Image

By the time Officer Carlson walks a neighborhood, the work has often already begun.

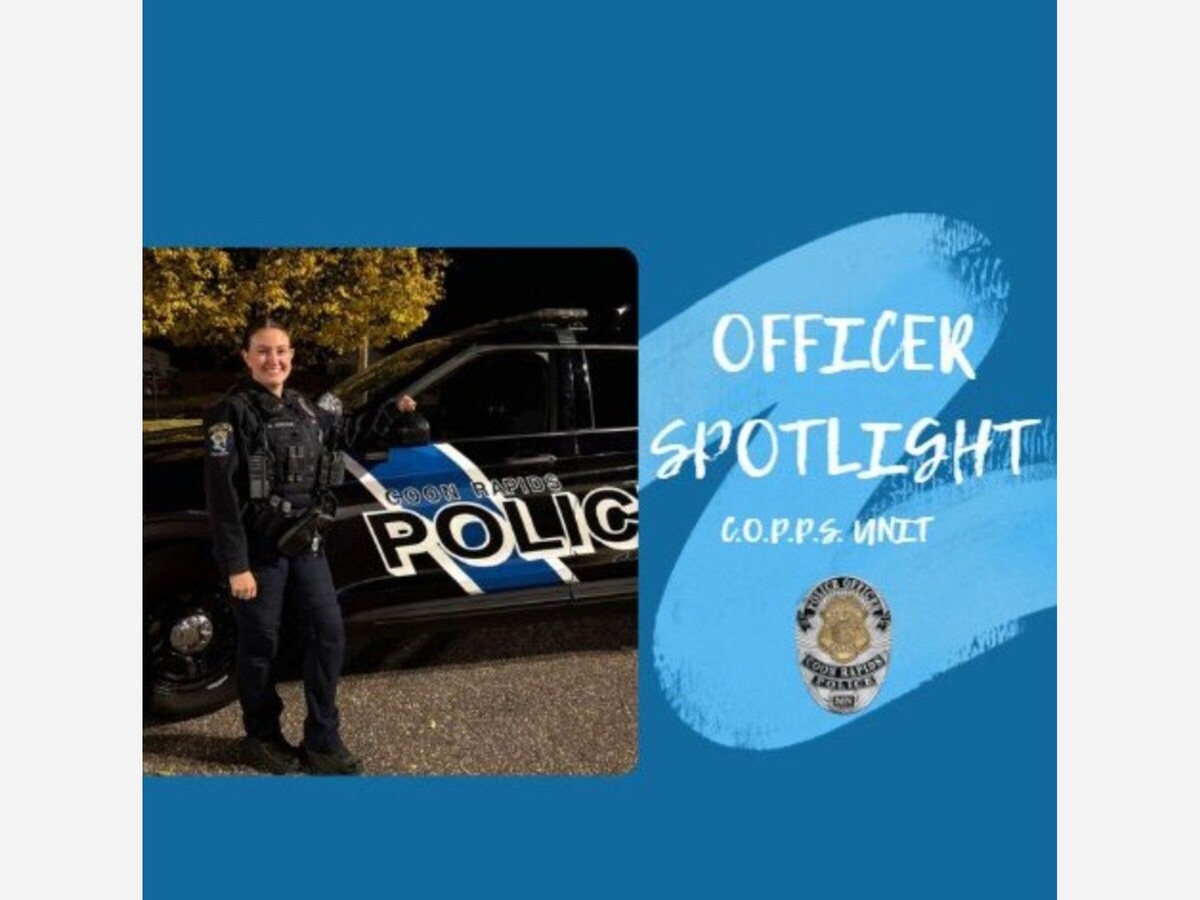

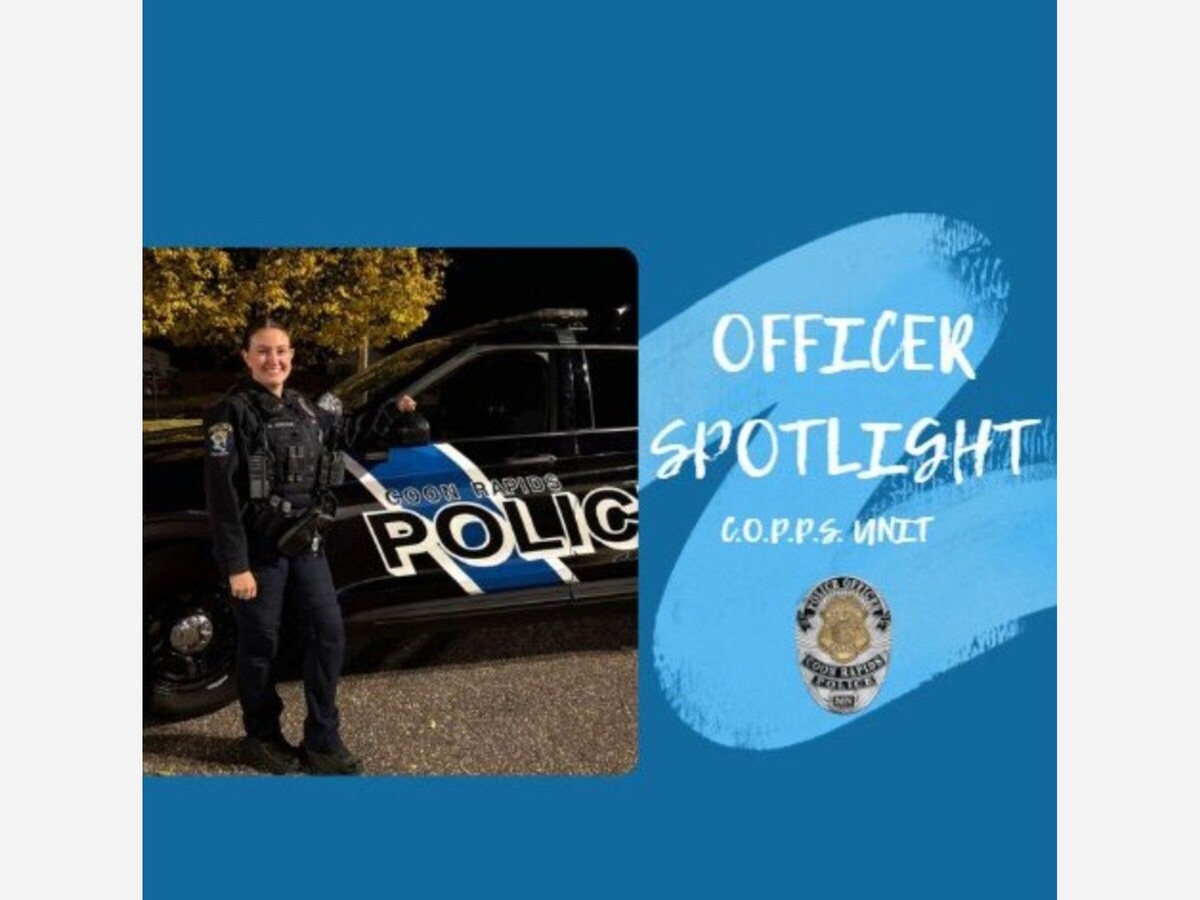

Community policing, at its most effective, rarely announces itself with flashing lights or blaring sirens. It unfolds in conversations with apartment managers, quiet check-ins with shop owners, mentoring moments in school hallways, and the slow, patient work of preventing harm before it happens. That is the terrain now occupied by Officer Carlson, the newest addition to the C.O.P.P.S. Unit at the Coon Rapids Police Department.

Carlson joined the department in early 2023 after three years with the Lino Lakes Police Department, bringing with her a background rooted largely in night-shift patrol, where officers often encounter people at their most vulnerable. Over the course of her career, she has served as a DWI Enforcement Officer, a Field Training Officer, and now as a member of the department’s Community Oriented Policing and Problem Solving unit, a specialized arm of the department dedicated to prevention, trust-building, and long-term solutions.

