Image

Minnesota is often taught as an exception.

In the national imagination, it occupies a moral middle ground. A northern state. A free state. A place without plantations or formal enslavement on the scale associated with the South. This framing has endured for generations, reinforced by textbooks, civic narratives, and local histories that present Minnesota as neutral ground in the American racial story.

The record does not support this claim.

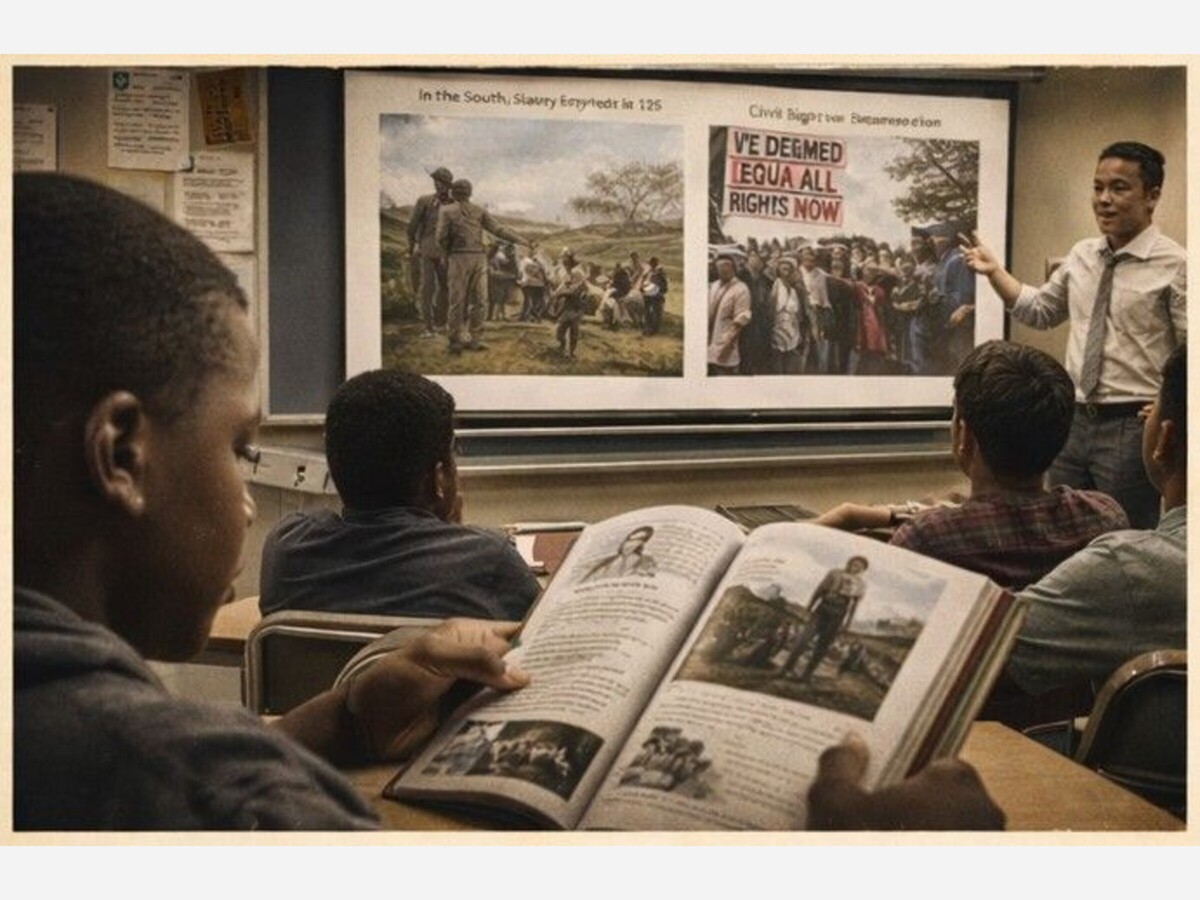

African Americans were present in Minnesota before statehood. They labored, served, organized, resisted, and endured exclusion long before Minnesota entered the Union in 1858. What distinguishes Minnesota is not absence, but silence. The state did not escape the architecture of erasure. It refined it.

African American presence in Minnesota predates statehood by decades. Enslaved people were brought into the region by military officers, traders, and settlers despite federal prohibitions under the Northwest Ordinance. The most widely documented example is the enslavement of Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson Scott at Fort Snelling, then a federal outpost in the Wisconsin Territory.

