Image

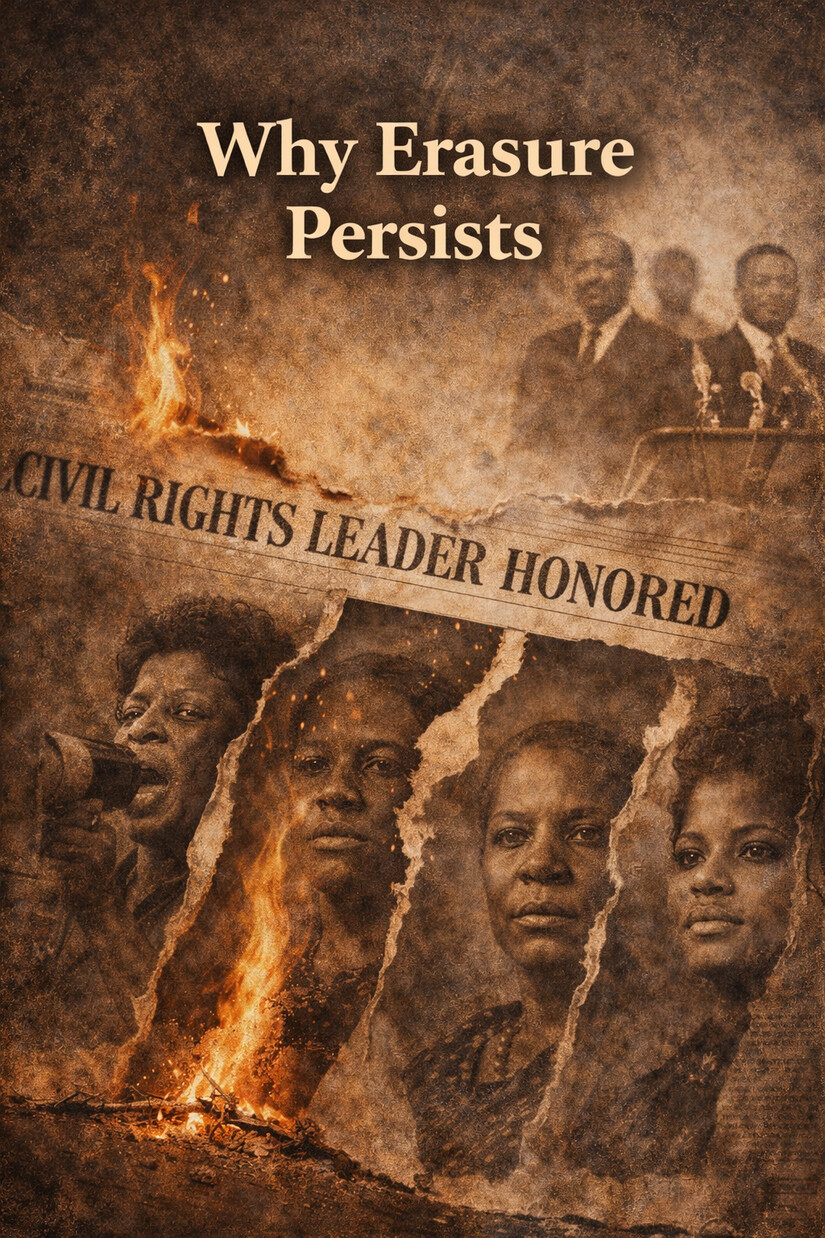

Movements are often remembered through microphones.

History tends to compress collective struggle into a few visible figures, usually men standing at podiums, delivering speeches that become quotations in textbooks. This narrowing is convenient. It produces heroes. It simplifies narrative. It makes movements appear charismatic rather than constructed.

But movements do not run on charisma. They run on infrastructure.

And in the long arc of African American history, that infrastructure was built, sustained, and strategically directed by women whose names were often minimized, sidelined, or omitted altogether.

To center African American women is not to rebalance the spotlight. It is to restore structural truth.

Every institution examined in this series, from church to school to protest to economic survival, depended on the labor and strategy of women. Without them, the architecture collapses.

Under enslavement, African American women carried a burden that was both economic and reproductive. They labored in fields and domestic spaces. They endured sexual exploitation that was codified in law and normalized in practice. They raised children who could be sold away. They preserved kinship under constant threat of separation.

