Image

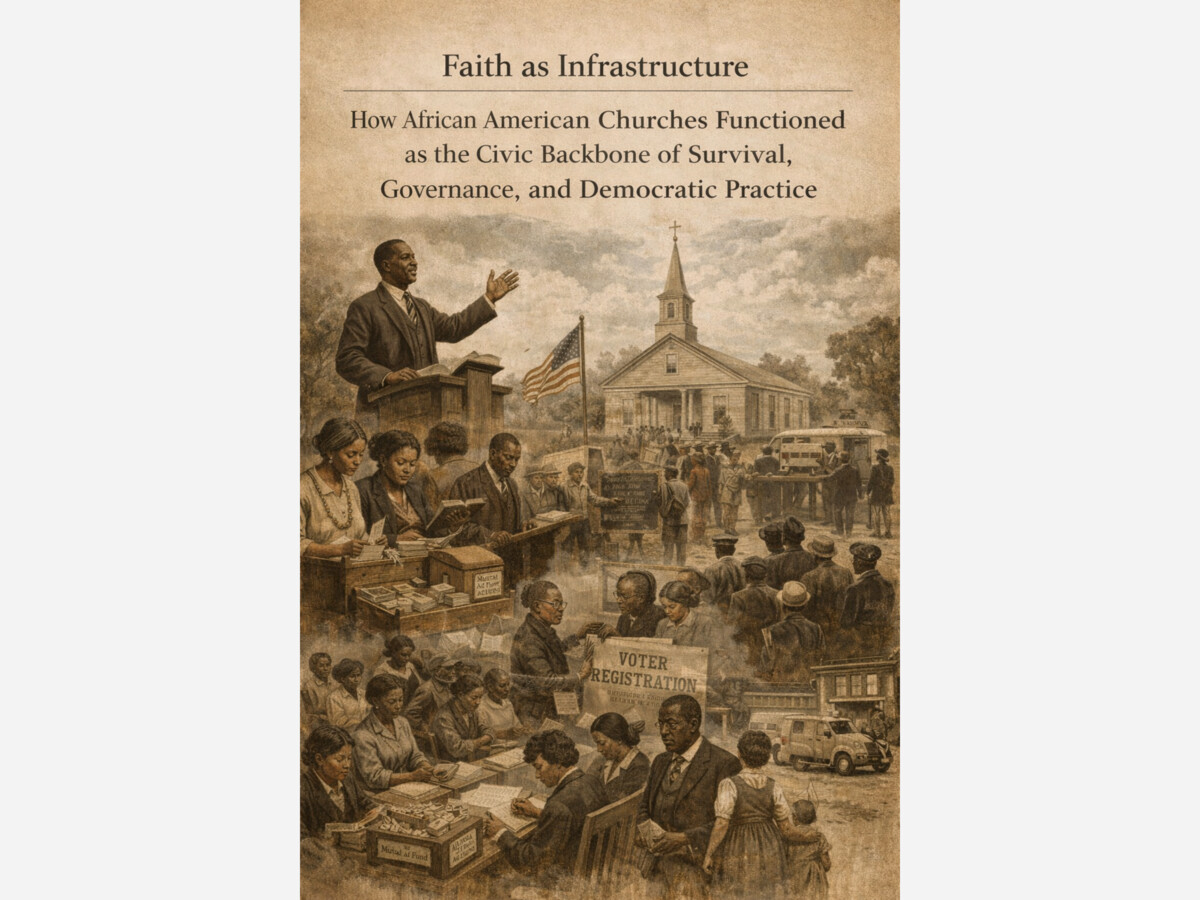

In American history, faith is often framed as belief. For African Americans, faith functioned as infrastructure.

From the earliest days of enslavement through emancipation and well into the twentieth century, African American churches were not merely places of worship. They were systems of governance, education, economic coordination, political organization, and communal protection. In a nation that denied African Americans stable access to law, capital, and representation, the church became the most durable public institution available to them.

This role was not symbolic. It was structural.

Enslavement did not simply exploit labor. It dismantled family structures, denied legal personhood, and criminalized autonomy. After emancipation, freedom arrived without protection. Formerly enslaved people faced violence, economic coercion, and exclusion from public institutions that defined citizenship.

