Image

February is Black History Month. This series documents the unwritten record. We invite our community to help complete it.

History is not only what is written. It is also what is intentionally omitted.

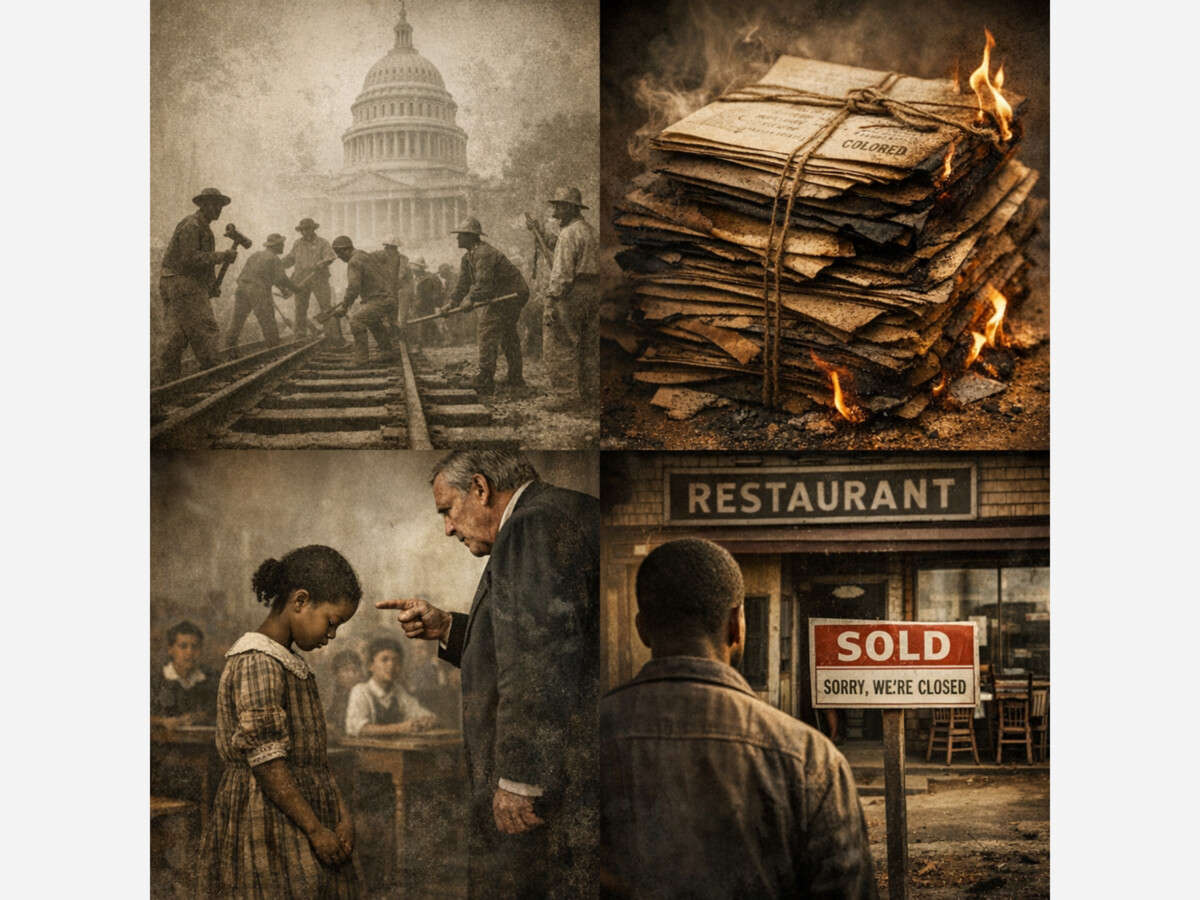

The story of African Americans in the United States has never suffered from a lack of substance. It has suffered from a lack of permission. From the earliest days of the republic, the nation made a deliberate choice not merely to subordinate people of African descent, but to strip their labor, intellect, resistance, and humanity from the official record. What followed was not forgetfulness. It was designed.

