Image

How Political Power in Minnesota Was Structured, Restricted, Expanded, and Engineered — and Why Control of the Vote Determined Every Other Chapter in This Record

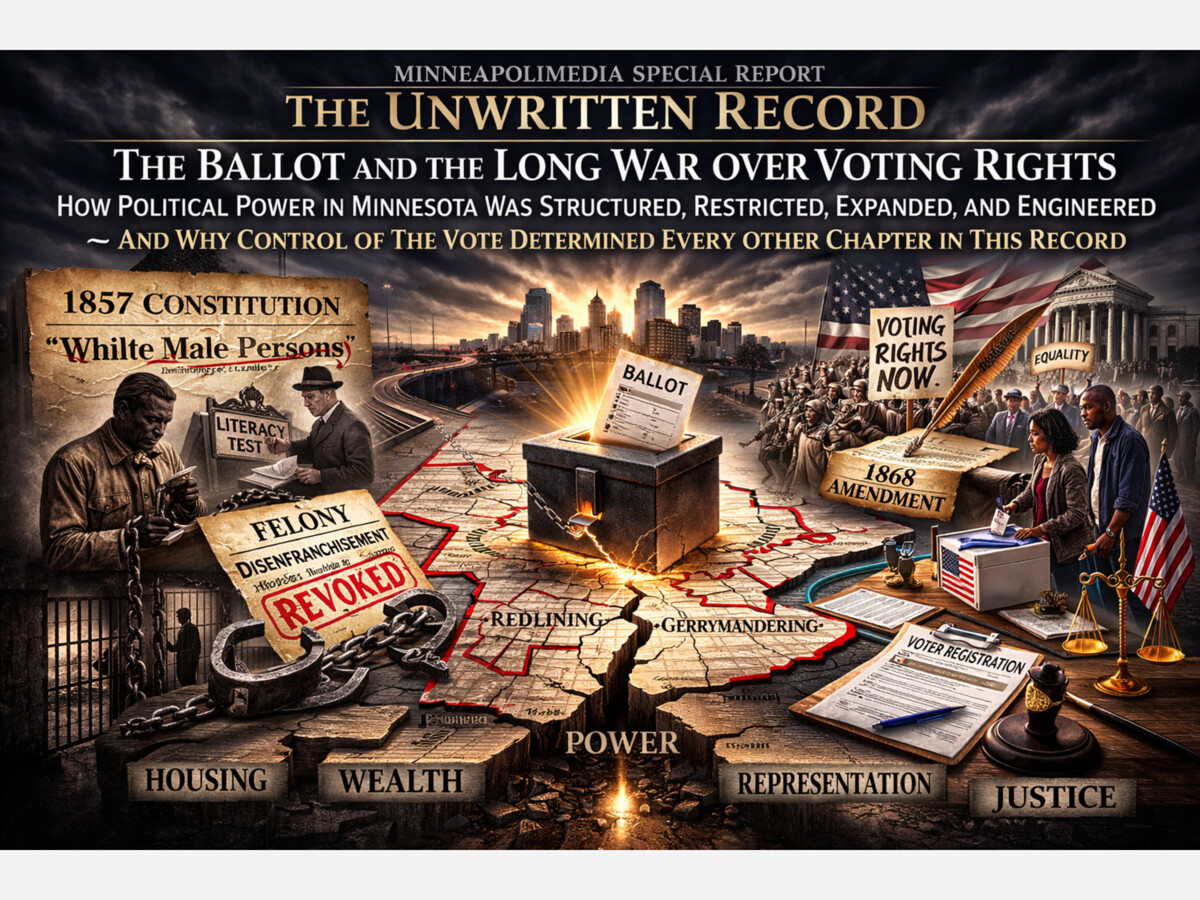

When Minnesota drafted its Constitution in 1857, Article VII, Section 1, declared that the right to vote belonged to “white male persons” who were citizens of the United States, at least twenty one years of age, and residents of the state for a specified duration.

The word white was not implied. It was written.

At the moment of statehood, political belonging in Minnesota was racially bounded by constitutional text.

This was the same year the United States Supreme Court decided Dred Scott v. Sandford, holding that persons of African descent could not be citizens of the United States. Minnesota’s suffrage clause did not exist in isolation. It aligned with a national racial order.

The right to vote is the right to allocate power.

From the beginning, that allocation excluded Black residents.

After the Civil War, Minnesota confronted the question of Black suffrage directly.

In 1867, voters rejected a proposed amendment to remove the word white from the suffrage clause.

The following year, in 1868, the amendment passed. The racial qualifier was struck from the Constitution.

Minnesota often receives credit for this early expansion, preceding ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

But the record requires precision.

In 1860, African Americans represented a small fraction of Minnesota’s population. Concentration in limited urban areas and economic exclusion meant that formal voting rights did not immediately translate into proportional influence.

Legal inclusion is not identical to political parity.

The Fifteenth Amendment prohibited denial of the vote on the basis of race. Minnesota complied in language. It did not create a southern style poll tax regime. It did not adopt literacy tests.

Yet suffrage remained conditioned on citizenship, residency, and criminal status.

Power was expanded, but it was not equalized.