Their residence on free soil did not result in freedom. When Dred Scott later sued for his liberty, the United States Supreme Court ruled that people of African descent could not be citizens and had no standing in federal court. The decision did not merely deny Scott his freedom. It nationalized erasure by declaring African Americans outside the constitutional order itself.

Minnesota’s role in that history is often treated as incidental. It was not.

The territory enforced federal authority, benefited from enslaved labor, and then retreated into silence when the legal consequences of that history became inconvenient.

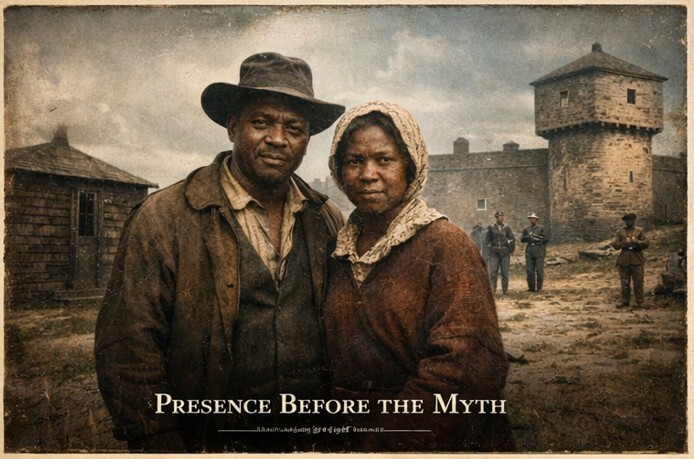

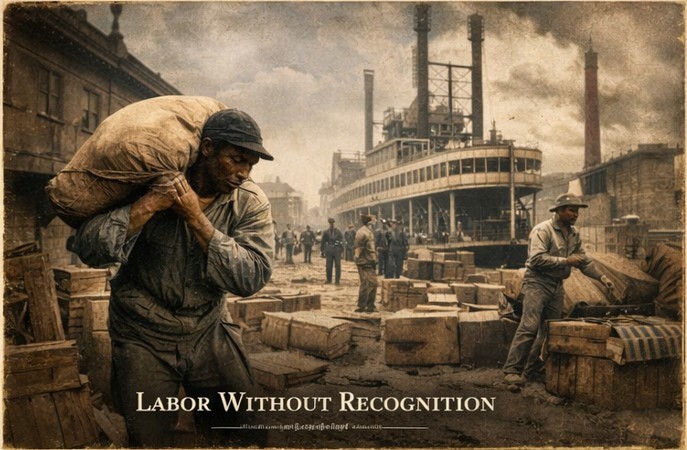

African Americans in early Minnesota performed essential labor. They worked as teamsters, cooks, laundresses, farmhands, river workers, and domestic laborers. They moved goods along the Mississippi River. They supported military posts. They sustained households whose names would later define towns, streets, and institutions.

This labor rarely appears in official histories.

Early Minnesota narratives celebrate pioneers, traders, and industrialists while treating labor as an abstract force rather than human contribution. When African American laborers appear at all, they are unnamed and uncontextualized. Their work is acknowledged without their presence.

Erasure here functioned through attribution. Economic development was credited upward. Labor was rendered invisible.

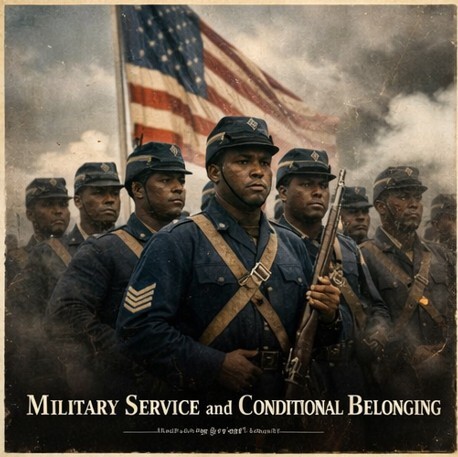

African Americans served in the United States military from Minnesota during the Civil War, most notably in the United States Colored Troops. Service was framed as proof of loyalty, sacrifice, and worthiness of citizenship.

Yet military service did not translate into full belonging.

Veterans returned to communities where housing was restricted, employment was limited, and political participation remained precarious. Their uniforms did not shield them from discrimination. Their service did not grant them inclusion in the state’s self-image.

Minnesota celebrated its contribution to the Union. It did not fully acknowledge who bore the cost of that contribution.

