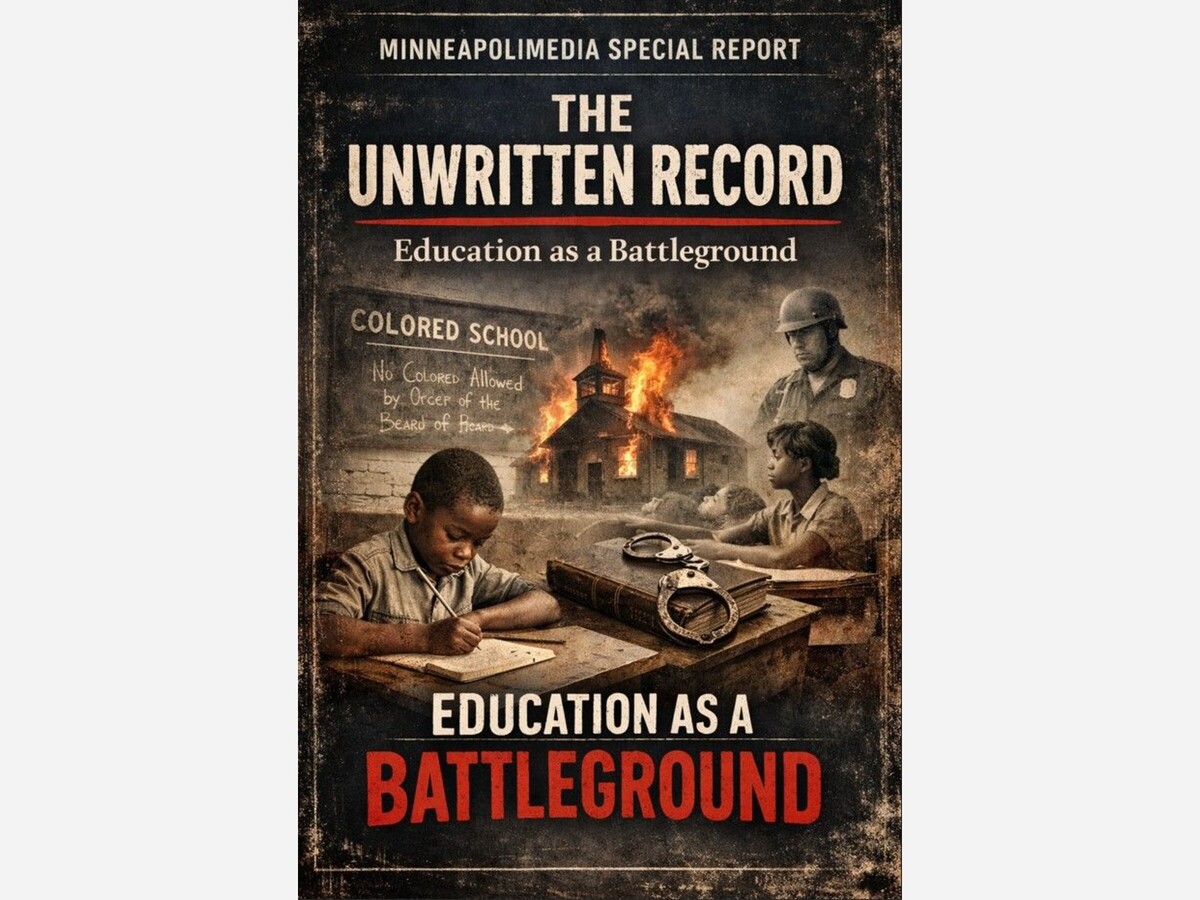

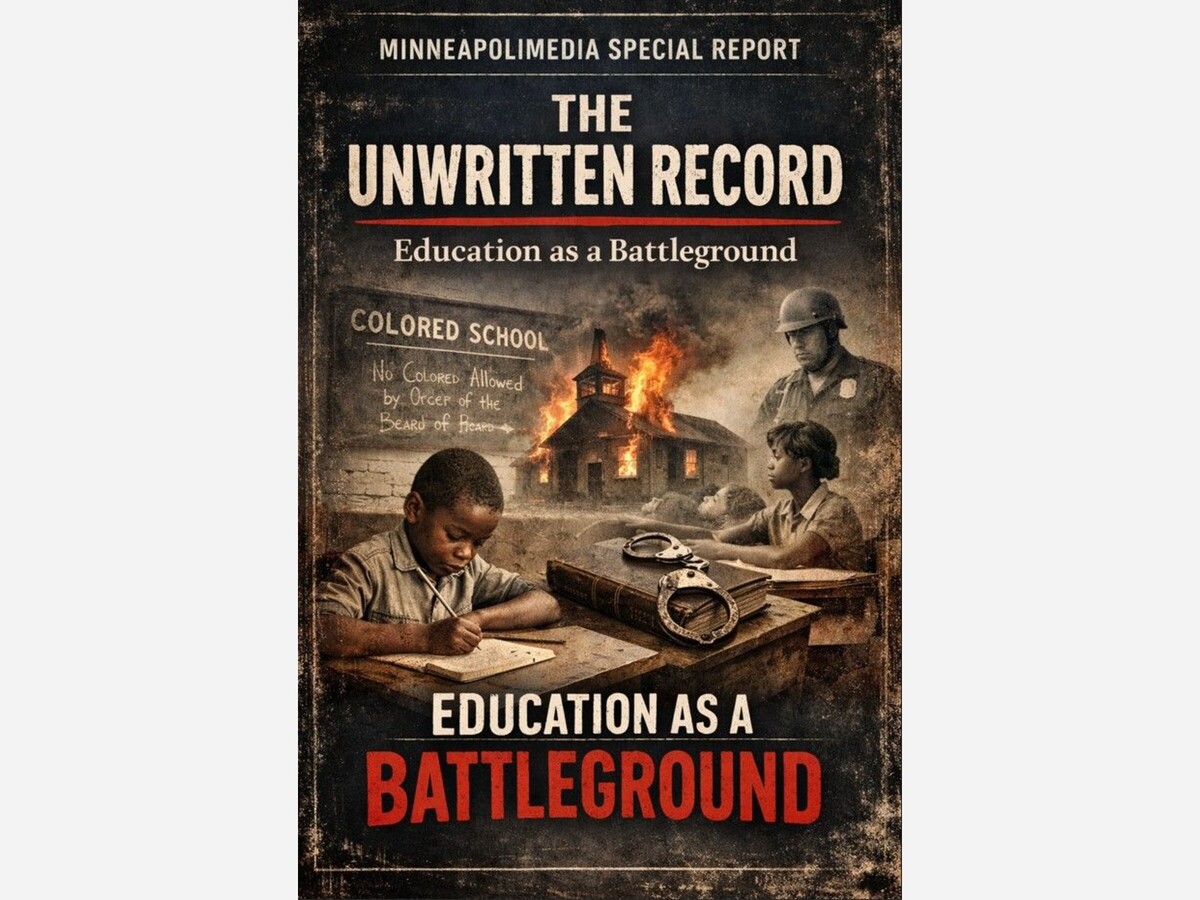

Image

Education has never been neutral in the American story.

From the earliest days of enslavement through the present, access to knowledge has functioned as a line of control. Who could read. Who could write. Who could teach. Who could define truth. These were not academic questions. They were political ones.

For African Americans, education was never simply a path to opportunity. It was a site of conflict. Knowledge threatened systems built on extraction and hierarchy. Illiteracy preserved dependence. Instruction created possibility.

The struggle over education was therefore a struggle over power.

Under enslavement, literacy among African Americans was treated as a danger to the social order. Laws across slaveholding states prohibited teaching enslaved people to read or write. Punishment was swift and severe, enforced not only through statute but through terror.

