Image

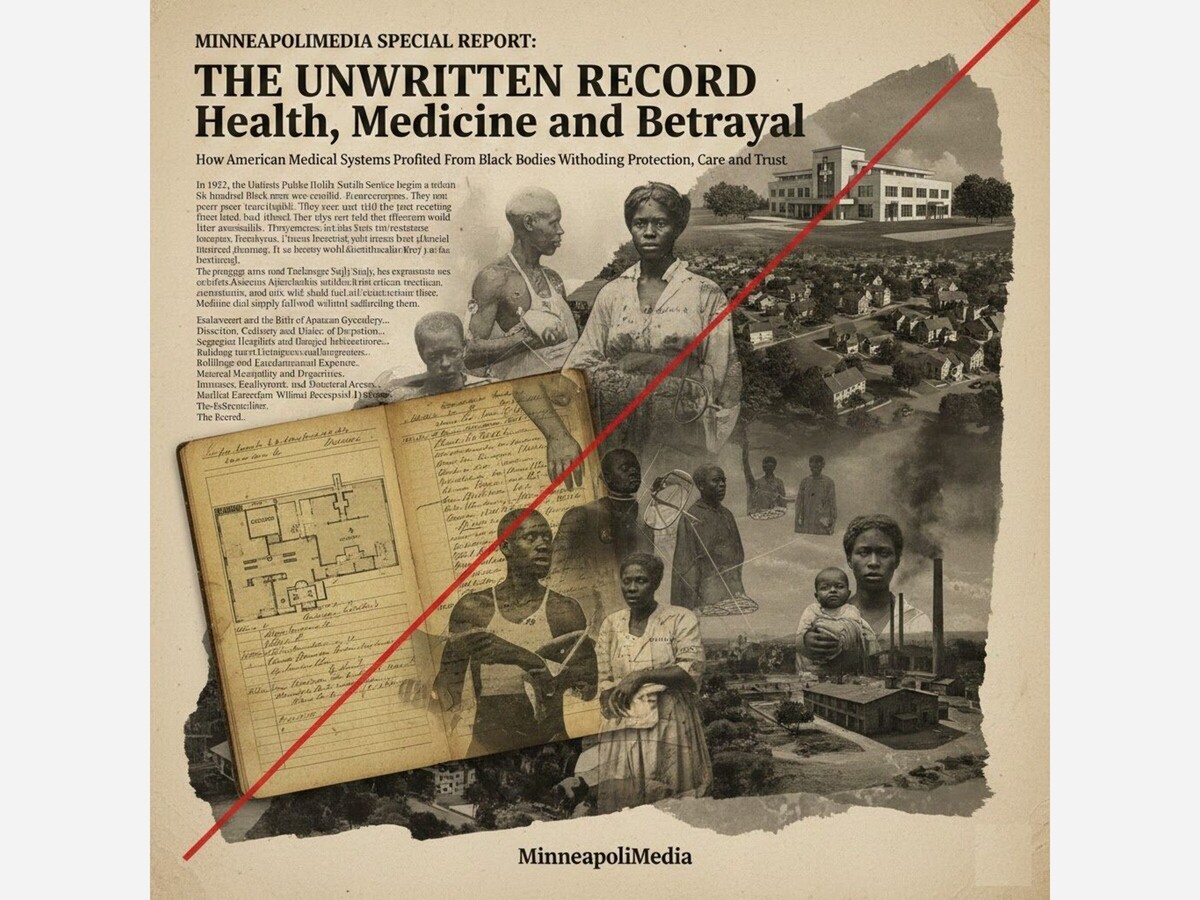

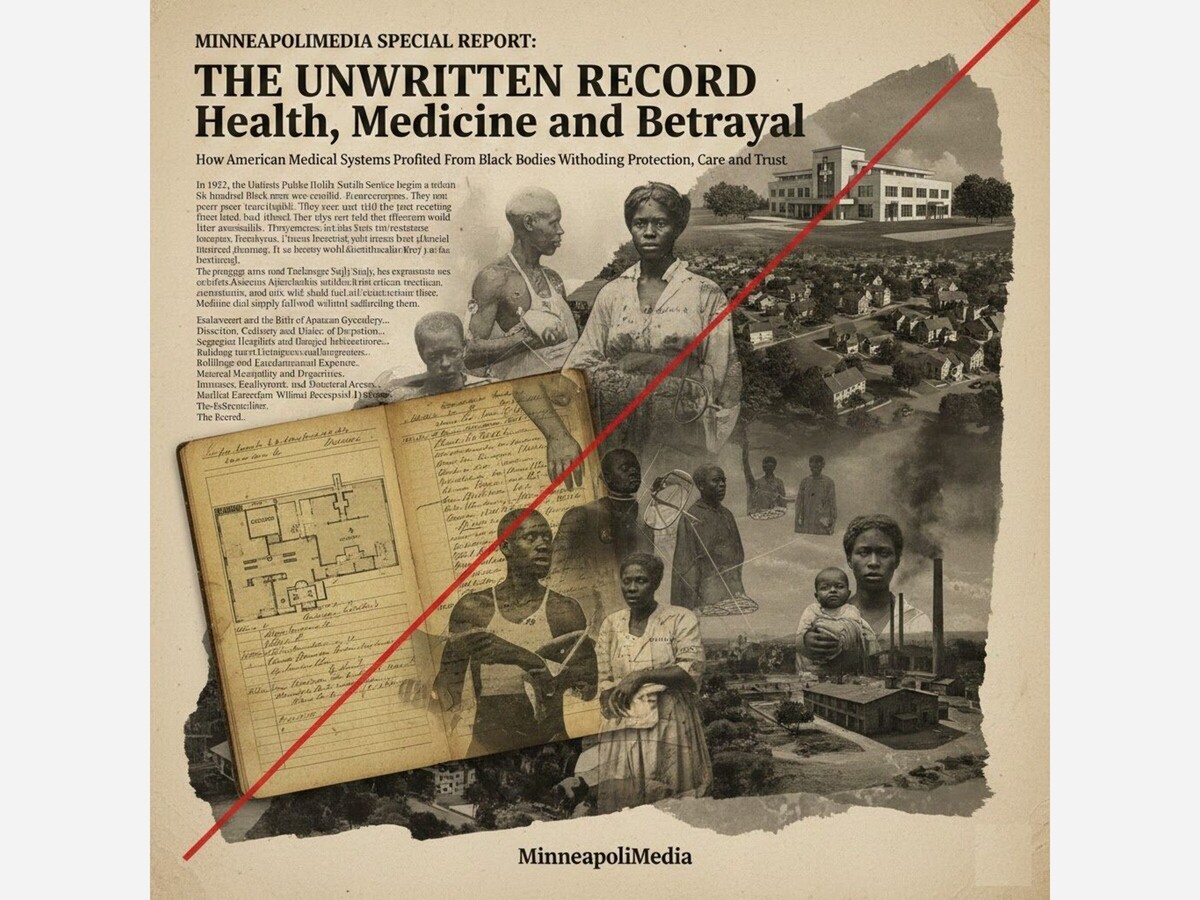

How American Medical Systems Profited From Black Bodies While Withholding Protection, Care, and Trust

In 1932, the United States Public Health Service began a study in Macon County, Alabama. Six hundred Black men were enrolled. Many were poor sharecroppers. They were told they were receiving treatment for “bad blood.”

They were not told they had syphilis.

They were not told that effective treatment would later become available.

They were not told that the study would continue for forty years.

This program, now known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, has become shorthand for medical betrayal.

But Tuskegee was not anomaly.

It was exposure.

It revealed a deeper pattern in American medicine: African American bodies were often treated as sites of experimentation, extraction, and risk while simultaneously being denied full access to protection, preventive care, and structural investment.

Medicine did not simply fail Black communities.

It often studied them without safeguarding them.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Dr. J. Marion Sims conducted surgical experiments on enslaved Black women in Alabama. His procedures aimed to repair vesicovaginal fistulas, a painful childbirth injury.

Historical records indicate that these surgeries were performed repeatedly on women such as Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey without anesthesia.

Anesthesia existed at the time. It was not used.

Sims justified this practice under prevailing racist beliefs that Black people experienced pain differently.

The women had no legal capacity to refuse. They were enslaved.

Modern gynecology benefited from these experiments. Medical textbooks long credited Sims as a pioneering figure.

Only recently have broader public conversations acknowledged the coercive and exploitative conditions under which that knowledge was produced.

The field advanced.

The subjects were unprotected.

This pattern matters.

It shows that medical innovation and racial hierarchy were not separate tracks.

They intersected.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, medical schools required cadavers for anatomical study. In many cities, bodies of poor and marginalized individuals were disproportionately used for dissection.

African American cemeteries were often targeted for grave robbing. In some cases, bodies were taken without consent to meet demand for anatomical training.

The practice was not openly acknowledged in mainstream institutions. It was quietly normalized.