Unlike traditional patrol assignments that revolve around reactive 911 calls, the C.O.P.P.S. Unit operates on a different timeline and philosophy. Its focus is proactive rather than episodic, built around identifying patterns instead of isolated incidents.

C.O.P.P.S. officers work to pinpoint recurring “hot spots” for crime and quality-of-life concerns, whether that involves repeat disorder calls at an apartment complex, theft patterns affecting local businesses, or neighborhood tensions that have yet to erupt into criminal activity. Officers serve as liaisons between the department and community stakeholders, including business owners, property managers, and neighborhood groups, translating concerns into targeted responses.

A core component of the unit’s work includes crime prevention strategies such as Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), an evidence-based approach that reduces crime by modifying the built environment—improving lighting, visibility, access control, and natural surveillance to deter criminal behavior before it starts.

For Carlson, the assignment aligns closely with both her temperament and her training.

“I’ve always been interested in understanding people and the ‘why’ behind their actions,” she said. “That curiosity carries over into this work. If you understand the conditions creating a problem, you can often fix it before it escalates.”

Carlson’s role in the department extends well beyond enforcement. She serves as an advisor for the department’s Police Explorer Program, part of Learning for Life, an affiliate of the Boy Scouts of America that introduces young people ages 14 to 21 to careers in public safety.

As an advisor, Carlson helps guide Explorers through hands-on training that includes traffic stops, felony response scenarios, first aid, crisis intervention, and preparation for regional and national law enforcement competitions. The program emphasizes discipline, teamwork, and ethical decision-making, offering participants early exposure to the realities and responsibilities of policing.

She is also a mentor in Cops and Cardinals, a locally rooted initiative tied to Coon Rapids High School. The program is deliberately simple and deliberately human: officers spend time at the school, attend sporting events, eat lunch with students, and become familiar, approachable presences rather than distant authority figures.

The goal, department leaders say, is to humanize the badge while giving students a trusted adult they can turn to for guidance.

Carlson’s professional path reflects both specialization and trust. As a Field Training Officer, she was responsible for overseeing new recruits during their earliest weeks on the job, evaluating not only technical skills but judgment, communication, and adherence to department standards. Her work as a DWI Enforcement Officer required advanced training in impaired driving detection and standardized field sobriety testing, areas that demand precision and consistency.

Yet Carlson speaks most often about the personal experiences that inform her work.

She describes growing up in a hardworking, loving family that faced its share of challenges—experiences that, she says, taught her resilience, empathy, and a firm sense of right and wrong. Those lessons now guide how she approaches accountability in uniform.

“I draw from my own challenges to connect with people,” she said. “But connection doesn’t mean ignoring responsibility. It means helping where possible and intervening when necessary.”

That balance is captured in the quote Carlson says she lives by: “Don’t be a victim of your circumstances—be a victor.” The sentiment echoes the department’s broader emphasis on resilience, responsibility, and prevention.

Away from work, Carlson gravitates toward activities that recharge her: exploring coffee shops and boutique stores, hiking, traveling, and amateur photography. A recent trip took her to Sedona, Arizona, and this winter she has taken up downhill skiing. Above all, she values time with family and friends—wherever that time happens to be spent.

She also shared a lighthearted personal detail that quickly became a favorite among colleagues: she still has a baby tooth.

Asked for one crime-prevention message she wishes every resident understood, Carlson did not hesitate.

“If you think you should call 911, do it,” she said. “People worry about bothering the police, but early calls let us address problems before they grow. Waiting often makes it harder for us to help.”

It is a simple message, but one that reflects the philosophy of community policing itself: early intervention, shared responsibility, and trust between residents and those sworn to protect them.

As Officer Carlson steps into her role within the C.O.P.P.S. Unit, department leaders say her experience, mentorship, and people-centered approach strengthen a model of policing that depends less on reaction and more on relationship.

In a city where public safety increasingly hinges on prevention rather than response, much of the work happens quietly—one conversation, one student, one neighborhood at a time.