Image

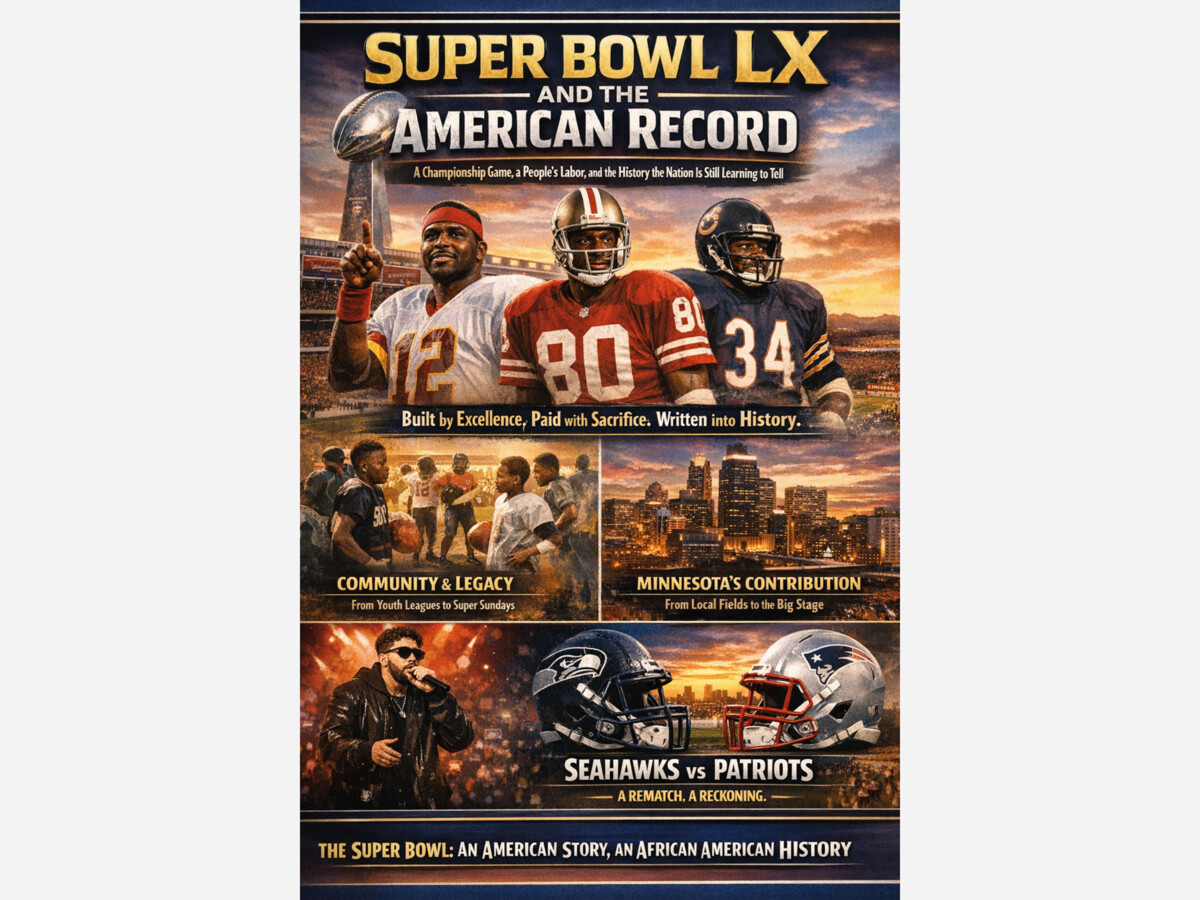

On Sunday, February 8, 2026, the United States will pause once again before a familiar spectacle. The sixty-th championship of the National Football League will unfold beneath the California sky at Levi’s Stadium, ten years after the league last returned to the San Francisco Bay Area. The event will be framed as entertainment, competition, and tradition. It will be packaged as a celebration.

But Super Bowl LX arrives carrying more than ceremony.

It arrives during African American History Month, a period not intended for nostalgia, but for truth telling. It arrives at a moment when professional football stands as the most influential cultural institution in American life outside government itself. It arrives as a mirror of who has built this nation’s most profitable sport, who has borne its costs, and who has too often been written into footnotes rather than chapters.

This editorial is written for the record.

Because the Super Bowl did not simply emerge as a national ritual. It was constructed, sustained, and transformed by labor, innovation, sacrifice, and imagination rooted deeply in African American experience.

The Super Bowl is frequently described as a game. In practice, it functions as infrastructure.

It is a cultural system that binds households, markets, media, music, fashion, language, and civic identity. It is a national moment in which tens of millions participate simultaneously, not because they are told to, but because they feel compelled to.

That compulsion did not happen by accident.

From its earliest decades, professional football relied on athletes of African descent not simply to fill rosters, but to expand the sport’s limits. Speed, vision, physical courage, strategic intelligence, and emotional resilience reshaped what football could look like, how it could feel, and how it could command attention.

Without that transformation, there is no Super Bowl as we know it.

The Super Bowl’s defining performances are inseparable from African American excellence.

Long before the championship became a billion-dollar broadcast, players of African descent elevated football from regional entertainment to national obsession. They did so while navigating racial barriers that restricted leadership opportunities, compressed career longevity, and denied full recognition even as records fell.

