Image

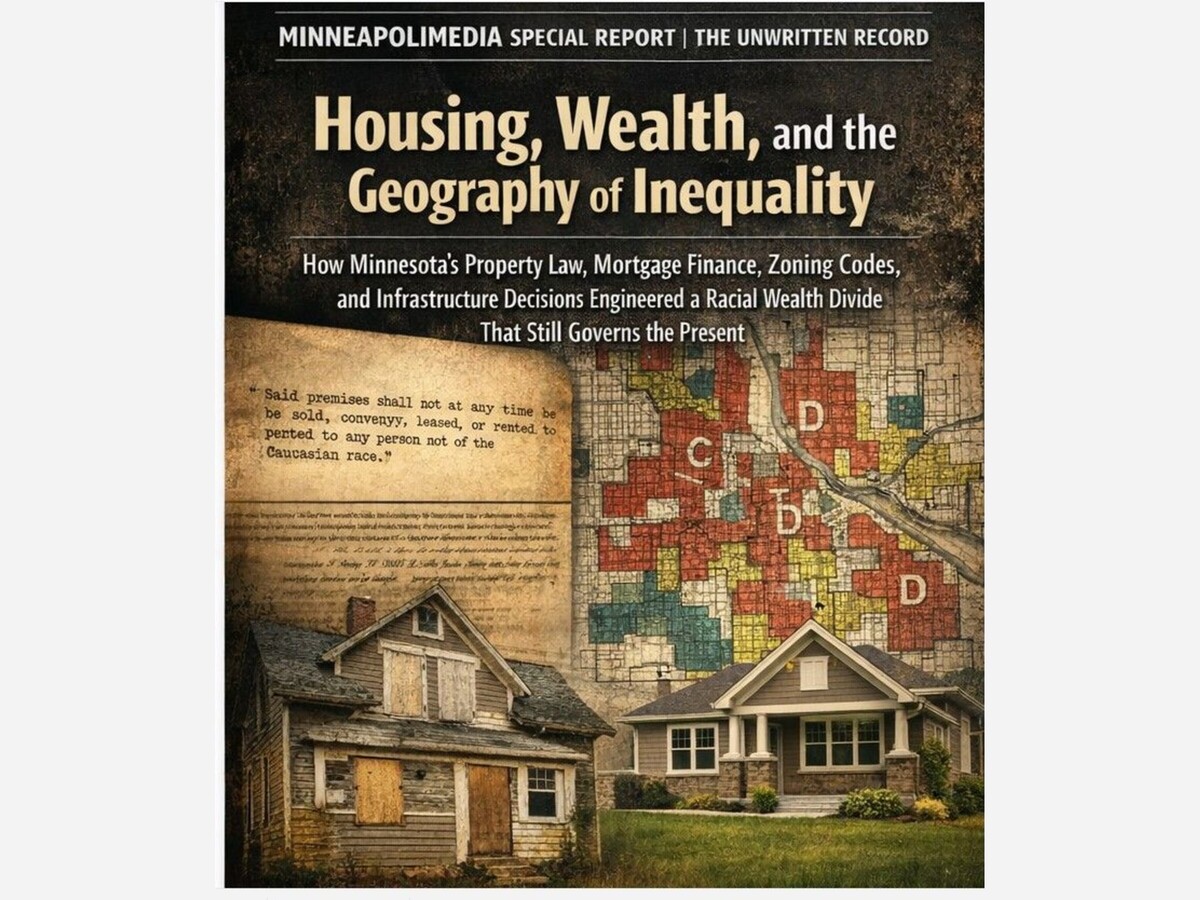

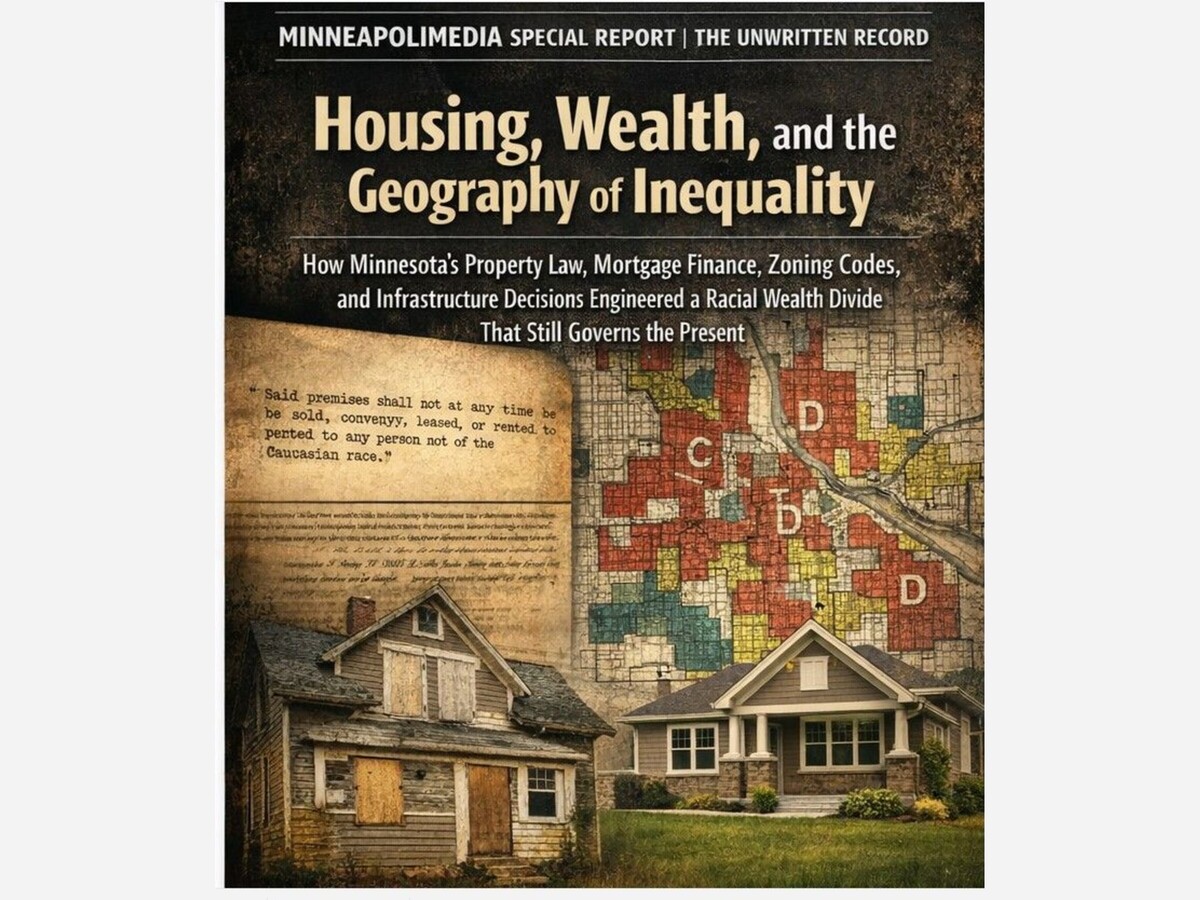

In the quiet of a Hennepin County records office, beneath layers of aging parchment and recorded plats, lies a sentence that reshaped Minnesota’s economic future.

“Said premises shall not at any time be sold, conveyed, leased, or rented to any person not of the Caucasian race.”

It was written without hesitation. It was signed without shame. It was recorded without objection.

The clause did not merely describe prejudice. It structured opportunity.

Between the early twentieth century and the mid-1950s, tens of thousands of such covenants were filed across Minneapolis and its surrounding suburbs. Researchers working through the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice project have identified more than 30,000 racially restrictive covenants in Hennepin County alone. Entire blocks were bound by identical language. Entire subdivisions were designed to prevent Black ownership before the first foundation was poured.

