Image

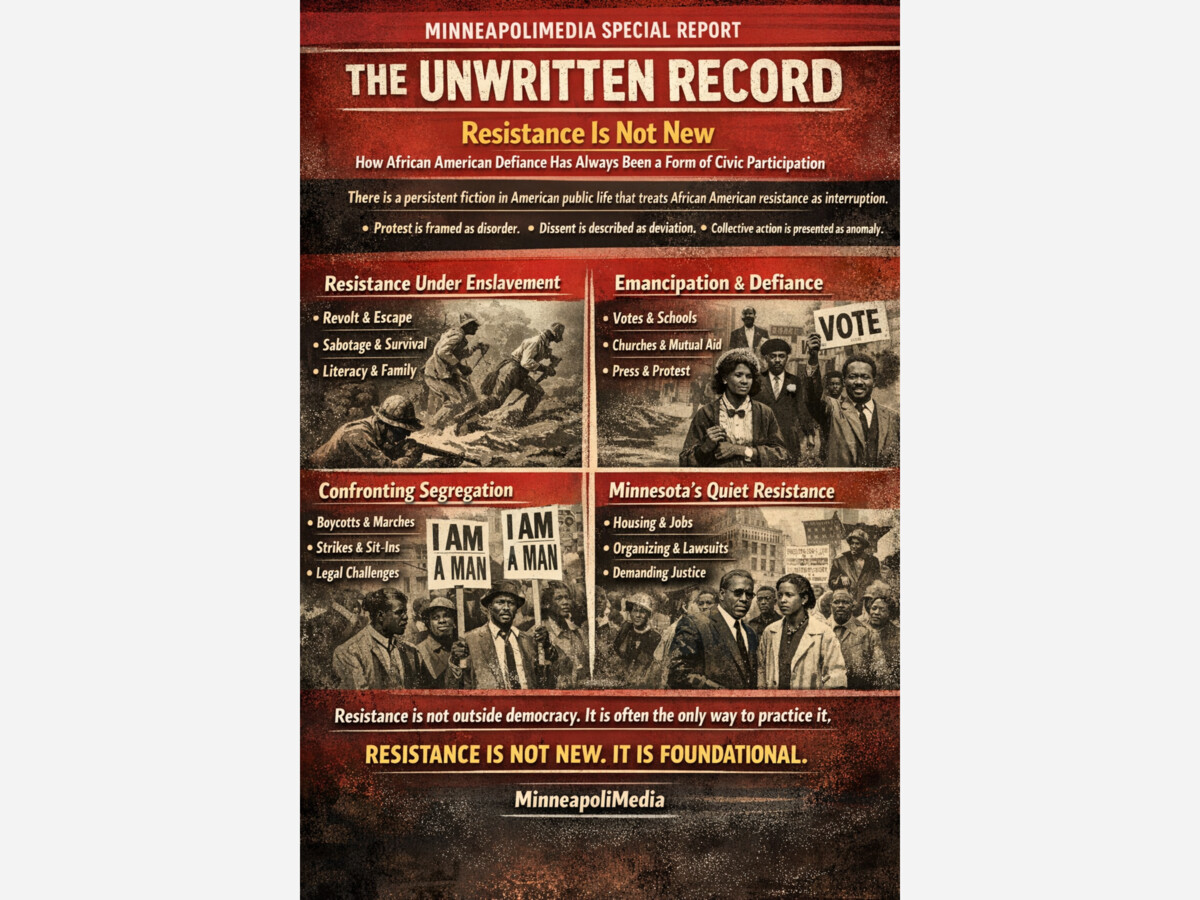

There is a persistent fiction in American public life that treats African American resistance as interruption.

Protest is framed as disorder. Dissent is described as deviation. Collective action is presented as something that appears suddenly, without lineage, and without legitimacy. This framing allows power to treat resistance as anomaly rather than inheritance.

The historical record tells a different story.

African American resistance did not emerge as reaction alone. It developed as practice. From enslavement through emancipation and into the present, resistance functioned as a sustained form of civic participation in a nation that repeatedly denied African Americans lawful means of redress.

Resistance was not outside democracy. It was often the only way to practice it.

