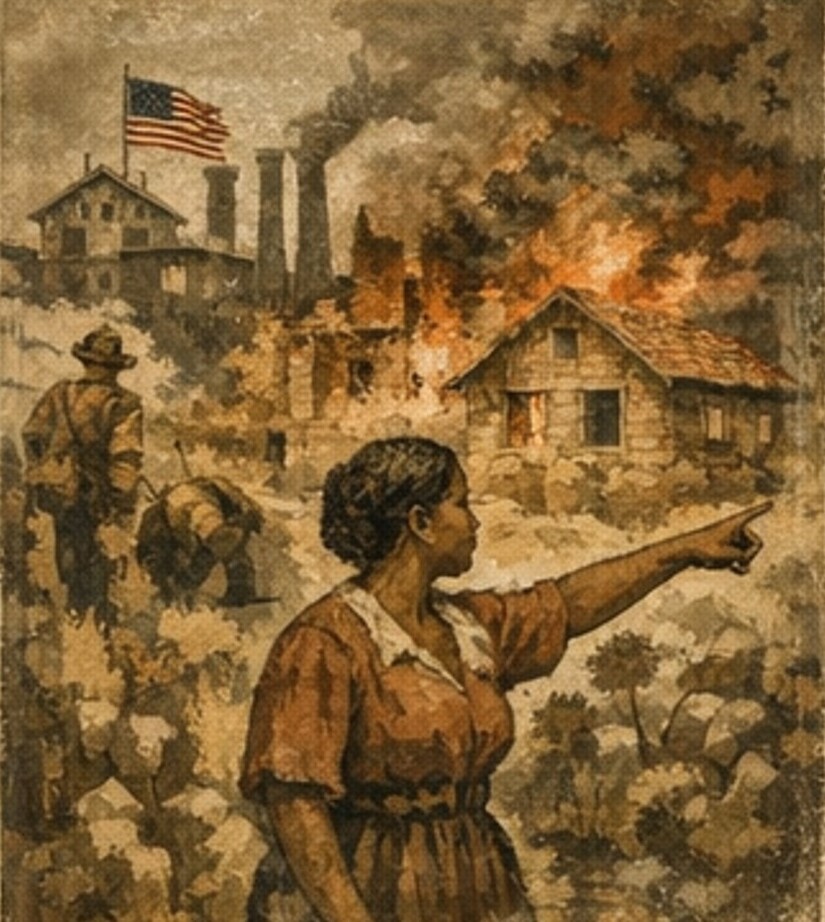

African Americans built businesses in hostile environments. Barbershops, restaurants, beauty salons, tailoring shops, laundries, newspapers, funeral homes, and small retail enterprises became anchors of community life.

But entrepreneurship did not protect them from the central problem. Wealth requires stability. Business requires protection. Both require law to function fairly.

Across the country, African American success often triggered backlash, disinvestment, and violence. A thriving business district could be targeted by policy or terror. Ownership could be stripped by discriminatory lending. Insurance could be denied. Permits could be withheld. Customers could be threatened.

When people ask why intergenerational wealth is uneven, they often ignore that African American wealth was repeatedly treated as temporary.

