Image

In the antebellum South, it was a crime to teach an enslaved person to read.

After Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, several Southern states strengthened anti-literacy laws. In Virginia, legislation prohibited teaching enslaved individuals to read or write. Violators faced fines and imprisonment.

The reasoning was explicit.

Literacy enabled communication.

Communication enabled organization.

Organization enabled resistance.

To deny literacy was to deny mobility of thought.

Education was recognized, even by those who opposed it, as power.

The battle over African American education did not begin with integration. It began with prohibition.

Under slavery, literacy was perceived as destabilizing. Enslaved people who learned to read gained access to abolitionist texts, forged passes, interpreted contracts, and read scripture independently.

Frederick Douglass described learning to read as the moment he understood both the injustice of his condition and the possibility of resistance.

Slaveholders understood the same.

Anti-literacy statutes functioned as preventative counterinsurgency.

The denial of education was not oversight. It was strategy.

If a population cannot read the law, it cannot challenge it.

If a population cannot access written language, it cannot control narrative.

Education was restricted to maintain hierarchy.

After the Civil War, newly freed African Americans prioritized education with urgency.

Freedmen’s Bureau records show rapid construction of schools across the South. Black communities raised funds, donated land, and built structures often before federal support arrived.

Northern missionary societies contributed teachers and materials, but the demand came from formerly enslaved communities themselves.

In 1870, literacy among African Americans was estimated at approximately 20 percent. By 1900, it had risen dramatically.

This increase did not occur because education was generously offered. It occurred because it was aggressively pursued.

Families sacrificed labor hours and scarce income to support schooling.

Education was not peripheral. It was foundation.

The 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson legalized segregation under the doctrine of separate but equal.

In practice, separate was rarely equal.

School funding disparities were stark. White schools received newer buildings, more supplies, longer terms, and better-paid teachers. Black schools operated with outdated materials and shorter academic calendars.

The imbalance was not hidden. It was normalized.

Local property tax funding models entrenched inequality. Communities denied property investment through redlining and wage suppression generated less tax revenue, reinforcing school disparities.

Education became geography.

Access to quality schooling followed access to capital.

In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education declared segregated public schools unconstitutional.

The language was clear: separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

Yet implementation met resistance.

Southern states adopted strategies of “massive resistance,” closing public schools rather than integrating them. Some districts created private academies to circumvent desegregation.

Even in northern states where segregation was not mandated by statute, de facto segregation persisted through housing patterns.

Brown changed law. It did not immediately change infrastructure.

The struggle moved from courtroom to district boundary.

Education is not only about buildings. It is about content.

For much of American history, textbooks minimized African American contributions outside of enslavement and civil rights.

Narratives often framed African Americans as peripheral actors rather than central builders.

Control over curriculum shapes national memory.

Debates over inclusion of African American history, slavery’s brutality, systemic racism, and contemporary inequities are not recent phenomena. They reflect long-standing anxiety over who defines the national story.

If education determines civic identity, then curriculum becomes political territory.

The question is not only who sits in the classroom.

It is what the classroom says.

Minnesota frequently ranks among the top states in overall educational performance.

Yet it also exhibits some of the largest racial achievement disparities in the nation.

Public discussion often frames this as an achievement gap.

The phrase gap describes measurement difference. It does not explain origin.

Housing segregation patterns, school funding formulas tied to property tax, disciplinary disparities, and differential access to advanced coursework contribute to outcome differences.

When achievement is discussed without architecture, accountability diffuses.

Education in Minnesota is not segregated by law. It is shaped by geography, zoning, and funding structures.

The battleground has shifted from explicit prohibition to structural design.

Educational inequality also manifests in disciplinary practices.

National data shows that African American students are disproportionately suspended and expelled compared to white peers for similar behaviors.

Suspension removes students from instructional time. Repeated exclusion increases risk of academic disengagement.

This dynamic intersects with broader criminalization patterns.

When discipline becomes exclusion rather than restoration, education loses protective function.

Schools are expected to prepare students for civic participation.

When they become sites of removal, the mission shifts.

Access to higher education has also been contested.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities emerged because African Americans were excluded from many predominantly white institutions.

Even after formal barriers fell, informal gatekeeping persisted through admissions practices, standardized testing emphasis, and financial barriers.

Student debt burdens disproportionately impact African American graduates due to lower intergenerational wealth.

The promise of higher education as a mobility pathway intersects with labor and wealth history.

Education is an opportunity only when structural barriers are acknowledged.

In the twenty-first century, education has expanded into digital space.

Access to broadband internet, devices, and quiet study environments became especially visible during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Communities with limited digital infrastructure faced disproportionate disruption.