The state did not provide schools, welfare, legal defense, or political inclusion at scale. In many regions, it actively undermined African American advancement.

Into this vacuum stepped the church.

African American churches emerged as the first stable institutions controlled by African Americans themselves. They offered continuity where the state offered uncertainty.

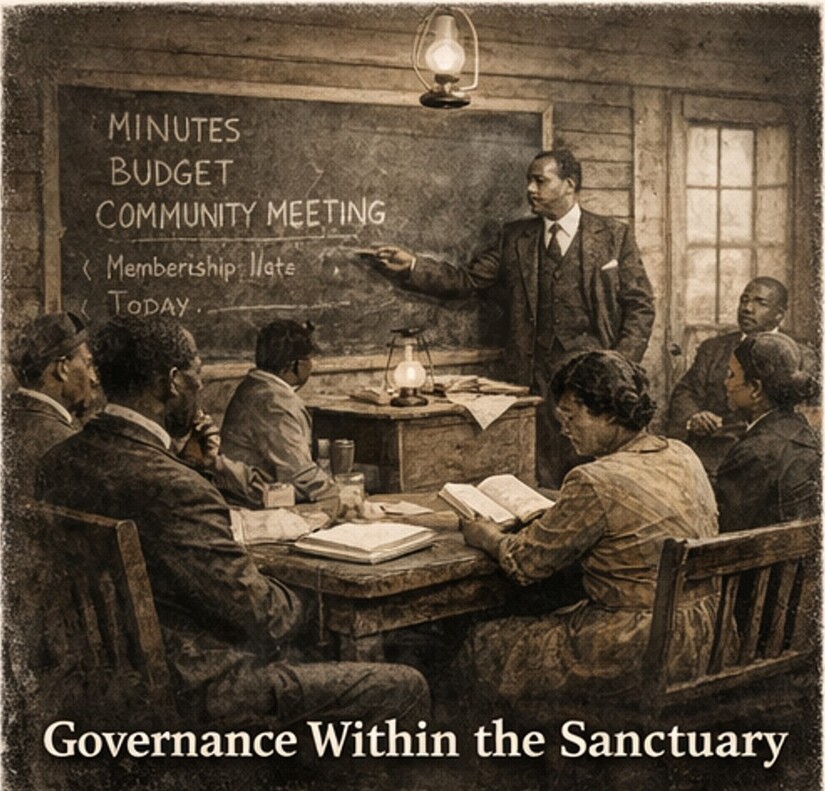

Church governance mirrored and often exceeded democratic practice found in public institutions of the era.

Congregations drafted constitutions, adopted bylaws, elected officers, managed budgets, recorded minutes, and enforced accountability. Members debated policy, resolved disputes, and voted on leadership. Transparency mattered because survival depended on trust.

These practices were not incidental. They trained generations in civic participation at a time when voting rights were restricted or violently suppressed.

Long before African Americans were reliably allowed to vote in public elections, they were practicing democracy every week.