While Black male suffrage was formally recognized in 1868, Native Americans in Minnesota faced different barriers.

Full citizenship for Native Americans was not broadly recognized until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Even after that statute, practical voting barriers persisted.

Local registration practices, geographic isolation, and inconsistent enforcement shaped participation.

The franchise expanded unevenly across communities.

The ballot in Minnesota has always been mediated by status.

Minnesota law has long linked criminal conviction to loss of civil rights.

Under Minnesota Statutes Section 609.165, individuals convicted of felonies lost the right to vote until they completed all terms of their sentence, including probation and supervised release.

For much of the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries, this meant that thousands of Minnesotans living in the community but still under supervision could not vote.

To understand the structural effect, consider scale.

Minnesota’s prison population grew significantly from the 1980s onward. While Minnesota’s incarceration rate has historically been lower than some states, racial disparities within that system have been substantial.

African Americans represent a significantly higher percentage of the incarcerated population than their percentage of the state’s total population.

When incarceration increases in certain communities, and conviction triggers disenfranchisement, political power contracts in those communities.

This is not symbolic.

It alters electorate composition.

In 2023, Minnesota restored voting rights to individuals upon release from incarceration rather than completion of probation or parole.

The reform immediately expanded the electorate by tens of thousands of residents.

For decades prior, those residents were excluded.

Housing segregation concentrated poverty.

Policing concentrated enforcement.

Enforcement concentrated conviction.

Conviction triggered disenfranchisement.

The loop is structural.

Voting is not only about who casts a ballot. It is about how ballots are translated into legislative power.

Minnesota redraws legislative and congressional districts every ten years following the census.

When the legislature and governor cannot agree on maps, courts intervene. Minnesota has a long history of judicially crafted redistricting plans.

District boundaries determine representation density.

If a community is concentrated in one district, it may achieve influence. If it is divided across multiple districts, its voting strength can be diluted.

North Minneapolis and portions of St. Paul have historically housed concentrated African American populations due to housing segregation patterns documented in the housing chapter.

When district lines are drawn, the question becomes whether those populations are consolidated or fragmented.

Housing geography shapes political geography.

The red line on a 1930s map can influence the line drawn in a 2020 redistricting plan.

Representation is mathematical.

Population concentration multiplied by district design equals political weight.

Minnesota is often cited as having one of the highest voter turnout rates in the nation.

Same day registration, early voting options, and relatively accessible administrative processes have contributed to participation.

Yet administrative structure matters at the margins.

Identification requirements, registration deadlines, polling site distribution, and language access can influence turnout among economically vulnerable populations.

Participation disparities correlate strongly with income and educational attainment.

Communities with lower wealth levels vote at lower rates nationally and within Minnesota.

This is not evidence of apathy. It reflects time constraints, housing instability, transportation access, and civic disengagement shaped by structural exclusion.

When wealth is unevenly distributed due to housing policy, turnout reflects that inequality.

Political science research consistently shows that income and wealth are strong predictors of voter turnout.

In Minnesota, turnout rates remain high overall, but disparities persist between high income suburban communities and lower income urban neighborhoods.

If wealth accumulates in FHA backed suburbs and stagnates in redlined urban zones, participation patterns follow.

Wealth stabilizes housing. Stable housing stabilizes registration. Stable employment increases civic engagement.

The feedback loop becomes clear.

Housing policy influences wealth.

Wealth influences turnout.

Turnout influences representation.

Representation influences housing policy.

The ballot is not separate from land. It governs it.

Consider the system in sequence.

The 1857 Constitution restricted suffrage to white men.

The 1868 amendment expanded formal inclusion.

Criminal disenfranchisement narrowed the electorate for those convicted.

Disparities in policing increased conviction rates in specific communities.

Housing segregation concentrated poverty and enforcement.

Disenfranchisement reduced representation in those communities.

Reduced representation influenced housing, zoning, and sentencing policy.

The structure reinforces itself.

Political power determines budget allocations, infrastructure routing, and regulatory frameworks.

When certain communities possess diminished voting strength, their influence over those decisions shrinks.

This is not accusation. It is architecture.

Minnesota’s suffrage history includes early expansion and modern reform. It also includes foundational exclusion and structural narrowing.

The ballot has been amended, litigated, restored, and contested.

But the core truth remains.

Who votes determines who writes the rules.

The legislature that approved zoning codes was elected.

The officials who authorized Interstate 94 were elected.

The statutes governing felony disenfranchisement were enacted by elected representatives.

The reforms restoring voting rights were passed by elected officials.

The ballot is the hinge.

The power to vote is the power to allocate law.

Minnesota’s constitutional text once restricted that power by race.

Amendments expanded it.

Criminal statutes narrowed it again.

Modern reforms reopened it.

Control of the ballot shapes control of land.

Control of land shapes control of wealth.

Control of wealth shapes opportunity.

Every chapter in this record converges at the polling place.

The covenant determined who could buy the home.

The ballot determined who could write the zoning code.

The highway cut through Rondo.

The legislature authorized its path.

The foreclosure crisis devastated neighborhoods.

Financial regulation was written by elected officials.

The ballot is not ceremonial. It is structural.

Who votes decides who decides.

And who decides shapes Minnesota’s future.