Image

Freedom did not arrive in the United States with instructions.

When enslavement formally ended, millions of African Americans stood at the edge of a nation that had extracted their labor, denied their humanity, and now offered legal emancipation without land, protection, or material support. The prevailing assumption, repeated for generations, was that formerly enslaved people were unprepared for citizenship, incapable of self-governance, and dependent by nature.

History records the opposite.

What followed emancipation was not passivity or confusion. It was one of the most ambitious institution-building efforts in American history. Formerly enslaved people constructed churches, schools, mutual aid societies, newspapers, fraternal orders, and civic associations at a pace and scale that rivaled state formation itself. These were not symbolic gestures. They were deliberate responses to abandonment, exclusion, and violence.

American democracy did not simply survive emancipation. It was rebuilt by those who had been denied access to it.

Emancipation delivered freedom without infrastructure. There was no land redistribution. No guaranteed wages. No public welfare system. No protection from retaliation. Southern states quickly erected Black Codes that restricted movement, labor, and political participation. Vigilante violence enforced racial hierarchy where law hesitated.

In this vacuum, African Americans confronted a fundamental reality. If citizenship was to exist in practice, it would have to be constructed from the ground up.

The institutions that emerged were not aspirational. They were essential.

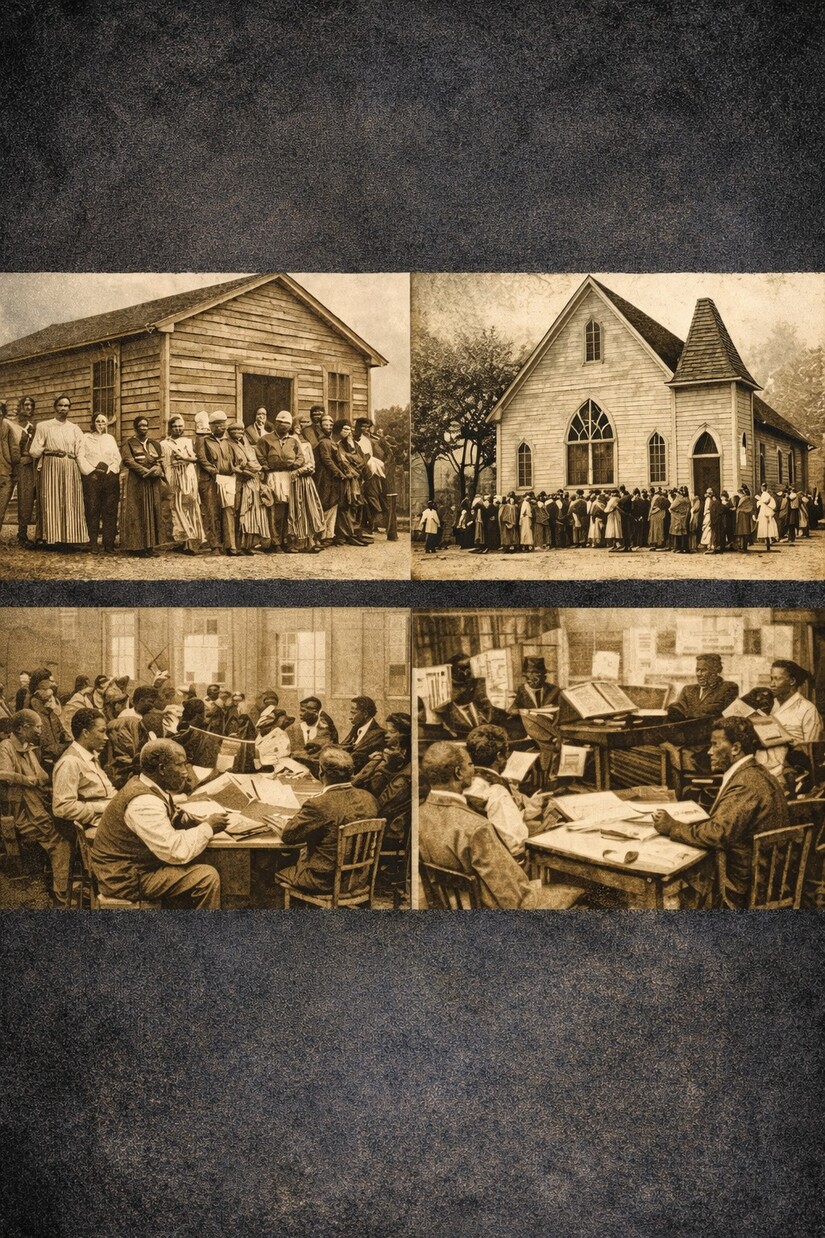

African American churches were among the first stable institutions created by formerly enslaved people, and they quickly became the most powerful. These were not merely houses of worship. They functioned as governments in miniature.