Yet even within this violent structure, African American women functioned as strategists of survival.

They preserved oral histories when written record was denied. They transmitted cultural memory. They taught children language, belief, and resistance. They created informal networks of care that allowed families to endure.

Survival under enslavement required organization. It required calculation. It required leadership that operated quietly because visibility invited punishment.

The survival of community was not accidental. It was engineered daily by women.

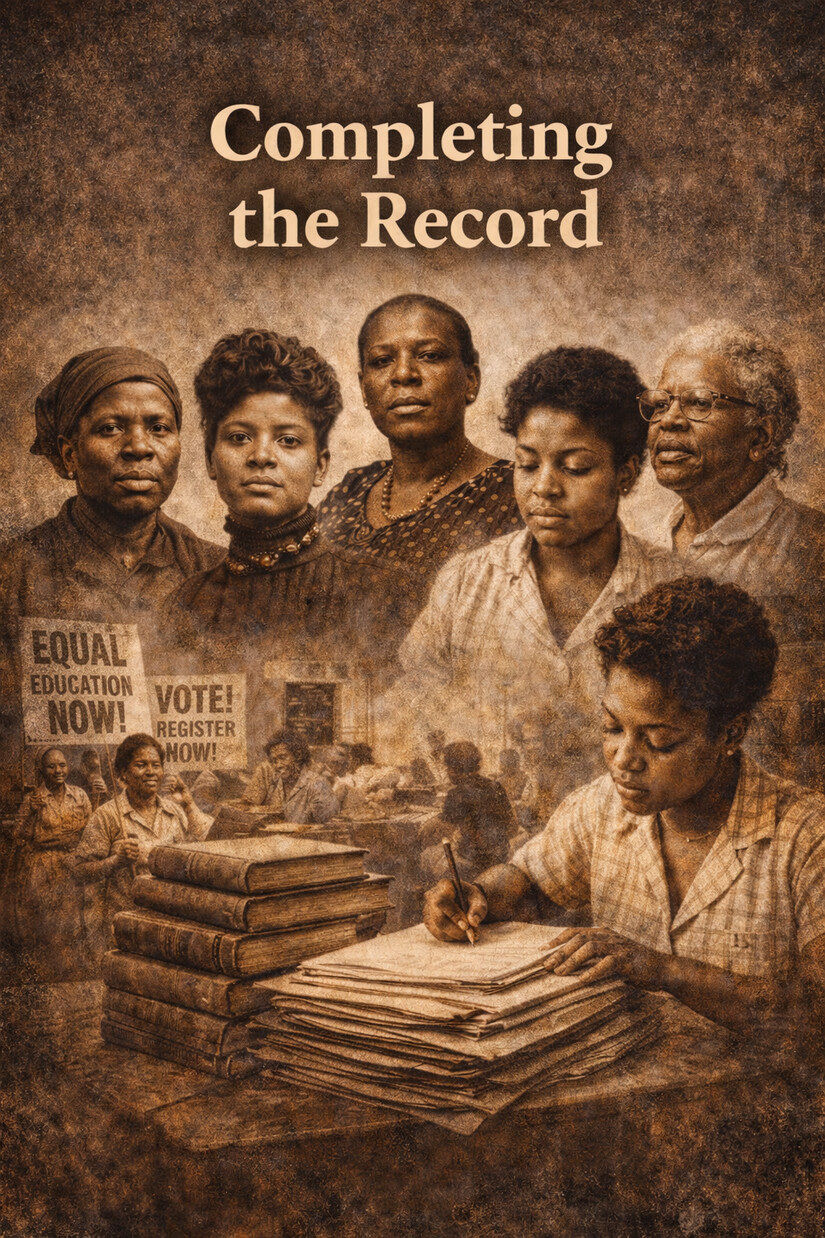

After emancipation, African American women stepped into public organizing even when formal political rights were denied to them.

They organized schools before state systems were stable. They coordinated church programs that doubled as civic forums. They formed mutual aid societies to provide sickness benefits, burial insurance, and emergency funds. They raised money for land purchases and educational facilities.

Even without the vote, they shaped civic life.

Mary Church Terrell, born to formerly enslaved parents who became entrepreneurs, emerged as a leader in the Black women’s club movement, advocating for education and civil rights nationally. Ida B. Wells conducted investigative journalism that exposed lynching as organized terror, challenging national complacency with data and evidence. These were not peripheral roles. They were central to shaping public understanding.