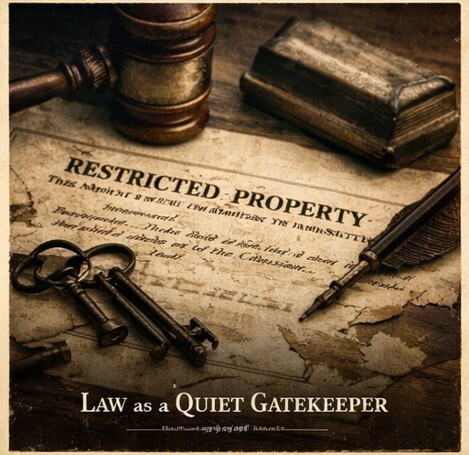

Minnesota did not rely on the explicit racial statutes common in southern states. Its exclusions were quieter and often more durable.

Early state laws restricted voting, property ownership, and access to public institutions through mechanisms that appeared neutral on paper but discriminatory in practice. Residency requirements, character assessments, and economic thresholds functioned as filters. Racial exclusion was enforced through discretion rather than declaration.

This approach produced plausible deniability. Discrimination could be explained as administrative necessity rather than racial intent.

The result was the same. African Americans were systematically excluded from full participation in civic life while the state maintained its image of fairness.

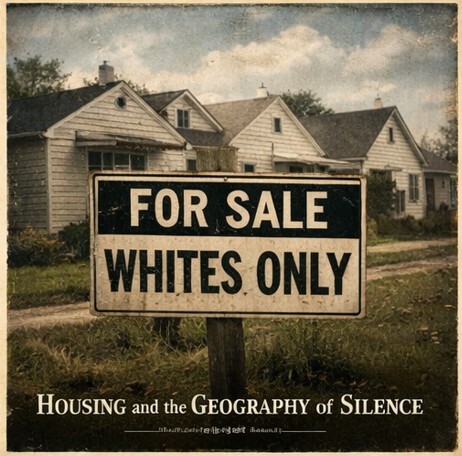

Perhaps nowhere is Minnesota’s erasure more visible than in housing.

Restrictive covenants, redlining, informal steering, and lending discrimination shaped the geography of cities and suburbs across the state. African Americans were confined to specific neighborhoods, denied mortgages, and blocked from wealth accumulation through property ownership.

These practices were not anomalies. They were coordinated through real estate boards, financial institutions, and local governments.

The impact was generational.

Neighborhood segregation influenced school funding, employment access, health outcomes, and political power. When disparities emerged, they were framed as natural outcomes of preference or economics rather than policy.

The state taught itself that segregation happened elsewhere.