Erasure did not happen by accident. It was constructed.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, African Americans were present in every sector of American life. They cleared land, built roads, erected courthouses, staffed ports, forged iron, cooked meals, raised children, and cultivated crops that financed the nation’s early wealth. Yet the documents that became textbooks, municipal histories, and institutional archives routinely framed these developments as if they emerged from nowhere.

Cities appeared fully formed. Economies seemed self-generating. Democracy was presented as an inheritance untainted by exploitation.

This omission was not neutral. It functioned as a moral shield.

By removing African Americans from the narrative of nation-building, the United States avoided confronting the contradiction at its core. A nation that defined itself by liberty depended on coerced labor. A democracy that celebrated representation denied it to millions. Erasure allowed these contradictions to coexist without consequence.

The architecture of erasure operated through multiple channels. Early historians prioritized political leaders and landowners while dismissing laborers as interchangeable and unworthy of record. Census data counted bodies but not stories. Property law reduced people to assets, then removed them from history once emancipation disrupted that framework.

When African Americans created their own newspapers, schools, and institutions, those records were often underfunded, destroyed, or excluded from mainstream archives.

Education systems formalized this absence. For much of the twentieth century, American students encountered African Americans primarily in the context of enslavement, then disappeared until a brief reappearance during the civil rights era. Generations were taught that African Americans entered history as victims and exited once legal equality was declared.

This structure denied continuity. It erased agency. It suggested completion where none existed.

The consequences of this narrative architecture persist.

Public policy does not operate in a vacuum. Decisions about housing, healthcare, education funding, and criminal justice are shaped by assumptions about who has contributed, who has benefited, and who is perceived as a burden. When African Americans are absent from the story of national creation, inequality appears accidental rather than engineered. Disparities are framed as personal failure instead of historical outcome.

Erasure also distorts empathy.

It is easier to dismiss a community whose sacrifices are invisible. It is easier to question belonging when contribution is unacknowledged. The removal of African American achievement from public memory has made it possible for injustice to repeat itself under the guise of neutrality.

This pattern extended beyond the South. Northern states, including those that opposed slavery, cultivated their own myths of innocence.

African Americans in places like Minnesota were present long before statehood, working as laborers, entrepreneurs, soldiers, and organizers. Yet local histories often rendered them invisible, reinforcing the illusion that racial inequality was imported rather than embedded.

The archival silence was not total.

African Americans resisted erasure by creating parallel records. Churches kept minutes. Families preserved oral histories. Mutual aid societies documented membership. Newspapers chronicled achievements ignored elsewhere. These sources reveal a vibrant civic life operating beneath the official narrative, not as a supplement, but as an alternative foundation.

Yet parallel records were forced to compete with state-sanctioned history. When funding, preservation, and legitimacy are unevenly distributed, memory becomes hierarchical. What survives is mistaken for what mattered most.

The struggle over history is therefore a struggle over power.

To be remembered accurately is to make claims on the present. It is to assert that policy must account for precedent, that justice requires context, and that repair cannot occur without acknowledgment.

Correcting erasure is not about rewriting history. It is about completing it.

This completion demands more than commemorative months or symbolic gestures. It requires structural change in how history is taught, funded, archived, and applied. It requires institutions to interrogate their own records and silences. It requires the media to treat African American history not as a niche subject, but as central to understanding the nation itself.

Most importantly, it requires honesty.

A society that refuses to tell the full story cannot govern itself justly. Erasure does not merely distort the past. It governs the present by limiting what solutions seem possible and what accountability feels necessary.

To confront the architecture of erasure is to accept that history has been managed, not merely inherited. It is to recognize that memory itself is a civic responsibility.

The question before us is not whether African American history belongs at the center of the American story. The evidence has always been clear.

The question is whether the nation is prepared to live with the truth it reveals.

To understand the architecture of erasure, one must look at the soil beneath our own feet. The following case study examines how these national patterns of silence manifested in the history of Anoka County.

The architecture of erasure is not a concept confined to national archives. Its blueprints are visible in the very soil of Anoka County.

