Image

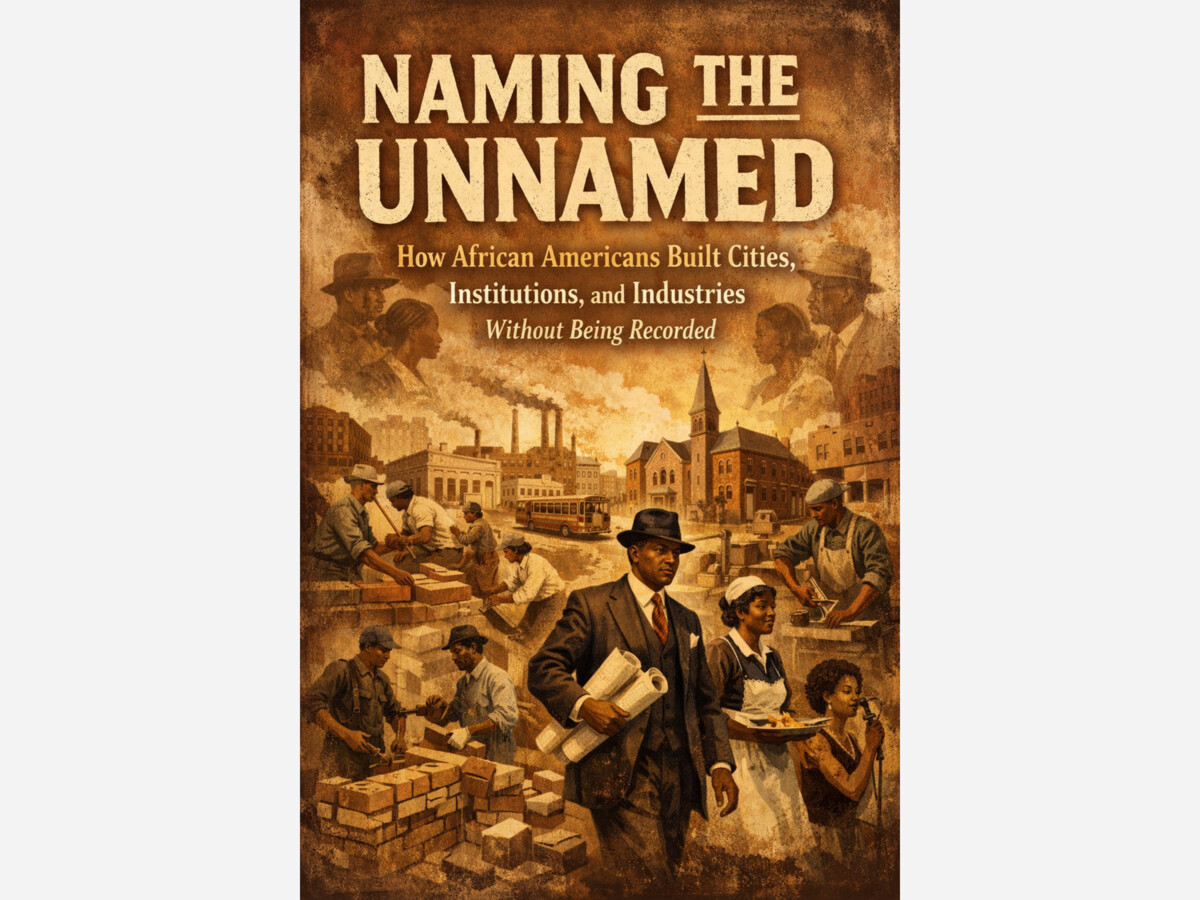

American history is crowded with names. Governors. Industrialists. Generals. Founders. Builders.

It is also defined by absence.

Across cities, towns, campuses, factories, farms, rail lines, and ports, African Americans labored in numbers too large to ignore, yet were rendered small enough to omit. Their work is everywhere. Their names are rarely anywhere. This is not an accident of time or poor record keeping. It is a structural decision about who is deemed worthy of memory.

To name the unnamed is not to add sentiment to history. It is to correct the ledger.

From the earliest days of the republic, African Americans performed essential labor that powered economic growth. They cleared land, built roads, laid rail lines, staffed kitchens, cared for children, forged tools, harvested crops, loaded ships, washed clothes, and maintained homes. Their labor was constant. Their recognition was conditional.