The extraction of Black bodies for scientific education occurred alongside exclusion of Black physicians from professional networks and hospital privileges.

Knowledge accumulation and racial exclusion coexisted.

Medicine advanced. Access did not.

When penicillin became a recognized treatment for syphilis in the 1940s, participants in the Tuskegee study were not informed. Treatment was withheld in order to observe the progression of the disease.

The study continued until 1972, when it was exposed through press reporting.

Public reaction was intense.

The federal government later issued an apology. Bioethics reforms were strengthened.

But the damage extended beyond the participants.

Tuskegee became a symbol of medical mistrust in African American communities.

When institutions demonstrate willingness to deceive in pursuit of data, trust erodes across generations.

Mistrust is not irrational in a vacuum.

It is shaped by record.

Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many hospitals in the United States were segregated. African American patients were often relegated to separate wards, received inferior facilities, or were denied admission entirely.

The Hill-Burton Act of 1946 funded hospital construction across the country. Many facilities receiving federal funds operated segregated wings or excluded Black patients outright.

The language of separate but equal persisted within medical infrastructure.

Separate was not equal.

African American communities frequently relied on underfunded hospitals or Black-run institutions that operated with limited resources but high commitment.

Access to modern equipment, specialty care, and surgical innovation was uneven.

Health outcomes reflected structural investment.

Housing policy intersects with health.

Redlined neighborhoods were often located near industrial zones, highways, and waste sites. Residents experienced higher exposure to pollution, lead paint, and environmental toxins.

Asthma rates, infant mortality rates, and chronic disease prevalence correlate with environmental conditions shaped by housing segregation.

When neighborhoods are classified as hazardous and denied investment, health infrastructure follows that classification.

Food deserts emerge where grocery investment is withheld. Clinics are scarce where capital is scarce.

Health disparities are not spontaneous.

They follow policy.

In the modern era, African American women in the United States experience significantly higher maternal mortality rates compared to white women.

Research has shown that these disparities persist even when controlling for income and education.

This suggests that structural bias within healthcare delivery remains active.

Historical patterns of medical dismissal, underestimation of pain, and implicit bias contribute to differential outcomes.

The past is not fully past.

When history includes experimentation without consent and care without equality, contemporary trust gaps and outcome disparities must be understood in that context.

Minnesota frequently ranks highly in overall healthcare metrics. Yet racial disparities in maternal health, infant mortality, and chronic disease outcomes persist within the state.

Public reports often describe these as gaps.

The word gap describes distance. It does not describe origin.

Segregated housing patterns, income disparities rooted in labor exclusion, and differential access to preventive care shape outcomes.

The state’s reputation for overall excellence can obscure internal inequality.

Health systems may appear neutral while reproducing uneven impact.

In the United States, access to healthcare has often been tied to employment.

Given the historical exclusion of African Americans from certain protected labor sectors, employer-based insurance has not always been equitably distributed.

When agricultural and domestic workers were excluded from New Deal labor protections, they were also excluded from employer-based stability.

Later, when industrial jobs declined, communities that had finally secured stable employment lost not only wages but health coverage.

Policy architecture links labor history to medical access.

Throughout American history, African American bodies have been sites of medical innovation, yet communities have not consistently received reciprocal protection.

From forced experimentation under slavery to unequal hospital infrastructure to disparities in research inclusion and access to cutting-edge treatment, the pattern reveals imbalance.

Participation in clinical trials has often been limited by mistrust rooted in history.

At the same time, representation in medical leadership remains uneven.

Knowledge production and care delivery are not equally distributed.

Health is not merely biology. It is policy.

Enslavement shaped trauma and labor conditions.

Segregation shaped hospital access.

Redlining shaped environmental exposure.

Labor exclusion shaped insurance access.

Medical experimentation shaped trust.

The result is measurable disparity.

But disparity is not destiny. It is documentation of policy impact.

To describe African American mistrust of medical systems as irrational ignores history.

To describe health disparities as unfortunate ignores architecture.

The record shows repeated moments where medicine advanced while protection lagged for African Americans.

It also shows resistance.

Black physicians built hospitals when excluded. Community clinics formed in neglected neighborhoods. Public health advocates demanded inclusion. Policy reforms emerged from exposure of abuse.

The story is not one of passive victimhood.

It is one of structural betrayal met with organized response.

Medicine, like democracy, reflects the moral choices embedded within it.

If health systems are to be trusted, they must reckon with the record that produced distrust.

That reckoning belongs in the archive.

And it belongs in the future.