Image

On a winter morning decades ago, a child opened a history textbook in an American classroom and learned, without being told, that they had arrived late to the story.

The pages were full. Wars were fought. Laws were passed. Presidents were named. Progress marched forward. But nowhere, not in the margins or the footnotes, was there room for the people who looked like them, sounded like their grandparents, or carried the memory of a journey that did not begin at Plymouth Rock.

That silence was not accidental. It was authored.

Black History Month exists because that silence was never neutral. It exists because omission is a form of power. It exists because forgetting is not passive. It is practiced.

Every February, the United States pauses to acknowledge African American history. But this month was never meant to be a pause. It was meant to be a correction.

In 1915, historian Carter G. Woodson confronted an American truth that was both obvious and dangerous. The nation had built its identity while erasing the intellectual, political, cultural, and economic contributions of African Americans. History books rendered people of African descent as objects of history rather than its authors.

Woodson understood something foundational. A people denied their past are denied their future.

In response, he co founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. In 1926, the organization declared the second week of February Negro History Week. It was not conceived as a celebration. It was conceived as an act of refusal.

Refusal to accept invisibility.

Refusal to allow distortion to harden into fact.

Refusal to permit the next generation to inherit amnesia as education.

The week was placed deliberately between the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, figures whose lives intersected with the unfinished work of freedom and the abolition of enslavement. Schools, churches, and civic organizations began observing the week not because it was comfortable, but because it filled a void that could no longer be ignored.

For decades, one week carried the weight of centuries.

In 1976, amid the United States bicentennial, President Gerald Ford expanded that recognition, urging Americans to honor the accomplishments of African Americans across every field of human endeavor. Negro History Week became Black History Month, not as an expansion of celebration, but as an acknowledgment of scale.

The history had always been there. The country was simply being asked to look.

Black History Month does not honor a highlight reel. It honors a continuum.

It honors the enslaved Africans brought to this land in the early seventeenth century whose labor created wealth they were forbidden to claim. It honors those who survived reconstruction only to face lynching, segregation, redlining, and systematic exclusion. It honors educators who taught when teaching was illegal. Journalists who published when truth was dangerous. Artists who created beauty in a nation that questioned their humanity.

The names often recited each February matter.

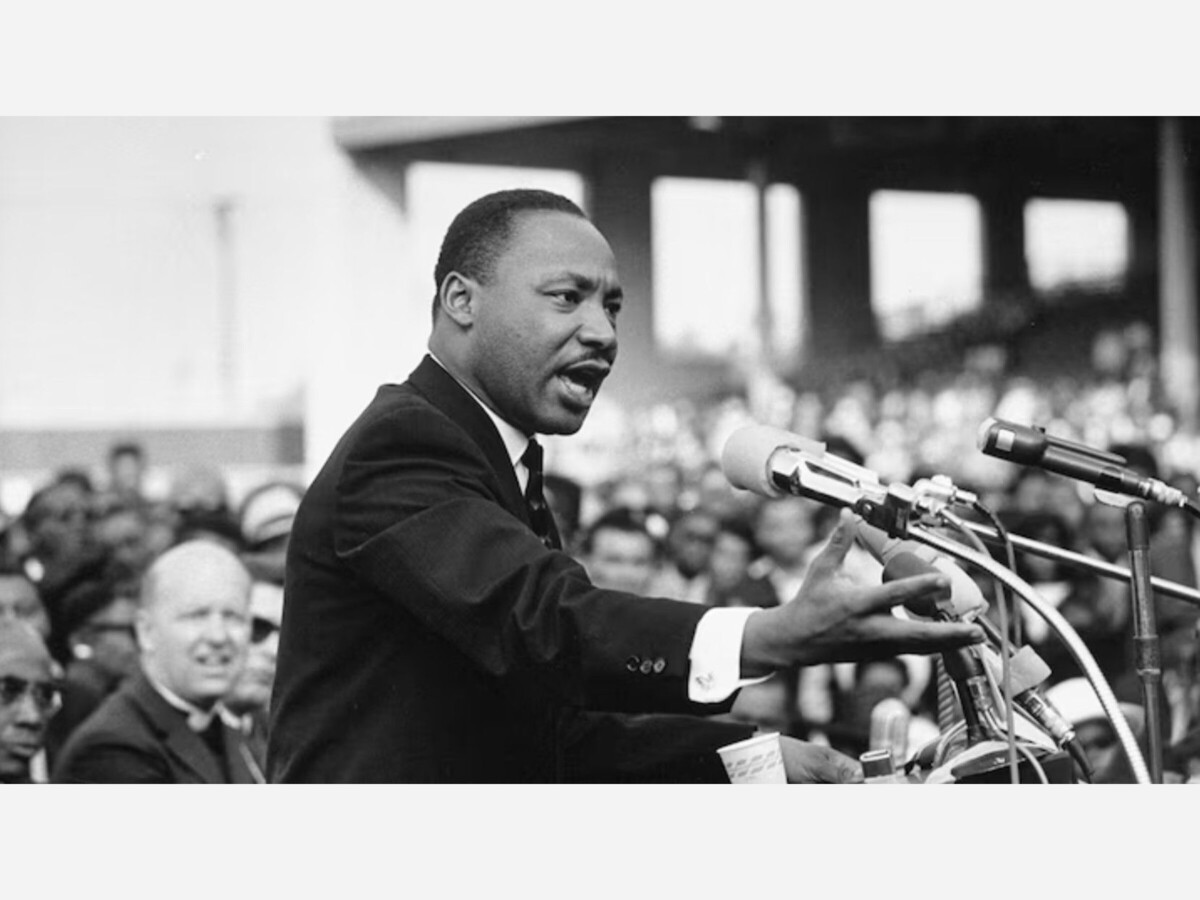

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave moral language to a movement that reshaped the nation’s conscience. Thurgood Marshall dismantled legalized segregation through the law itself. Mae Jemison expanded the boundaries of who belongs in science and exploration. Barack Obama’s election marked a political milestone once considered impossible.

But Black History Month is not about exceptional individuals rising above circumstances. It is about a people expanding the meaning of democracy in spite of them.

Nearly a century after its creation, some ask whether Black History Month is still necessary. The answer lies not in history, but in the present.

African American history remains unevenly taught. Contributions are celebrated while systems are softened. Courage is highlighted while resistance to that courage is minimized. The same erasures Carter G. Woodson confronted have not disappeared. They have adapted.

Memory remains contested ground.

That is why this observance continues not only in the United States, but in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands. Museums curate exhibits. Schools host assemblies. Films are screened. Lectures are delivered.

These efforts matter. But they are not the point.

The point is not a month of attention followed by eleven months of silence. The point is integration. Continuity. Truth telling that does not require a calendar reminder.

The visual language that often accompanies Black History Month tells this story without words. Faces look backward and forward at once. Hands are raised not in surrender, but in declaration. Shapes repeat, echo, and transform. History is not frozen. It is alive.

Black History Month is not about closing a chapter. It is about refusing erasure.

It asks the nation to confront who it has been honest with, and who it has not. It asks educators to teach fully, journalists to report responsibly, institutions to reckon sincerely, and communities to listen deeply.

Carter G. Woodson did not create a week, and later a month, so African American history could be temporarily acknowledged. He created it so that one day, it would no longer need to be set aside at all.

Until that day arrives, February remains an act of responsibility.

Not as a gesture.

Not as a performance.

But as a promise to remember forward.