These covenants were not symbolic artifacts. They were instruments of market design. They determined who could purchase appreciating property during the century when homeownership became the primary vehicle for middle class wealth in the United States.

Minnesota’s racial wealth gap did not emerge from cultural deficiency or market accident. It was constructed through law, reinforced through finance, and protected through policy.

Housing in Minnesota was not merely shelter. It was the engine of generational wealth. The boundaries drawn on deeds and maps determined who would accumulate equity, who would leverage collateral, who would pass inheritance, and who would begin each generation at zero.

To understand wealth in Minnesota, one must read the deed.

To understand the deed, one must read the law.

The covenant system in Minnesota did not exist in isolation. It was reinforced by federal design.

The Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. HOLC surveyors mapped American cities between 1935 and 1940, including Minneapolis. Neighborhoods were graded from A to D. Areas graded D were shaded red and labeled hazardous.

The written area descriptions accompanying the Minneapolis maps frequently referenced the presence of “inharmonious racial groups” as a risk factor. In federal underwriting language of the era, racial heterogeneity was treated as financial instability.

Even when local lenders did not cite HOLC grades explicitly, the federal classification system shaped lending culture. Credit followed perceived stability. Stability was equated with racial homogeneity.

The Federal Housing Administration deepened this framework. The 1938 FHA Underwriting Manual stated that if a neighborhood was to retain stability, properties must continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. The manual encouraged the use of restrictive covenants as a tool for protecting property value.

In Minnesota, suburban developments expanding south and west of Minneapolis during the 1940s and 1950s depended heavily on FHA insured mortgages. FHA insurance reduced down payments and extended repayment terms, allowing white families to purchase homes at scale.

FHA backing required predictability. Developers complied. Lenders complied. Subdivisions were platted with racial restrictions embedded at inception.

The federal government did not simply tolerate segregation. It incentivized it.

Suburban equity accumulated. Urban exclusion hardened.

In 1926, the United States Supreme Court upheld the enforceability of racially restrictive covenants in Corrigan v. Buckley. Minnesota courts enforced such covenants for more than two decades.

In 1948, Shelley v. Kraemer held that judicial enforcement of racial covenants constituted state action and violated the Equal Protection Clause. Courts could no longer enforce them.

But by 1948, the allocation had already occurred.

White families had secured FHA insured mortgages in appreciating suburban neighborhoods. Black families had been excluded. The wealth engine was running.

Shelley ended enforcement. It did not undo accumulation.

The absence of enforcement did not redistribute equity already gained.

To understand the magnitude of this design, one must examine compounding.

In 1950, a modest home in a Minneapolis suburb might sell for $10,000. With FHA insurance, a white family could purchase with limited down payment and fixed interest.

If that property appreciated at an average annual rate of 4 percent over 70 years, its value would exceed $160,000 by 2020. In many desirable Twin Cities suburbs, appreciation rates exceeded that conservative estimate.

Equity could be refinanced. It could finance education. It could serve as collateral for business loans. It could be inherited.

Now consider a Black family in 1950 excluded from that suburb due to covenant language and lending practices, renting in a redlined urban neighborhood.

No equity accumulates. No collateral exists. No inheritance transfers.

Across two generations, the wealth divergence expands exponentially.

This is not rhetorical framing. It is compound interest.

Minnesota’s racial wealth gap is not philosophical. It is mathematical.

After explicit racial zoning was prohibited, Minnesota municipalities turned to economic zoning.

Single family zoning, minimum lot sizes, and density restrictions became dominant tools of suburban expansion in the postwar era. Suburbs such as Edina, Bloomington, and portions of Anoka and Dakota counties adopted zoning codes that limited multifamily construction.

The language was race neutral. The effect was exclusionary.

When wealth was already racially stratified due to mortgage exclusion and covenant enforcement, zoning reinforced separation.

Suburban tax bases grew. Urban tax bases stagnated.