Churches collected dues, managed budgets, recorded minutes, elected officers, resolved disputes, and enforced accountability. They hosted schools, housed political meetings, and coordinated mutual aid. Ministers often served as community representatives, negotiators, and strategists.

Within church governance, African Americans practiced democracy long before the state reliably allowed them to vote. Parliamentary procedure, elections, and collective decision-making were not abstract ideals. They were daily disciplines.

The church offered something the nation withheld: structure.

Education was treated as a threat under enslavement. Literacy empowered resistance, contract negotiation, and memory. After emancipation, the urgency to learn was immediate and relentless.

Formerly enslaved people built schools with their own labor and limited resources. They raised money through church collections and tuition paid in coins, crops, or labor. They hired teachers, demanded curriculum, and insisted on permanence.

These schools were not welcomed. They were burned, vandalized, and targeted by intimidation. Teachers were threatened. Students were attacked. Still, instruction continued.

Education was understood not simply as self-improvement, but as civic defense. To read was to contest exploitation. To write was to enter the public record. To teach history was to dismantle the lie of inferiority.

A democracy without education is a performance. African Americans refused to perform.

Excluded from banks, insurance, and public welfare, formerly enslaved people created mutual aid societies that functioned as early systems of economic governance.

These organizations provided sickness benefits, burial funds, emergency relief, and small loans. They supported widows, cared for children, and stabilized families during economic shocks. Rules were written. Officers were elected. Ledgers were kept.

Mutual aid was not charity. It was a collective response to structural exclusion.

These societies taught financial discipline, shared responsibility, and long-term planning in an economy designed to extract labor without offering security. They were proof that economic instability was imposed, not inherent.

In a nation where mainstream newspapers routinely ignored or distorted African American life, formerly enslaved people and their descendants built their own press.

These newspapers documented births, deaths, marriages, achievements, and injustices. They published editorials articulating political philosophy. They reported on racial violence when others remained silent. They encouraged voting, challenged discriminatory laws, and connected local struggles to national movements.

The Black press did more than report democracy. It preserved it.

By placing African American voices into print, these papers asserted permanence and authority. They rejected the role of subject and claimed the role of citizen.

What is often described as cultural development was, in fact, organized resistance. Each institution represented a refusal to accept dependency as destiny.

These structures produced leadership. Ministers became legislators. Teachers became organizers. Editors became advocates. Skills learned in parallel institutions later fueled formal political participation when access widened.

American democracy did not absorb African Americans and then benefit from their contributions. African Americans developed democratic capacity while excluded from the state, then carried that capacity into public life when entry became possible.

The story of institution building unsettles a convenient narrative. It challenges the belief that freedom was granted rather than demanded, and that progress flows from benevolence rather than organization.

Acknowledging this record requires admitting that African Americans were often more committed to democratic practice than the governments that governed them.

To minimize this history is to preserve the fiction that inequality resulted from incapacity rather than exclusion.

The institutions built by formerly enslaved people did not disappear. Many remain active today, though often disconnected from their origins. Churches still anchor neighborhoods. Community organizations still provide services. African American newspapers continue to shape civic discourse.

These are not relics of survival. They are living infrastructure.

When modern debates question African American civic engagement, institutional trust, or readiness for governance, they do so in defiance of a record that proves otherwise.

From enslavement to institution building is not a story of transition. It is a story of authorship.

Formerly enslaved people did not wait for democracy to include them. They practiced it into existence. They built systems capable of sustaining communities long enough to demand rights, protections, and recognition.

This history does not belong in the margins. It belongs at the center of the American story.

Not as inspiration.

Not as exception.

But as foundation.