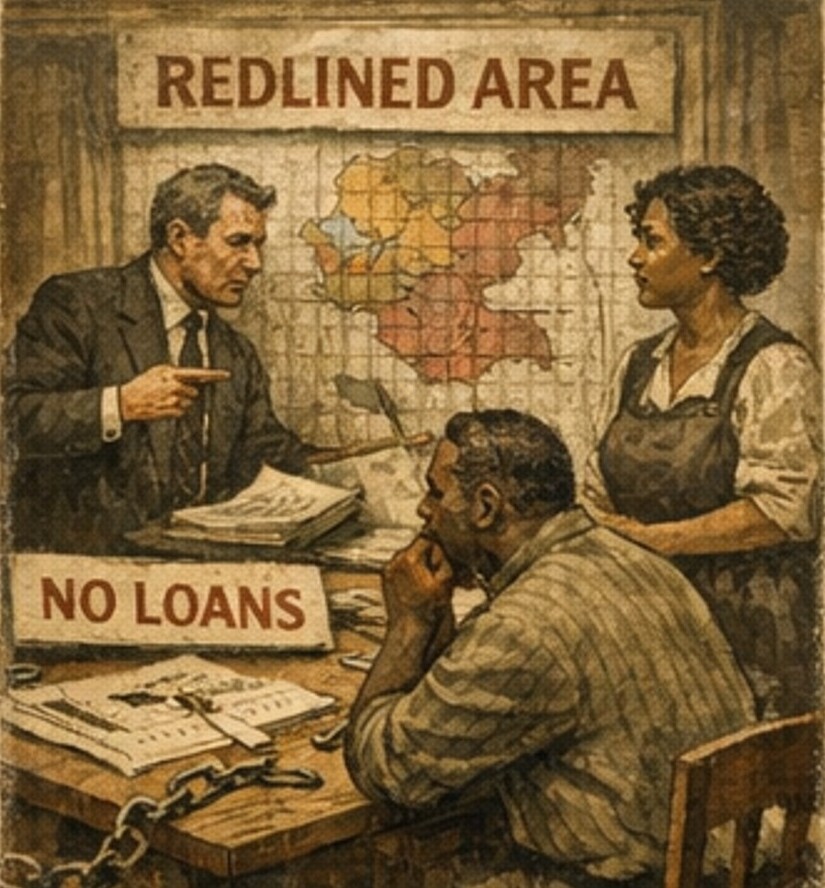

If there is a single arena where the nation’s economic choices become generational, it is housing.

In the twentieth century, federal housing policy helped build the American middle class through expanded mortgage availability. But those benefits were unevenly distributed. Federal policy “institutionalized redlining,” embedding segregation into risk assessments and shaping where capital would flow.

This mattered because homeownership is not only shelter. It is the primary engine of intergenerational wealth for many families.

When African Americans were denied mortgages, steered into segregated neighborhoods, and subjected to disinvestment, the result was not simply exclusion from homes. It was exclusion from the compounding effect of stable assets.

A mortgage is a policy tool that creates future. Denial is also a policy tool.

And the consequences remain visible.

Minnesota is often described as a place where discrimination was less explicit. That framing can itself become an alibi.

Northern and Midwestern states did not need plantation economies to reproduce inequality. Exclusion can be enforced through zoning, lending patterns, employment networks, school boundaries, and the quiet discretion of gatekeepers.

When access to capital is restricted, families build survival strategies. When neighborhoods are segregated, wealth is distributed unevenly by design. When schools are funded through property values, education becomes a downstream consequence of housing policy.

This is how economic harm becomes ordinary. It becomes invisible because it is procedural.

The language of personal responsibility becomes dangerous when it is separated from the record.

African Americans did not fail to build. They built relentlessly.

They built churches that functioned as financial and political institutions. They built schools when education was denied. They built mutual aid systems when insurance was unavailable. They built businesses when employment was restricted. They built newspapers when they were misrepresented. They built savings even when banks failed them.

The question is not whether African Americans worked hard enough to deserve prosperity. The question is why the nation repeatedly redesigned rules to prevent that work from producing the same returns enjoyed elsewhere.

A serious country keeps serious records.

It counts labor and acknowledges theft. It tracks policy and admits intent. It recognizes that inequality is not merely a condition but a product.

The economics of survival should be taught as a central chapter of American economic development, because it reveals how markets behave when freedom is declared but access is denied. It reveals how communities sustain life when the state offers no protection. It reveals how prosperity is manufactured for some and restricted for others.

African Americans built this country through coerced labor, then rebuilt themselves through institution building, then pursued prosperity in a system that repeatedly treated their advancement as a problem to be managed.

That is the record.

The nation’s wealth is not only a story of innovation. It is also a story of extraction.

If we want honesty, we must start where the ledger begins.