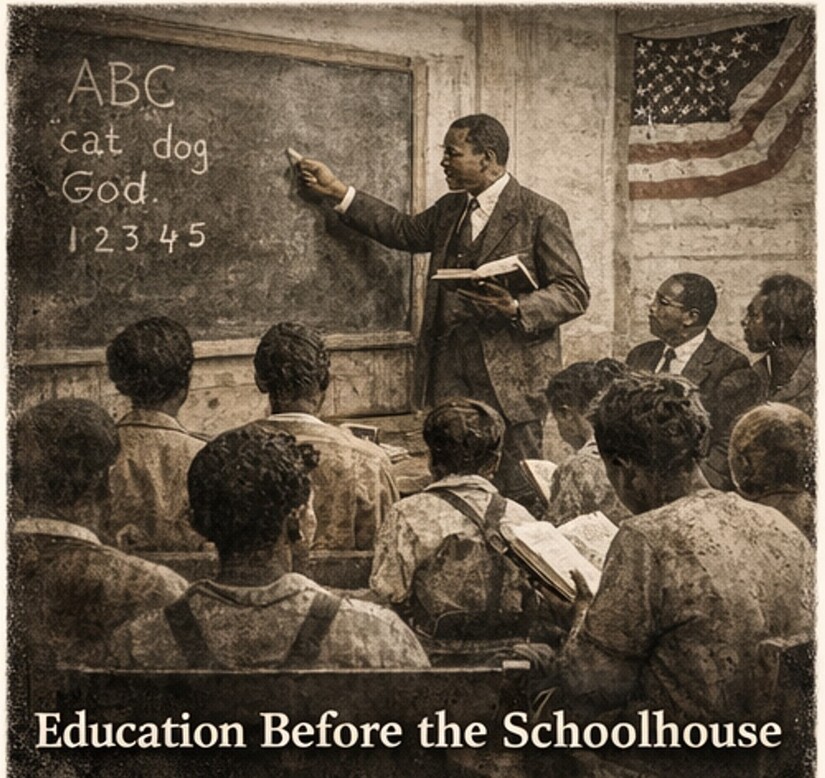

Churches were among the first sites of African American education. Literacy had been criminalized under slavery. After emancipation, churches organized classes, hired teachers, and hosted schools.

Sunday schools taught reading, writing, and arithmetic alongside scripture. Weekday classes prepared children and adults to navigate contracts, newspapers, and civic life. Education was treated as a collective responsibility rather than an individual privilege.

When public schools excluded African American students or provided inferior instruction, churches filled the gap. When school buildings were burned or defunded, instruction continued inside sanctuaries.

Education within the church was not supplementary. It was foundational.

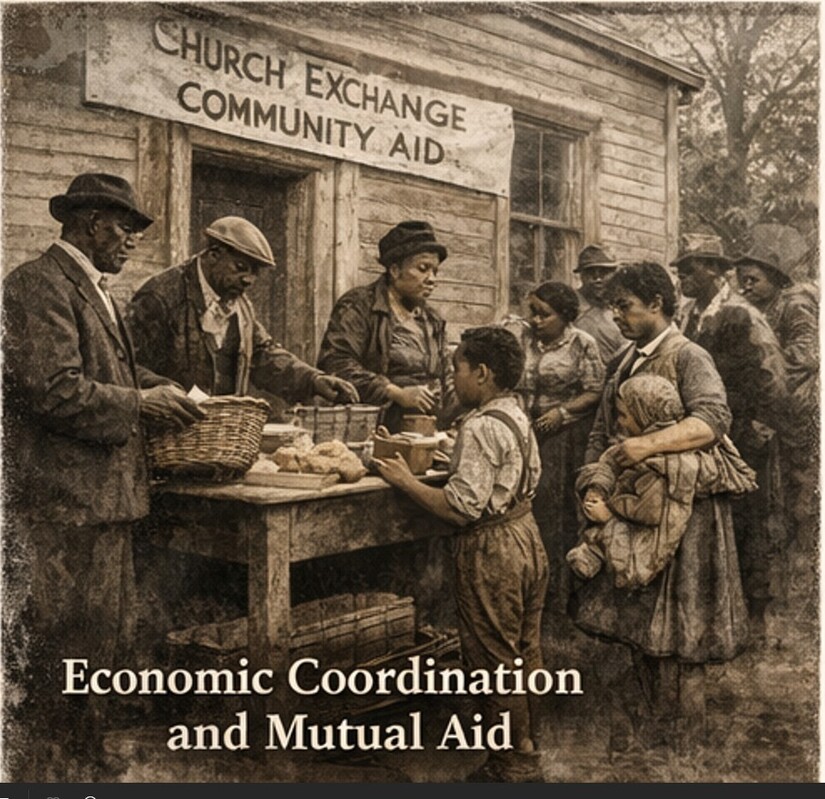

African American churches functioned as economic hubs in communities excluded from formal financial systems.

Congregations collected dues, organized savings, and distributed aid during illness, unemployment, and death. Burial societies ensured dignity in death when insurance was unavailable. Emergency funds stabilized families during crises.

Churches facilitated employment networks, connecting workers with opportunities and sheltering those displaced by violence or economic instability.

This was not charity. It was economic coordination in the absence of state support.