Segregation adapted to new vocabulary.

The Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul was the center of Black economic and civic life in mid century Minnesota. Homeowners, small businesses, churches, and social institutions formed a concentrated economic network.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Interstate 94 was routed directly through Rondo. More than 600 families were displaced. Businesses were demolished. Homes were acquired through eminent domain.

Compensation reflected assessed value, not appreciation trajectory.

Homeowners uprooted in mid century lost not only shelter but generational equity potential. At the same time, suburban homeowners in expanding communities experienced steady appreciation.

One population experienced compounding. The other experienced interruption.

Infrastructure was not neutral. It redistributed opportunity.

Homeownership remains the primary asset for middle class households. In Minnesota, white homeownership rates have consistently exceeded Black homeownership rates by substantial margins.

According to recent Census Bureau data, white homeownership in Minnesota approaches or exceeds 70 percent. Black homeownership lags far behind.

Homeownership disparity reflects decades of cumulative exclusion.

The wealth gap mirrors that history. Federal Reserve data consistently shows that Minnesota has one of the largest racial wealth gaps in the nation.

White median household wealth in Minnesota measures in multiples of Black median household wealth.

The difference is not mysterious.

It reflects who entered appreciating markets in the 1940s and 1950s and who was denied entry.

The housing bubble of the early 2000s created fragile gains in some historically excluded neighborhoods. Subprime lending expanded rapidly.

National research has shown that African American borrowers were disproportionately steered into high cost loans even when qualifying for prime rates.

In North Minneapolis, foreclosure filings surged between 2008 and 2012. Entire blocks experienced concentrated vacancies. Property values fell. Investor purchases increased. Owner occupancy declined.

Communities historically excluded from stable appreciation were more vulnerable to financial collapse.

The foreclosure crisis widened existing disparity.

It did not create it.

Recent research has demonstrated that homes in majority Black neighborhoods are often appraised at lower values than comparable homes in majority white neighborhoods.

Appraisal systems rely on comparable sales. If a neighborhood was historically redlined and disinvested, comparables reflect that history.

Lower appraisal constrains refinancing. It limits equity extraction. It slows wealth growth.

The red line drawn in the 1930s may not appear on official maps today, but it remains embedded in valuation patterns.

History lingers in spreadsheets.

Minnesota schools are funded in part through property taxes.

Higher property values produce stronger local tax bases. Lower property values produce weaker ones.

When neighborhoods are historically excluded from appreciation, the tax base reflects that exclusion.

School funding disparities follow housing geography.

Educational outcomes influence income. Income influences wealth. Wealth influences political voice.

Housing is not a peripheral policy domain. It is the substrate upon which opportunity rests.

Housing intersects with every chapter in this series.

Migration patterns shaped neighborhood boundaries. Labor market discrimination influenced mortgage qualification. Education funding followed property values. Policing concentrated in segregated areas. Health outcomes tracked environmental exposure shaped by zoning and disinvestment.

The geography of inequality in Minnesota was not incidental. It was engineered.

Through covenant language.

Through federal mortgage insurance standards.

Through zoning codes.

Through highway placement.

Through lending practices.

Through appraisal methodology.

The deed recorded in Hennepin County in 1941 was not an anomaly. It was a node in a system.

The evidence is recorded in county archives, federal maps, zoning ordinances, and wealth data.

Minnesota’s racial wealth gap is among the largest in the United States. That reality does not arise from accident. It arises from accumulation.

When one population is systematically included in appreciating property markets and another is systematically excluded, disparity compounds.

The red lines of the twentieth century shaped the balance sheets of the twenty first.

Housing policy was wealth policy. Wealth policy became opportunity policy. Opportunity policy shaped democracy.

Every chapter in this series converges here.

The covenant recorded in 1941 was not merely a sentence. It was a decision about who would belong to the future.

Minnesota’s prosperity narrative is incomplete without this record.

The land remembers. The ledger remains. The consequences continue.