The logic was clear. Literacy enabled communication beyond surveillance. It allowed contracts to be read, passes to be forged, abolitionist ideas to circulate, and rebellion to be planned. Knowledge disrupted control.

Education was criminalized because it worked.

Yet instruction persisted. Enslaved people learned in secret, passing letters, practicing reading at night, teaching one another despite risk. The desire to learn became an act of resistance, sustained across generations.

When legal enslavement ended, the pursuit of education accelerated with extraordinary urgency.

African Americans of all ages sought schooling. Children and elders crowded into makeshift classrooms. Parents sacrificed wages to pay teachers. Communities built schoolhouses with their own labor when none were provided.

This demand was not naive. Formerly enslaved people understood that freedom without knowledge would be easily undermined. Education was treated as essential infrastructure for citizenship.

The response from white society was mixed. Missionaries and reformers assisted in some areas. In others, schools were burned, teachers attacked, and students threatened. The battlefield shifted, but it remained a battlefield.

As Reconstruction collapsed, segregation hardened.

Separate schooling became law and practice, justified by claims of equality that were never realized. African American schools received fewer resources, outdated materials, and inferior facilities. Teachers were underpaid. Class sizes were larger. Curricula were constrained.

This was not accidental underinvestment. It was policy.

Education became a mechanism to reproduce hierarchy. African American students were prepared for labor, not leadership. Instruction emphasized obedience rather than inquiry. Aspirations were narrowed deliberately.

Yet even under these conditions, educators and communities refused to surrender the purpose of schooling. Teachers taught beyond textbooks. Parents reinforced lessons at home. Schools became sites of affirmation as well as instruction.

Minnesota often presents itself as a place where educational inequity was less severe. This perception rests on omission rather than evidence.

African American students in Minnesota faced segregation through housing patterns, school zoning, and informal exclusion. Schools in African American neighborhoods were under-resourced. Access to advanced coursework and leadership opportunities was limited.

More subtly, curriculum functioned as a form of erasure.

Minnesota’s educational narratives often framed racial history as external. Enslavement was taught as southern. Civil rights as national. Local African American presence and struggle were minimized or ignored.

This approach allowed inequality to be treated as imported rather than produced. Students learned about injustice without learning responsibility.

Beyond access, education shaped understanding itself.

Textbooks framed African Americans primarily through enslavement and deficiency. Contributions were minimized. Resistance was softened. Achievement was exceptionalized rather than contextualized.

This framing had consequences. It taught African American students to see themselves as marginal to the state’s story. It taught white students to see inequality as accidental or resolved.

Education here did not merely reflect power. It reinforced it.

African Americans responded by reclaiming education on their own terms.

Historically African American schools, colleges, and universities emerged as spaces where intellectual development could occur without constant diminishment. Community programs supplemented public instruction. Cultural education filled gaps left by formal curricula.

Teachers acted as guardians of truth, often working against official guidelines to ensure students understood their history and potential.

Education became not only a path to opportunity, but a means of psychological survival.

The battleground has not disappeared. It has evolved.

Debates over curriculum, history, and inclusion continue to reveal discomfort with honest instruction. Efforts to restrict discussion of race, inequality, and systemic harm echo earlier attempts to control knowledge.

The language has changed. The logic remains.

A population that understands its history is harder to govern through myth.

Education shapes what a society believes about itself. It determines which problems are visible and which remain unnamed.

When African American history is minimized, inequality appears natural. When struggle is obscured, resistance appears irrational. When contribution is erased, demands for equity appear unearned.

Teaching honestly does not divide. It clarifies.

Education has always been contested because it determines the future.

African Americans understood this from the beginning. They pursued knowledge under threat, built schools under exclusion, and taught truth in the face of distortion.

The battleground was never about books alone. It was about citizenship.

A democracy that fears education reveals its own fragility.

To teach accurately is not to reopen conflict. It is to acknowledge that the conflict never ended.

This series exists because education is still a battleground, and memory remains contested ground.

The work of teaching honestly is not complete.