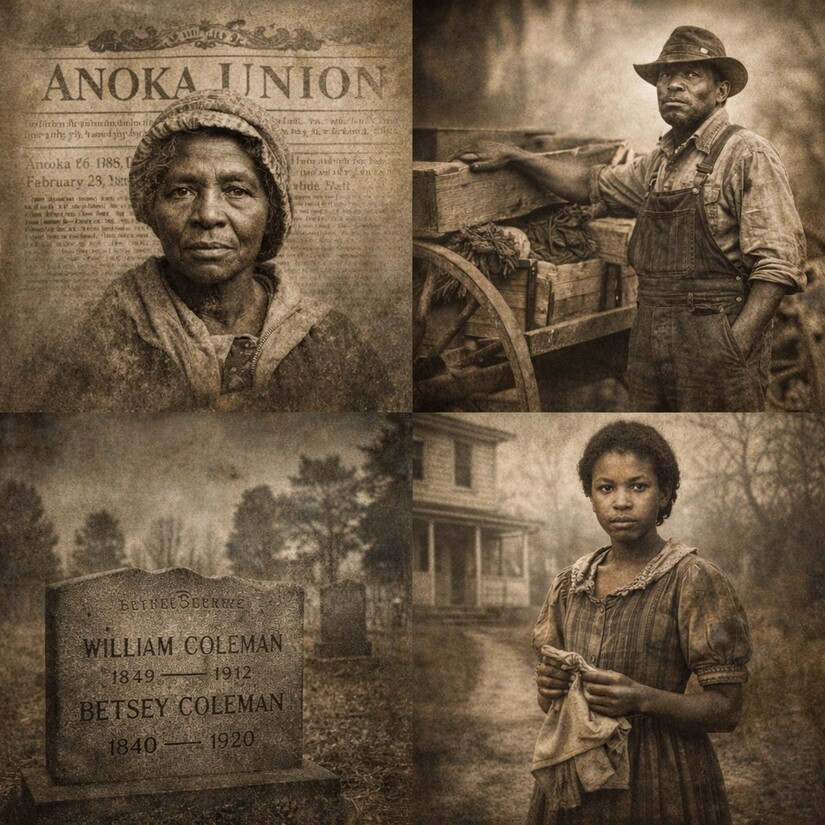

While mainstream local histories often begin with the 1844 arrival of European settlers, there exists a parallel, older story that persists despite more than a century of archival silence.