The club movement, organized under the motto lift as we climb, was not social. It was political infrastructure. Black women built federations that addressed public health, education reform, and anti-lynching campaigns when the state refused intervention.

They built governance where governance failed.

Ida B. Wells did not simply protest lynching. She documented it. She gathered statistics, investigated cases, and published findings that dismantled the narrative that lynching was spontaneous justice.

Her work reframed racial terror as systemic and economic.

African American women organized boycotts, raised funds for legal defense, and pressured political leaders. They were not operating at the margins of reform. They were defining its terms.

To challenge lynching was to challenge the legal system, the press, and political power simultaneously. That required strategy, not sentiment.

The civil rights movement did not move because speeches were delivered. It moved because strategy rooms functioned.

Ella Baker, often described as an organizer behind the scenes, rejected charismatic hierarchy in favor of grassroots leadership. She helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, emphasizing collective decision-making over singular leadership.

Septima Clark developed citizenship schools that taught literacy for the purpose of voter registration. Her educational strategy directly expanded political participation.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony before the Democratic National Convention was visible, but her organizing work in Mississippi was continuous and local, built on community trust.

Pauli Murray articulated legal arguments that shaped both civil rights and gender equality jurisprudence. Her legal theory influenced later Supreme Court reasoning.

These women were not assistants. They were strategists shaping movement architecture.

Yet public memory often places them in secondary position to male ministers whose speeches were televised.

Movements are remembered by who is amplified, not always by who is essential.

African American women’s labor sustained families economically across generations.

Domestic workers, agricultural laborers, teachers, nurses, and service workers carried communities through economic exclusion. For decades, domestic and agricultural labor were excluded from federal labor protections, disproportionately affecting African American women.

Yet within these constraints, women budgeted, pooled resources, invested in children’s education, and supported church and civic initiatives. They functioned as economic planners within restricted systems.

Economic survival was coordinated through women’s networks long before formal access to capital was available.

To treat this as background labor is to misunderstand its scale and impact.

African American women did not merely participate in movements. They shaped intellectual frameworks that expanded democratic thought.

Sojourner Truth challenged both racial and gender hierarchies publicly, articulating the inseparability of the two. Later scholars and activists built on analyses developed by African American women who recognized that systems of oppression intersected and reinforced one another.

Their theoretical contributions influenced legal reform, educational policy, and social justice movements globally.

Yet intellectual credit has often traveled elsewhere.

Erasure in this context is not accidental. It reflects discomfort with layered authority that challenges both racial and patriarchal structures simultaneously.

Minnesota’s African American women have long been central to organizing around housing discrimination, educational equity, labor rights, and public health.

They founded nonprofits, led church-based advocacy, organized tenant associations, and influenced local policy debates. Their work often occurred outside televised moments, within meeting rooms, classrooms, and community centers.

As with national history, local memory often highlights visible leadership while undercounting the organizing labor that sustained campaigns.

The pattern is consistent.

The minimization of African American women operates through narrative selection.

Media favors singular figures. Institutions reward hierarchical leadership. Public memory prefers simplicity.

African American women often chose collective models over charismatic dominance. That choice strengthened movements but reduced individual visibility.

Additionally, both racism and sexism shaped recognition. Leadership by African American women disrupted established hierarchies. Recognition was therefore constrained.

Erasure was not just oversight. It was structural.

Remove African American women from the record and the architecture collapses.

Churches lose organizers. Schools lose teachers. Mutual aid loses coordinators. Boycotts lose logistics. Legal challenges lose research. Voter drives lose door-to-door mobilization. Economic survival loses planners.

Movements require engineers. African American women were those engineers.

The public face of change may have been male in many instances. The operating system was often female.

To tell the truth about American democracy requires acknowledging who sustained it when the state failed.

African American women preserved community under enslavement. They built institutions during Reconstruction. They organized anti-lynching campaigns. They structured civil rights strategies. They sustained economic survival networks. They articulated democratic theory.

They were not supplementary to movements. They were structural to them.

If democracy expanded in the United States, it did so because African American women forced it to confront its contradictions and supplied the infrastructure to survive the confrontation.

The record must reflect that.

Not as tribute.

Not as correction alone.

But as fact.