Image

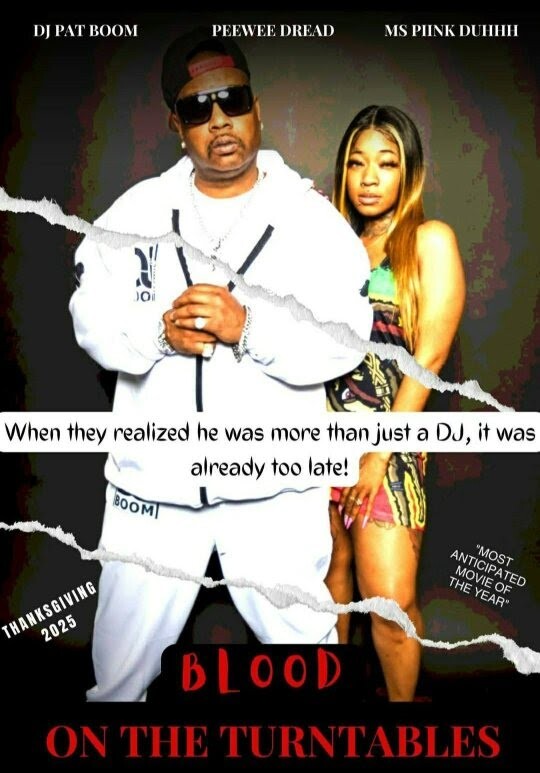

In March, a trailer for a movie appeared online in Minnesota.

There was only one problem. The movie did not yet exist.

“We promoted the movie in March when there was no movie yet,” DJ Pat Boom says now, laughing with the kind of disbelief that only hindsight allows. “The movie was like two percent done.”

There was no studio backing the announcement. No funding round. No distribution deal waiting quietly behind the scenes. There was only a decision, made instinctively, to speak something into existence before it could be fully proven.