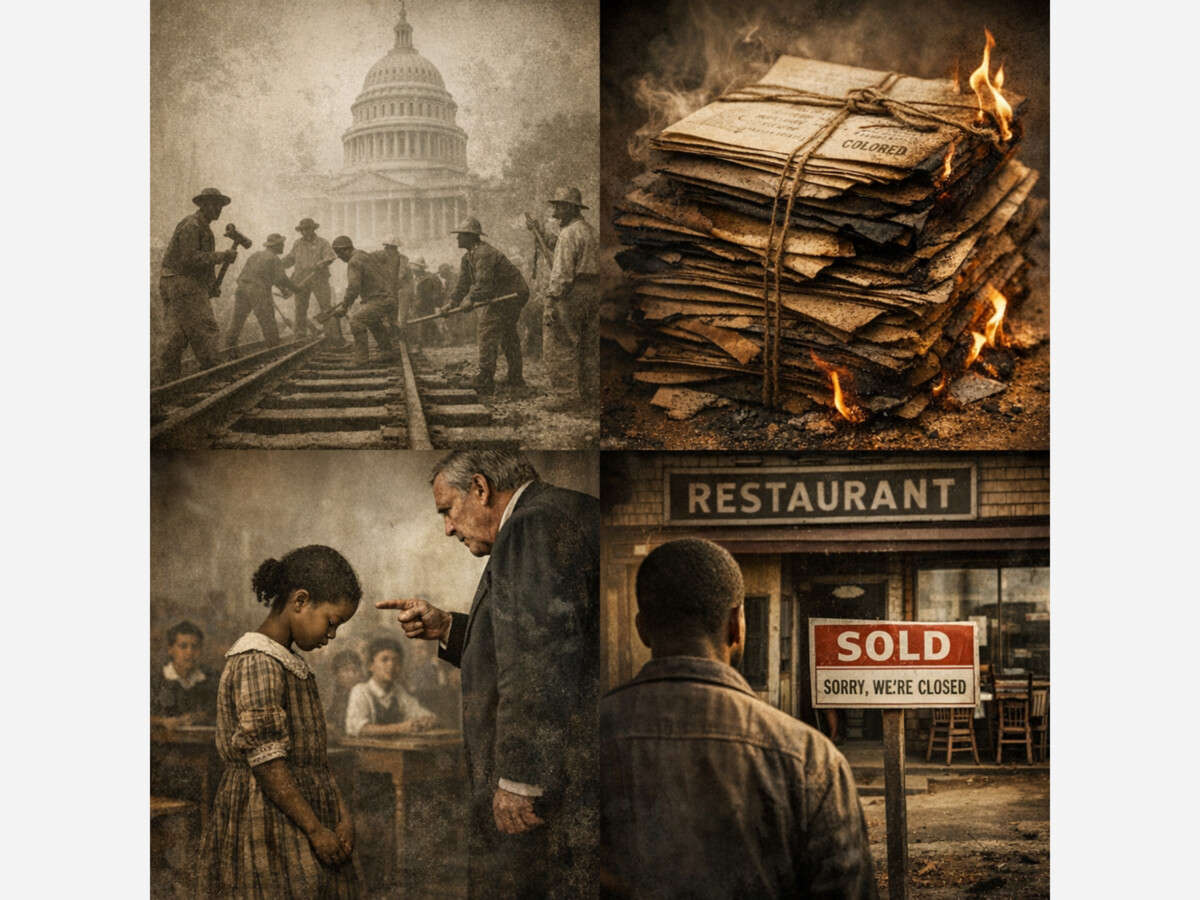

In February 1886, a fourteen-year-old girl named Susanna Coleman was summoned to the principal’s office at Anoka High School. Her infraction was trivial. She was accused of chewing a piece of paper.

The punishment was not.

The principal, a Harvard graduate named Jotham Henry Cummings, whipped her hands with a horsewhip until they bled.

In an era when the legal and social structures of Minnesota were designed to render Black women invisible, Susanna’s mother, Betsey Coleman, did the unthinkable. She did not retreat. She wrote an eloquent, searing letter to the Anoka Union, publicly accusing the principal of excessive force.

Betsey Coleman had been sold into slavery in Missouri at four years old. She knew the weight of a whip. By the time she reached Anoka, she had transformed herself from property into a citizen who demanded an accounting.

Her letter was an act of architectural sabotage. She forced the local record to acknowledge a violence it preferred to ignore.

The Colemans were not visitors to the North Metro. They were its builders.

William Coleman worked as a teamster, moving the goods that fueled Anoka’s early economy. Betsey worked as a washwoman, sustaining households whose names now appear on street signs and civic landmarks. By 1900, Susanna had become a dressmaker, her needle and thread part of the literal fabric of the community.

Today, William and Betsey Coleman are buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Anoka. Their headstones are silent. Their presence remains an unresolved challenge to the myth that racial complexity arrived late in the North Metro.

Erasure continued into the twentieth century through the gatekeepers of land and capital.

In Ramsey, the experience of the Dan Laws family exposes the mechanics of exclusion disguised as neutrality. When Laws attempted to open a restaurant, he was met with refusals, evasions, and walls of sudden “sold” signs.

When he finally located property at the corner of County Roads 5 and 47, he asked the broker plainly whether his race would be an issue. The broker’s response was blunt.

“Is your money green?”

It was a rare moment of honesty in a system that usually concealed discrimination behind procedure.

To document the North Metro truthfully is to search for families like the Colemans in the margins of census rolls and forgotten letters. It is to understand that Coon Rapids, Blaine, Fridley, and Anoka did not emerge fully formed from farmland and neutrality.

They were shaped by who was permitted to own land and who was forced to labor in silence.

Correcting the record is not a gift we give to the past. It is a debt we pay to the truth.

At MinneapoliMedia, we recognize that every street in Anoka County carries two histories. The one that was written, and the one we are finally prepared to hear.

This edition marks the beginning of MinneapoliMedia’s commitment to documenting the Parallel Records of our community. History is a civic responsibility.

If you have family records, photographs, or stories that have been excluded from the official narrative of the North Metro, we invite you to contact our archives at: minneapolimedia@gmail.com .

These records help complete a history that was never neutral and never finished.