Official records often describe this work without describing the worker. Census rolls counted bodies while erasing biographies. Payrolls listed roles rather than people. Property records credited owners rather than builders. When African Americans appear, they are often reduced to descriptors such as servant, hand, laborer, or help.

The work was visible. The worker was made invisible.

This pattern did not end with enslavement. After emancipation, African Americans continued to build towns and institutions while being excluded from the narratives those places told about themselves.

Urban growth across the United States relied heavily on African American labor. Construction, sanitation, transportation, domestic service, and food systems depended on people whose names rarely entered municipal histories.

When cities celebrate their origins, they often begin with a founding date, a charter, or a prominent settler. The labor that transformed land into livable space is treated as background noise. Streets appear without builders. Neighborhoods emerge without hands. Infrastructure seems to construct itself.

This framing is not neutral. It reinforces the idea that progress is driven by vision alone, detached from labor, and that labor can be absorbed without acknowledgment.

African Americans built cities that did not claim them.

Universities, hospitals, churches, government buildings, and commercial districts relied on African American labor at every stage of development. They cooked meals, cleaned halls, maintained grounds, transported materials, and supported daily operations.

These institutions often celebrate benefactors and administrators while omitting those who made the institutions functional. Buildings are named after donors. Rarely after workers.

Even when African Americans were skilled artisans, craftsmen, or supervisors, their roles were minimized. Skill was acknowledged without status. Contribution was accepted without belonging.

The unnamed were essential. They were never central.

The absence of names is often explained as a limitation of the era. Records were incomplete. Documentation was inconsistent. Memory fades.

This explanation collapses under scrutiny.

When institutions wanted to record ownership, they did so meticulously. When they wanted to track profit, they kept ledgers. When they wanted to enforce law, they documented infractions with precision.

The failure to record African American lives reflects priority, not capacity.

Naming confers legitimacy. To remain unnamed is to remain disposable. Erasure protected those in power from accountability and insulated institutions from claims of obligation.

Erasure is not merely symbolic. It has material consequences.

When African American labor is excluded from the historical record, it becomes easier to argue that inequality lacks precedent. It becomes easier to deny responsibility. It becomes easier to frame disparities as recent or self-generated.

The unnamed are denied inheritance in memory. Their descendants are denied proof of contribution. Communities are denied continuity.

This absence shapes policy debates in the present. When African Americans are portrayed as late arrivals or marginal contributors, claims for repair and redress are treated as demands rather than acknowledgments of debt.

African Americans did not accept erasure passively.

They preserved names through oral history, church records, family Bibles, newspapers, and mutual aid documents. These parallel archives recorded births, deaths, marriages, migrations, and achievements that official histories ignored.

The act of naming became resistance.

Church rolls listed members with care. Newspapers published announcements and obituaries. Families passed down stories when public recognition was denied. These records form an alternative historical infrastructure that persists despite neglect.

The challenge has never been a lack of evidence. It has been a lack of institutional will to treat that evidence as authoritative.

Minnesota reflects the national pattern with particular clarity.

African Americans were present before statehood. They labored in military posts, river trade, agriculture, and domestic service. They helped sustain early settlements and emerging towns.

Yet Minnesota’s self-narrative often begins elsewhere. It emphasizes neutrality, progress, and moral alignment while minimizing the labor and lives of African Americans who made that progress possible.

Local histories list pioneers without listing workers. Economic development is credited upward. Labor remains unnamed.

Silence here is not absence. It is curation.

To name the unnamed is not to reopen old wounds. It is to acknowledge existing ones.

History that excludes labor distorts reality. Democracy that refuses to name its builders undermines itself. A society that benefits from work it will not credit cannot claim moral coherence.

Naming is not about guilt. It is about accuracy.

It is about understanding who built what, who sustained whom, and who was denied recognition while being indispensable.

The unnamed were not marginal. They were foundational.

They built cities that celebrate themselves without them. They sustained institutions that forget them. They labored in economies that profited from their silence.

To name them now is not to revise history. It is to complete it.

The record is not finished because the work was not finished. It is unfinished because acknowledgment was withheld.

This series exists to restore what was removed.

Names matter because people matter.

Labor matters because democracy depends on it.

Memory matters because governance flows from what a society chooses to remember.

The unnamed are still here, in the streets we walk, the buildings we enter, and the systems we inherit.

The work now is to say so, clearly and permanently.