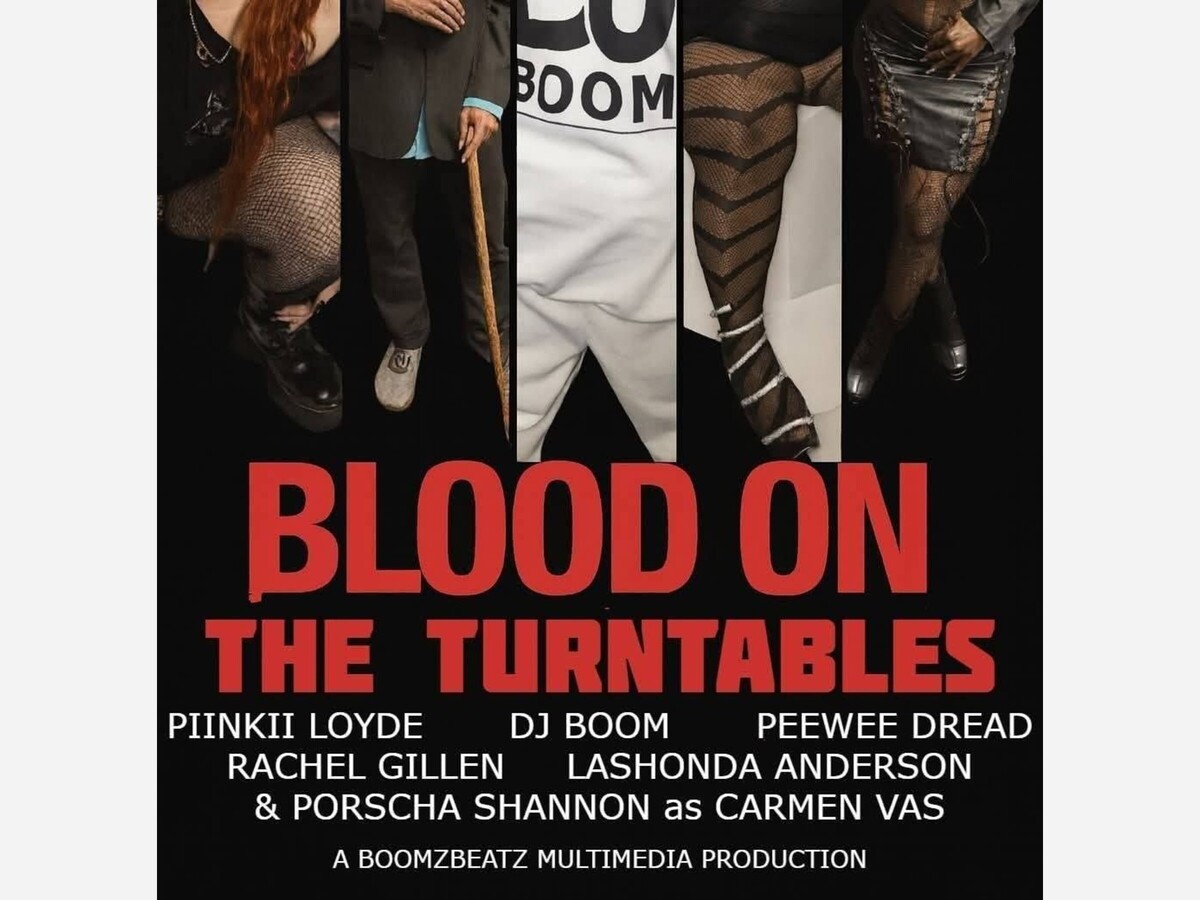

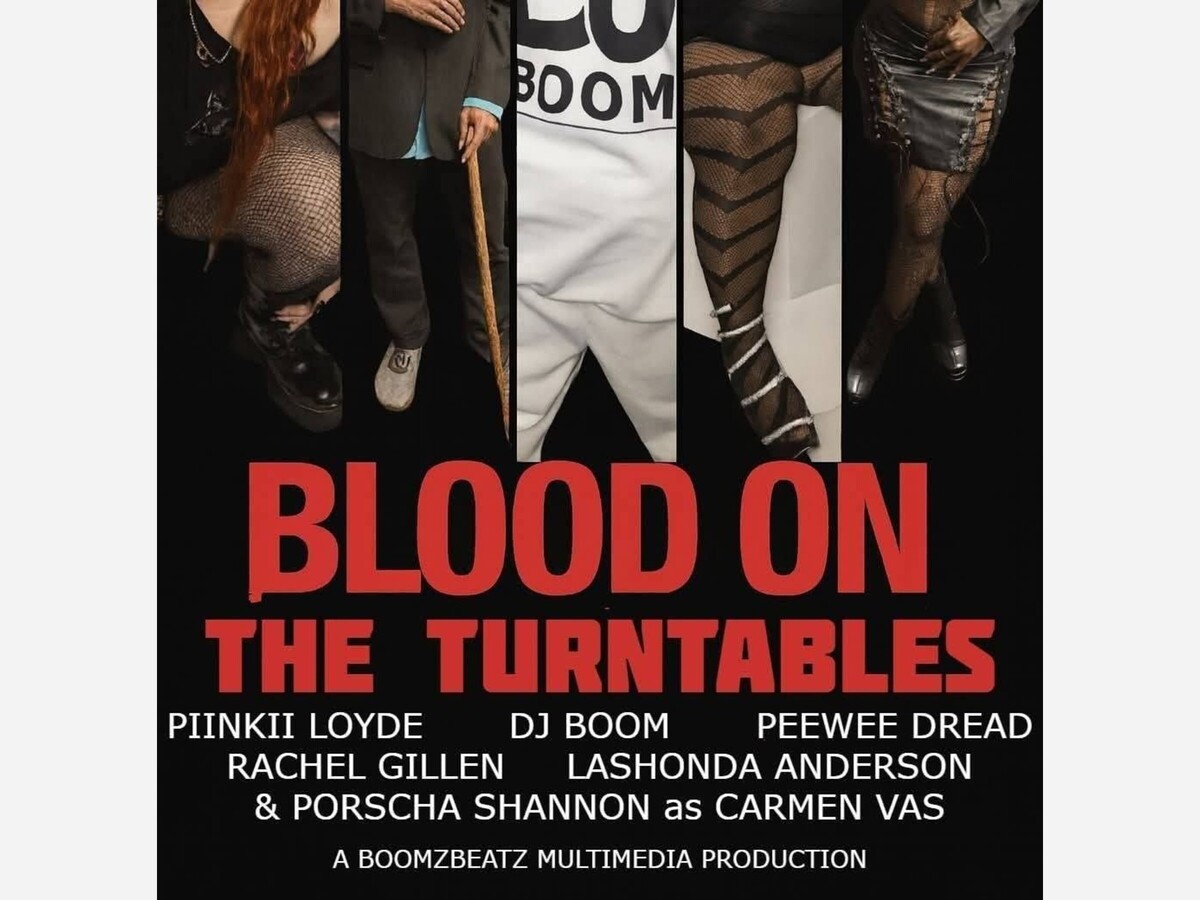

That decision bold, risky, and profoundly independent would come to define Blood On The Turntables, a Minnesota born film created not through institutional support but through trust, grief, and community resolve. Produced under BoomzBeatz Multimedia, the project unfolded with no traditional budget, no industry safety net, and no guarantee that the film would ever be completed.

What it did have was people.

“Everyone I asked said yes,” DJ Boom says. “Nobody told me no.”

That chorus of yeses became the currency that replaced money. Each agreement carried a quiet faith that something meaningful was being built, even if the blueprint was still forming.

For DJ Boom, the film is inseparable from grief. At the end of Blood On The Turntables, as the final images fade and the credits roll, a dedication appears. Dominic Walker. His son.

“He’s the reason for BoomzBeatz. He’s the reason for the channel,” Boom says. “Everything we should have been doing together, I’m doing for both of us now.”