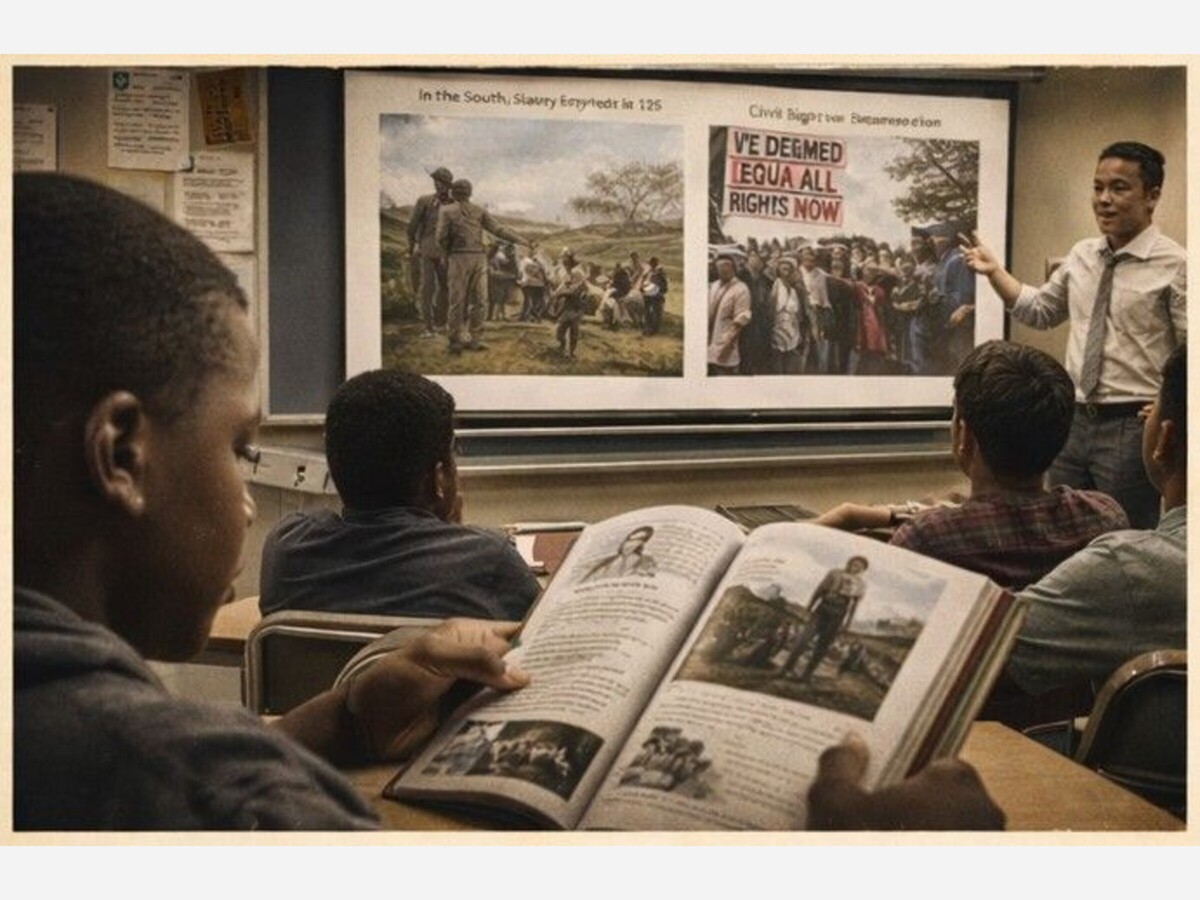

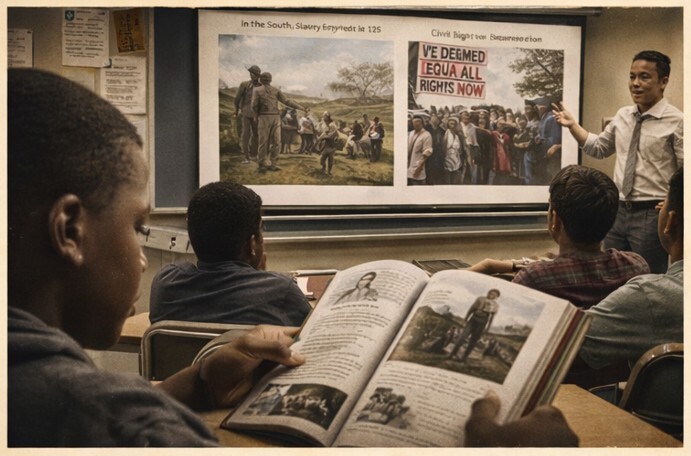

Minnesota prides itself on education. Yet its curricula have long minimized the state’s own racial history.

Students learn about enslavement as a southern institution, civil rights as a national struggle, and inequality as an imported problem. Minnesota’s role is often reduced to moral alignment rather than material participation.

African American presence is introduced late, briefly, and often disconnected from place.

This educational structure denies continuity. It suggests that African Americans arrived in Minnesota recently, fully formed by struggles elsewhere, rather than as participants in the state’s formation. It preserves the illusion that racial inequality is external to Minnesota’s identity.

Education here does not lie outright. It omits strategically.

Erasure in Minnesota did not rely on spectacle. It relied on restraint.

By avoiding explicit racial language, the state insulated itself from critique. By celebrating progress without reckoning, it avoided accountability. By emphasizing neutrality, it absolved itself of responsibility.

This approach shaped public policy and civic culture. It influenced how disparities were discussed, how remedies were evaluated, and how urgency was assigned.

When inequality was observed, it appeared uncaused.

The Minnesota we do not teach continues to govern the present.

Disparities in housing, education, health, and criminal justice did not emerge spontaneously. They are the accumulated outcome of decisions made invisible by narrative design.

To confront this history is not to indict individual Minnesotans. It is to correct the record that informs governance.

A democracy cannot address problems it refuses to name. A state cannot repair what it claims never happened.

African Americans did not arrive in Minnesota after the story began. They were present before it was written.

They labored without recognition. They served without inclusion. They endured laws that excluded without declaring exclusion. They built lives in a state that preferred not to remember them.

To teach Minnesota honestly is not to diminish it. It is to take it seriously.

History is not neutral. It is curated.

The Minnesota we do not teach is not hidden. It has simply been left out.

This series exists to put it back where it belongs.

At the center of the record.