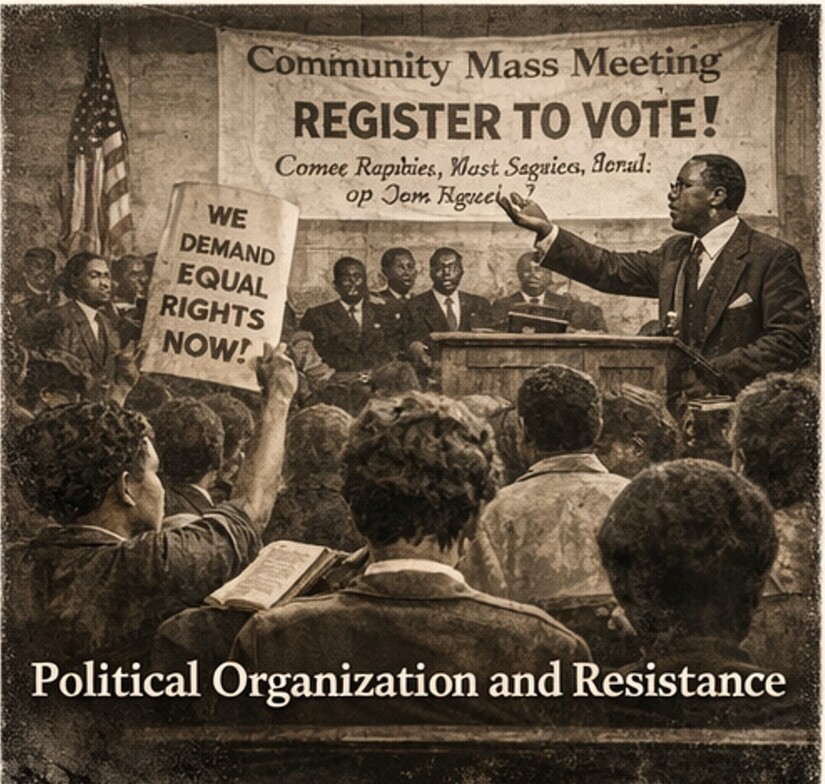

Churches served as the primary organizing centers for political action.

They hosted mass meetings, strategy sessions, and voter education efforts. Ministers often acted as intermediaries between African American communities and hostile authorities. Pulpits became platforms for civic instruction and moral argument.

During the civil rights movement, churches provided logistical infrastructure for boycotts, marches, and legal challenges. They offered meeting space, communication networks, and moral legitimacy.

This political role did not emerge suddenly in the twentieth century. It was built over generations of institutional practice.

In a society structured by racial violence, churches offered relative safety.

They provided physical spaces where African Americans could gather without constant surveillance. They offered emotional refuge from daily indignities and existential threats. Faith communities cultivated resilience in the face of terror that the law either tolerated or enforced.

Spiritual language articulated suffering in a way that preserved dignity. It framed endurance not as submission, but as preparation.

The church did not deny reality. It contextualized it.

African American churches produced leaders who would later shape public life.

Ministers developed skills in public speaking, negotiation, administration, and conflict resolution. Lay leaders managed finances, coordinated programs, and organized collective action. These skills transferred directly into civic and political leadership when opportunities emerged.

Many early African American legislators, organizers, educators, and journalists were trained within church structures long before entering formal institutions.

The church was not a retreat from public life. It was a training ground.

The civic role of African American churches complicates dominant narratives.

It challenges the assumption that African Americans were politically passive or institutionally dependent. It reveals that democratic practice thrived in parallel to the state, often with greater accountability and participation.

Acknowledging this history requires confronting an uncomfortable reality. African American communities often governed themselves more effectively than the governments that excluded them.

Minimizing the church’s role preserves the myth that civic capacity was absent rather than obstructed.

African American churches continue to function as civic infrastructure today.

They provide social services, host community forums, support education, and mobilize political participation. Their influence extends beyond religious practice into public life.

Yet their historical role is often reduced to spirituality alone, stripped of its civic significance.

This reduction is another form of erasure.

Faith as infrastructure is not a metaphor. It is a historical fact.

African American churches did not merely comfort communities denied justice. They organized survival, taught governance, coordinated resources, and sustained democratic practice under conditions of exclusion.

They were not ancillary to American democracy. They were among its most consistent practitioners.

To tell this history accurately is not to elevate faith above critique. It is to recognize infrastructure where it existed and agency where it was exercised.

The American democratic record is incomplete without acknowledging the sanctuaries where citizenship was practiced long before it was legally protected.

This is not religious history alone.

It is civic history.