The loss of his son in 2022 reshaped not only his life but his creative urgency. The film did not emerge as an escape from grief but as a vessel for it. Each late night, each rescheduled shoot, each moment of exhaustion carried the weight of a promise being kept.

That emotional gravity did not belong to Boom alone. It quietly shaped the tone of the entire production.

“This wasn’t just acting,” says Rachel Marie Gillen, who served as both cast member and key creative collaborator. “This was personal.”

Gillen felt the project absorb the memory of those lost along the way. Her own grief is also present in the film, which honors her close friends Sandy and Scott, early supporters of BoomzBeatz whose lives were cut short in a tragic accident.

“We always go hard for Dominic,” Gillen says. “And for the people we’ve lost. This film holds that.”

In a production without money to motivate participation, meaning became the binding force. People showed up not for checks but for purpose.

Blood On The Turntables explores the darker undercurrents of the music industry. Ambition. Corruption. Loyalty tested by power and proximity. Yet the film resists becoming didactic.

“There’s a lot that goes on behind the scenes that people don’t see,” Boom explains. “People think it’s all roses. That everything is sweet. It’s not.”

Rather than lecture the audience, the film invites them into lived moments. Tension builds through character. Consequences unfold naturally. Humor punctuates the heaviness, not as distraction but as relief.

“We did not set out to make a comedy,” Gillen says. “But sometimes things were funny without us trying. And audiences responded to that.”

The result is a film that feels human. One that allows laughter to coexist with unease. One that understands that truth, when delivered gently, often lands harder.

Cast members recognized themselves in the story. Porsha, who portrays Carmen, describes the film as a warning disguised as entertainment.

“You gotta be careful who you work with,” she says. “It don’t matter what industry you’re in. You have to pay attention. You never know who you’re aligning yourself with.”

The film asks viewers to look closer. At contracts. At promises. At the cost of ignoring instinct.

Unlike films that use the Midwest as a generic stand in, Blood On The Turntables insists on Minnesota as itself. Neighborhoods are named. Streets are familiar. The setting is not ornamental. It is essential.

“I need Minnesota to take pride in being Minnesota again,” Boom says. “There’s a whole Black community here deeply rooted in hip hop, and that story hasn’t been told in forty years.”

For decades, Minnesota’s cultural narrative has often been flattened or misunderstood nationally. When Black stories appear, they are frequently framed as anomalies rather than continuities.

“There are people who don’t even believe Black people live here,” Boom says. “But we are here. And our stories matter.”

Robbin Piinkii Loyde feels that reclamation deeply.

“This is our city. Our movement. Our movie,” she says.

The film presents Minnesota not as a backdrop but as a participant. A place of creativity and conflict. Of ambition and restraint. Of voices long present but rarely amplified.

The absence of money forced clarity. There was no room for ego. No hierarchy to hide behind.

“We’re family,” Gillen explains. “Nobody was trying to eat more than the other. We lift each other.”

Scheduling was a constant challenge. Locations fell through. Everyone involved carried full lives outside the production. Fashion shows. Radio appearances. Other film projects. Parenting.

Yet the work continued.

“You can’t outshine someone when you’re building the same thing,” Piinkii says. “We all had our own shine.”

That philosophy translated directly onto the screen. Performances were shaped collaboratively. Scenes were adjusted through dialogue rather than demand. The environment was rigorous but affirming.

“There was no time for negativity,” Piinkii says. “We had one vision.”

Ask the cast when the film transformed from idea into inevitability and several will point to the same moment. A long table scene charged with tension and symbolism.

“When I finally saw it come together, I knew,” Porsha recalls. “I was like, this is cold.”

Behind the camera, Gillen remembers the trust required before proof existed.

“He had his vision. I had mine. And somehow it became one vision.”

Earlier still, before most of the film had been shot, came the moment that sealed its fate. A trailer filmed in a liquor store. Quick. Unpolished. Unavoidable.

“We shot a trailer when the movie barely existed,” Boom says. “Once we did that, there was no turning back.”

By announcing the film publicly, the team committed themselves to its completion. The promise now belonged not only to them but to the community watching.

Today, Blood On The Turntables streams on Boomz TV and digital platforms. Its reach extends beyond screens into conversations among aspiring filmmakers who see in it something rarely offered. Permission.

“I want to start a wave of movie makers here,” Boom says. “We already have the talent.”

For creators from underserved backgrounds, the film offers more than inspiration. It offers evidence.

Evidence that a movie can be made without waiting to be chosen.

Evidence that community can replace capital.

Evidence that grief can be transformed into creation.

Evidence that Minnesota stories deserve to be told by Minnesotans.

By the time Blood On The Turntables reached audiences, it had become something rare. Not because it was perfect, but because it existed at all.

Proof that access, not talent, is often the real barrier.

And proof that access, when institutions fail to provide it, can still be built by hand.