The digital divide is an extension of housing and income inequality.

Education remains tied to material conditions.

Across centuries, the pattern holds.

Under slavery, literacy was criminalized.

After emancipation, education was self-built.

Under Jim Crow, funding was unequal.

After Brown, segregation persisted through geography.

In modern eras, funding formulas and discipline disparities maintain inequality.

Education has never been simply instructional.

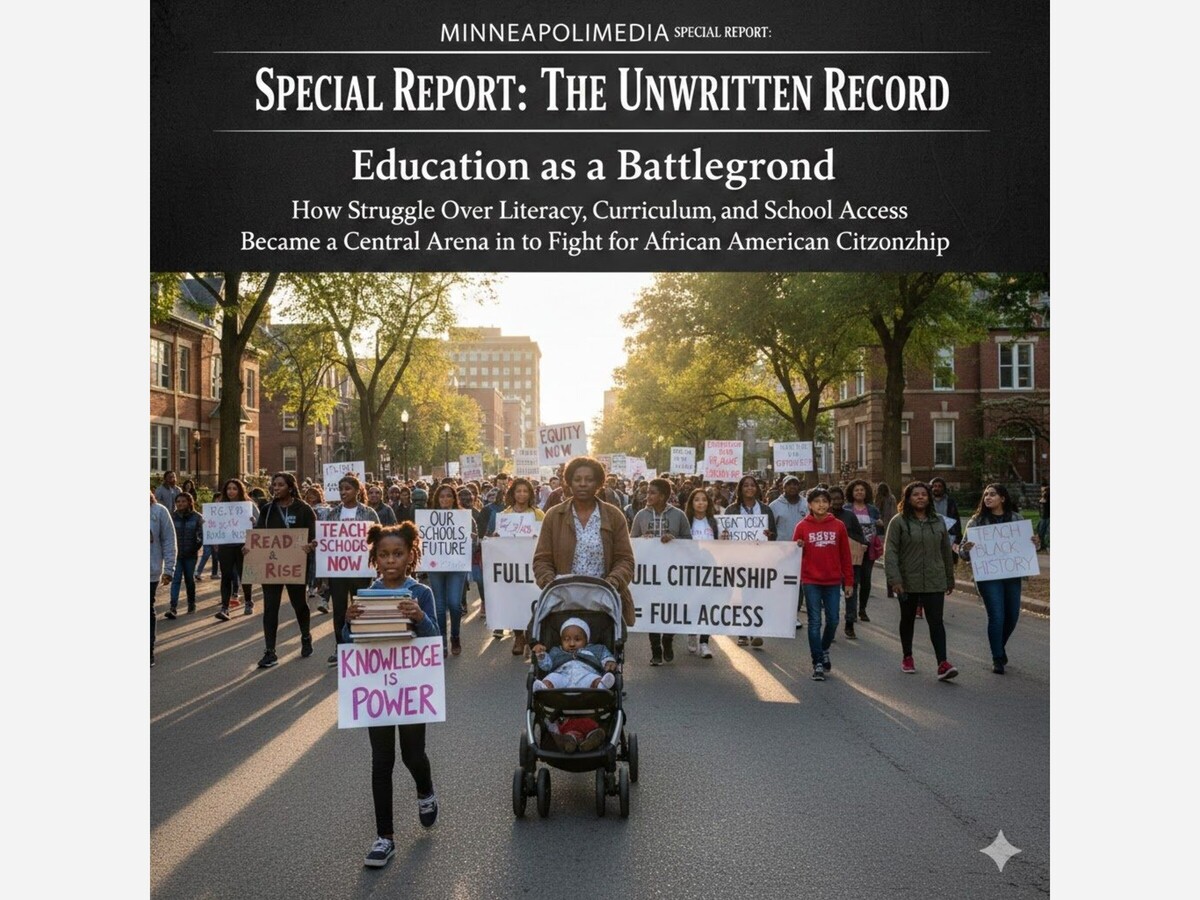

It has been a battlefield over citizenship.

To control education is to shape who can interpret law, who can compete in labor markets, who can narrate history.

The struggle for African American education has always been about more than school.

It has been about full civic participation.

African American communities have consistently treated education as essential to freedom.

They built schools when denied them.

They litigated for integration.

They demanded curriculum inclusion.

They organized for funding equity.

The record shows not passive reception but persistent pursuit.

Education was targeted because it mattered.

It remains contested because it still matters.

If democracy depends on informed participation, then access to accurate and equitable education is not optional.

It is foundational.

And the history of that struggle belongs in the record.