Enslavement did not produce submission. It produced strategy.

African Americans resisted through escape, sabotage, work slowdowns, literacy, spiritual practice, and collective planning. Revolts and conspiracies were only the most visible expressions. Daily acts of refusal, preservation, and mutual protection formed a quieter but equally consequential resistance culture.

To learn to read when literacy was criminalized was resistance.

To maintain family ties under forced separation was resistance.

To pass down language, memory, and skill was resistance.

These actions challenged a system that relied not only on labor, but on psychological domination. Resistance disrupted that domination at every scale.

After emancipation, resistance did not disappear. It reorganized.

African Americans immediately pursued voting, education, land ownership, and legal standing. When those efforts were met with violence and exclusion, resistance took institutional form.

Churches became organizing centers. Schools became political spaces. Mutual aid societies became economic shields. Newspapers became instruments of critique and coordination.

Resistance moved from the plantation to the public square.

This was not chaos. It was civic response to exclusion.

As Reconstruction receded, new systems of control emerged. Black Codes, segregation laws, voter suppression, and racial terror narrowed lawful avenues for participation. Courts often refused protection. Law enforcement frequently enforced exclusion rather than rights.

Under these conditions, resistance became necessary rather than optional.

Boycotts, strikes, marches, and legal challenges were not signs of impatience. They were evidence of patience exhausted by denial. When the state fails to respond to petition, resistance becomes petition by other means.

This pattern is consistent across American history.

Minnesota’s reputation for restraint often obscures its own history of African American resistance.

African Americans in Minnesota challenged exclusion in housing, employment, education, and public accommodation through lawsuits, organizing, and protest. They formed civic organizations, demanded fair treatment, and documented discrimination even when public acknowledgment was slow or absent.

Resistance here often took quieter forms, shaped by local culture and demographic realities. But it was no less deliberate.

Silence should not be mistaken for consent.

Restraint should not be mistaken for passivity.

The civil rights movement is often treated as a beginning. It was, in fact, a continuation.

Sit-ins, boycotts, and marches drew on strategies refined over generations. Organizers understood the power of economic pressure, public visibility, and moral argument because these tools had been tested repeatedly.

The movement’s effectiveness lay not only in courage, but in preparation. Resistance had already been practiced in churches, schools, and community organizations long before it reached national attention.

To frame the movement as sudden is to misunderstand its depth.

Throughout American history, African American resistance has often been reclassified as criminality.

Laws have been used to suppress protest, surveil organizers, and punish collective action. This reclassification allows the state to dismiss grievances without addressing their substance.

By criminalizing resistance, power avoids accountability.

Yet the persistence of resistance reveals something else. Even when punished, it continues. Even when ignored, it adapts.

Resistance requires organization, discipline, communication, and strategic thinking. These are democratic skills.

African Americans have repeatedly demonstrated these competencies in environments that denied them formal political power. Resistance became a parallel civic arena where leadership was trained, alliances were built, and policy demands were articulated.

The claim that resistance undermines democracy ignores the reality that democracy often expanded because resistance forced it to.

Acknowledging resistance as civic participation complicates comfortable narratives.

It challenges the idea that rights were granted voluntarily rather than demanded. It reveals that order was often preserved at the expense of justice. It exposes the limits of legal channels when power refuses to listen.

Minimizing resistance allows institutions to celebrate progress without examining the pressure that produced it.

Contemporary protests are frequently framed as unprecedented. They are not.

They reflect a long tradition of organized response to exclusion, violence, and neglect. They draw on inherited strategies shaped by earlier struggles. They emerge not from novelty, but from continuity.

When resistance appears, it signals unresolved conflict, not sudden agitation.

Resistance is not a footnote. It is a throughline.

African Americans did not wait quietly for democracy to mature. They challenged it to become what it claimed to be. When denied access, they built alternatives. When ignored, they made themselves unavoidable.

This history matters because it reframes protest not as disruption, but as participation.

A democracy that refuses to recognize resistance as civic engagement misunderstands its own development.

The American record is incomplete without acknowledging that many of its expansions were forced open by those it excluded.

Resistance is not new.

It is foundational.