The record book tells part of the story.

Jerry Rice remains the standard by which greatness is measured, not because he played long, but because he redefined precision and preparation. Walter Payton carried the ball and carried dignity, embodying excellence that transcended the field. Doug Williams, by leading Washington to victory in Super Bowl XXII, did more than win a title. He shattered a narrative that had insisted leadership at football’s highest level was racially predetermined.

These were not isolated moments. They were structural interventions.

Every generation of Super Bowl competition has depended on African American innovation, from defensive schemes to offensive tempo, from physical conditioning to expressive freedom that eventually reshaped the league’s public image.

Yet for much of that history, access to ownership, front offices, and narrative control remained restricted. Excellence was welcomed. Authority was rationed.

In communities of African descent across the United States, football has never been simply recreation. It has been aspiration, discipline, refuge, and risk.

For many families, the Super Bowl represents the possibility of generational stability earned through singular talent and relentless work. For others, it represents the cost of bodies worn down before their time, long after television cameras turn away. The same game that creates opportunity can also extract silently.

Community organizations, churches, and schools have built systems around football to translate athletic success into educational access and leadership development. Youth leagues became pathways. High school programs became anchors. College scholarships became lifelines.

The Super Bowl is the apex of that ecosystem, but it is not the beginning.

To celebrate the championship honestly during African American History Month requires acknowledging that the spectacle rests on community investment that rarely receives equal return.

Minnesota is not typically framed as a Super Bowl epicenter. That omission distorts the record.

Across Minneapolis, St. Paul, and surrounding communities, Minnesotans of African descent have contributed talent, leadership, and cultural influence that extends well beyond state borders. From high school fields to collegiate programs, from coaching trees to training staffs, Minnesota has served as a quiet incubator for excellence that surfaces on the sport’s largest stage.

The Minnesota Vikings, despite the absence of a championship banner, have played a significant role in shaping the league’s talent pipeline. Players developed within Minnesota systems have gone on to anchor Super Bowl rosters elsewhere. Coaches and coordinators trained in the state have carried principles of adaptability and discipline into championship environments.

Beyond the professional level, Minnesota’s African American communities have sustained football as a civic institution. Friday nights under lights. Saturdays in college stadiums. Sundays in living rooms and community centers. These rituals are not passive. They are instructional, intergenerational, and formative.

When Super Bowl LX takes place, Minnesota’s contribution is present whether it is named or not.

This editorial names it.

The sixty-th Super Bowl arrives as a symbolic hinge.

Anniversaries of this scale invite reflection not only on achievement, but on authorship. Who built this institution. Who sustained it. Who paid its costs. Who benefited most.

The matchup itself carries historical weight. The Seattle Seahawks and the New England Patriots return to a stage that once defined an era. This is not simply a rematch. It is a reckoning with memory, legacy, and unfinished business.

But beyond the field, Super Bowl LX signals a broader transition. The league’s stars are younger. Its audience is more global. Its cultural language is increasingly shaped by African American expression that is no longer peripheral, but central.

The halftime performance, led by Bad Bunny, reflects a league acknowledging that cultural dominance does not require translation. This shift parallels changes long driven by African American influence in music, fashion, and public expression associated with football culture.

Recognition, however, is not resolution.

There are still no African American majority owners in the NFL. Leadership pipelines remain uneven. Decision-making authority lags behind on-field contribution. These realities sit beneath the celebration, unresolved.

Super Bowl LX does not correct these imbalances. It exposes them.

African American History Month is not a ceremonial backdrop. It is a mandate to resist simplification.

It asks the nation to celebrate achievement without erasing struggle. To honor excellence without ignoring extraction. To tell stories fully, even when they complicate comfort.

The Super Bowl offers a powerful lens for that work because it concentrates American values into a single event. Competition. Spectacle. Profit. Identity. Belonging.

African American athletes did not merely participate in this system. They transformed it. They expanded its reach. They gave it rhythm, credibility, and global relevance.

To celebrate Super Bowl LX honestly during this month is to insist that the record reflect that truth without qualification.

Years from now, historians will look back on Super Bowl LX not primarily for its final score, but for what it represented.

They will see a league at the height of its power. They will see a nation negotiating identity through sport. They will see a cultural institution shaped decisively by African American labor, even as structural equity remained incomplete.

They will ask whether the nation understood what it was watching.

This editorial exists so the answer can be yes.

To Minnesotans, especially Minnesotans of African descent, Super Bowl LX is not distant. It is connected. It reflects the labor of communities that have built excellence often without national recognition. It reflects the quiet pride of contribution without applause. It reflects resilience that does not require permission.

To the nation, Super Bowl LX offers a moment to widen the lens. To see the championship not only as entertainment, but as evidence. Evidence of who built the game. Evidence of who sustained it. Evidence of whose stories deserve full chapters.

African American History Month reminds us that history does not write itself. It is written by those who insist on accuracy when celebration threatens to flatten truth.

When the confetti falls and the broadcast ends, Super Bowl LX will enter the archive.

What follows is a choice.

Either the nation remembers only the spectacle, or it remembers the people.

This editorial chooses the people.

Because the Super Bowl is not just a game.

It is a record of American labor.

And African American history is written all over it.